Beware Google shareholders: The company is losing its voice of reason

“He certainly joined us at an interesting time.” That was how Google’s then-CEO Eric Schmidt introduced Patrick Pichette on his first quarterly earnings call as the tech giant’s new CFO. The former consultant and telecom exec joined Google as finance chief in August 2008, just as the global economy was about to slip into the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

“He certainly joined us at an interesting time.” That was how Google’s then-CEO Eric Schmidt introduced Patrick Pichette on his first quarterly earnings call as the tech giant’s new CFO. The former consultant and telecom exec joined Google as finance chief in August 2008, just as the global economy was about to slip into the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

Under Pichette’s watch, Google got more disciplined on costs, as you would expect when a new CFO is tapped to steer a firm through turbulent times. The company is “very responsible in managing its cost base to make sure that we are adapting to the environment in which we are operating,” Pichette said on that first call back in October of 2008, sticking to the traditional CFO script.

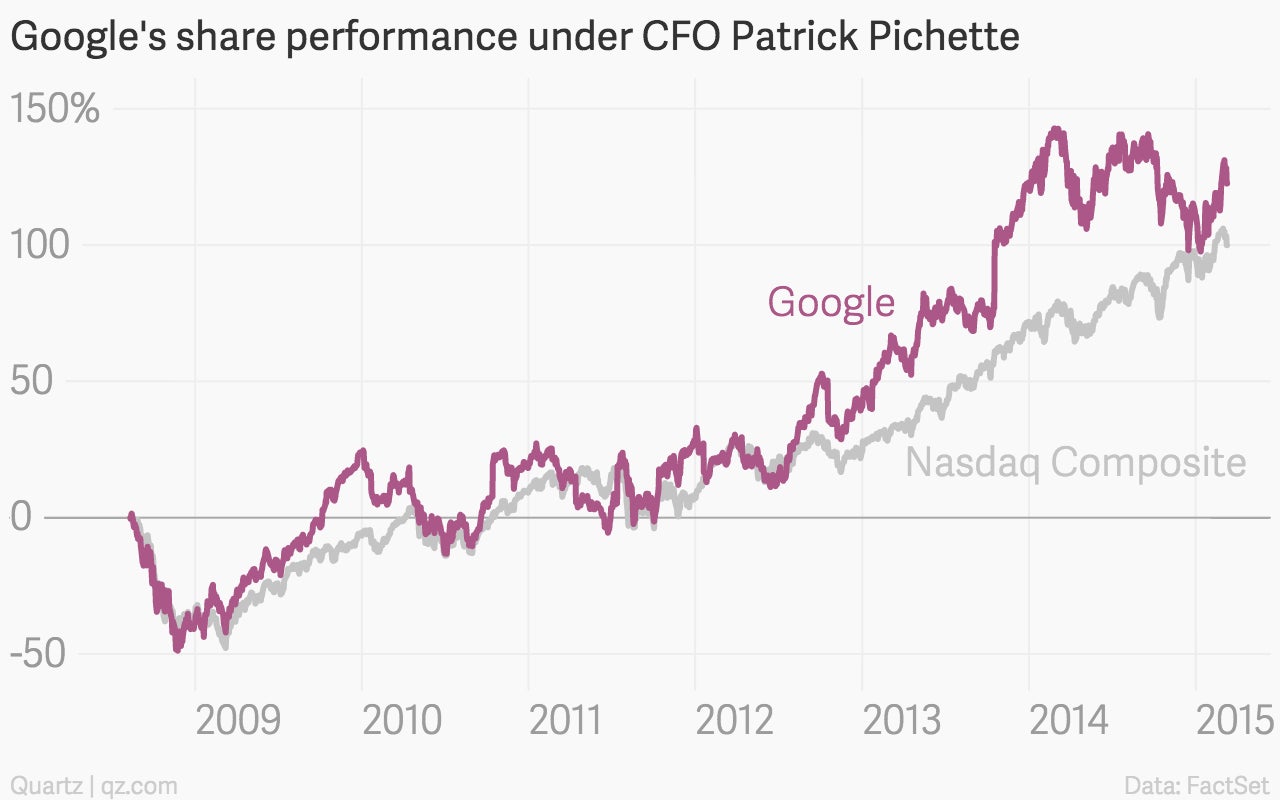

During Pichette’s reign as finance chief, Google’s shares have more than doubled, and outperformed the broader market, so it might make shareholders nervous to learn that the finance chief is leaving the company as soon as a replacement is found.

Even after nearly seven years as CFO, every quarter Pichette goes over ground that other CFOs would take for granted. Earlier this year, for example, he assured investors that the “share price does matter” to company executives. But at a company where the co-founders are adamant about keeping majority control of voting rights regardless of their actual shareholdings, this isn’t something that investors can take for granted.

Fears have mounted recently about Google’s ability to defend its core search operations without getting distracted or wasting money on flashy new ventures. For Pichette, that means fielding lots of questions from analysts and investors about the rationale of investing in self-driving cars, mobile internet delivered by high-altitude balloons, and lavish new corporate campuses. In many ways, his job has been to emphasize what Google will not do as much as what it will.

Prudent and responsible

Pichette did not necessarily fit the traditional CFO stereotype of a humorless, hard-nosed cost-cutter—he once said that the ultimate key to the company’s success was to make “wonderful products that are magical.” But he also made it clear—frequently and consistently—that this would not come at any cost.

Six months into his time at Google, Pichette stressed the need for the company to be “prudent and responsible” on costs. Six years later, the message is much the same. When the company put its Glass project on ice earlier this year, the CFO cited it as an example of the company’s spending restraint on a January conference call:

In those situations where projects don’t have the impact we had hoped for, we do take the tough calls. We make the decision to cancel them, and you’ve seen us do this time and time again.

In April last year, the CFO described the company’s investment-approval process like this:

We continue to always have the business case in mind that says, hey, here’s why this continues to make sense to fund and invest, and with a [return on invested capital] or value in mind for the long-term. But in the short-term, it’s really kind of delivery of milestones on very specific engineering objectives that actually gives them the next round of funding … I mean it’s not rocket science, it just requires a lot of discipline on our part.

But perhaps the message didn’t get through, because in July Pichette said more or less the same thing, but in terms more suited to a Silicon Valley audience:

As I’ve explained many times before, we set up our governance like a [venture capital] model, where we actually have gating and funding. And projects that are more software-based will have much shorter lifetimes before we expect a bunch of returns. Projects that are much more fundamental physics R&D will have much longer timelines for actually funding and expected milestones. But, in both cases, they’re all set around the boundaries of you have a business case, you have a thesis, and that thesis is basically tested on a regular basis through the gating of the funding that they get.

And so it goes. Of course, Google’s investment discipline won’t completely disappear when Pichette leaves the company. But his successor will be very closely scrutinized by investors.