George Washington was the last US president to face an all-out foreign policy uprising

Turns out there’s a close precedent for the spectacle of a poisonously contrary opposing party urging Americans and foreigners alike to ignore the sitting US president. But we must reach back all the way to George Washington and the 1790s, says a leading scholar.

Turns out there’s a close precedent for the spectacle of a poisonously contrary opposing party urging Americans and foreigners alike to ignore the sitting US president. But we must reach back all the way to George Washington and the 1790s, says a leading scholar.

In his day, Washington was branded senile by his opponents—the precursors to today’s Democrats but back then called Republicans—one of whom wished for his early death, according to Joseph Ellis, a Pulitzer Prize-winning US revolutionary-era scholar. Calling Washington a traitor, the Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, tried to defund a treaty he had negotiated with the British.

“To the degree that the current right-wing Republicans don’t think that Obama represents the best interests of the country, they felt the same way about Washington,” Ellis tells Quartz. “The lunacies that we see are not unprecedented. They were there at the creation.”

First, let’s discuss contemporary politics

Today’s Republicans have been in a fairly regular lather almost since Barack Obama was elected president, casting doubt on his legitimacy and generally working to lock him in a full nelson. But over the past two weeks, they’ve gone into a higher state of agitation, into something resembling open rebellion.

On March 4, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell urged governors of the 50 states to defy expected new federal rules governing carbon emissions from power plants, rules that in his view are illegal.

The day before that, House of Representatives speaker John Boehner hosted Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu for a big speech. Obama had opposed Netanyahu’s appearance because it was staged to undercut advanced nuclear negotiations under way with Iran. But, in one of history’s strangest episodes of diplomatic sabotage, it went ahead anyway: House and Senate Republicans, plus some Democrats, cheered as Netanyahu, facing a close election at home, suggested that Obama is a naïve foreign policy actor.

In the latest event, 47 Republicans on March 9 signed an open letter to Iran’s leadership: Tehran could conclude any nuclear deal it wanted with Obama, but Congress would have to approve it, and “the next president could revoke” it, the signees said. The letter appears not to have violated the Logan Act, which bars unauthorized people from conducting negotiations on behalf of the US, a role relegated solely to the president, but some legal scholars say it came close.

Aaron David Miller, a presidential scholar at the Wilson Center, a Washington think tank, says both the invitation to Netanyahu and the Republican letter are unprecedented. Other experts and commentators have said the same—that the president’s right to conduct foreign policy has never been so infringed. “Together they demonstrate that while politics really never stopped at the water’s edge, these days those domestic politics are way off shore,” Miller tells Quartz.

But that ignores the father of the nation

Perhaps no modern president has faced such a revolt, but Ellis points out that Washington confronted—and defeated—a similar uprising.

The issue back then was a diplomatic accord with Britain that came to be called the Jay Treaty. Negotiated just a few years after the cessation of the Revolutionary War, a time when emotions remained brittle between Britain and its former American colonies, the treaty, Washington argued, was nonetheless necessary if the US was to get onto its feet and not disintegrate.

But Jefferson and his political allies wanted the young country to enter a commercially hostile posture with Britain, and instead maintain its cozy relationship with the French.

Washington proceeded, peacefully settling outstanding issues from the Revolutionary War, including extricating residual British troops from present-day Ohio and neighboring states, and ushering in a decade and a half of normal trade between the former combatants.

So began the open warfare among the founding fathers. James Monroe, a Jefferson acolyte (and future president) who was then US ambassador to France, openly told Parisians they could ignore Washington—arguing that he was not the United States’ legitimate leader. Washington summarily fired Monroe. Another Jeffersonian aide behaved similarly, and Washington sacked him, too.

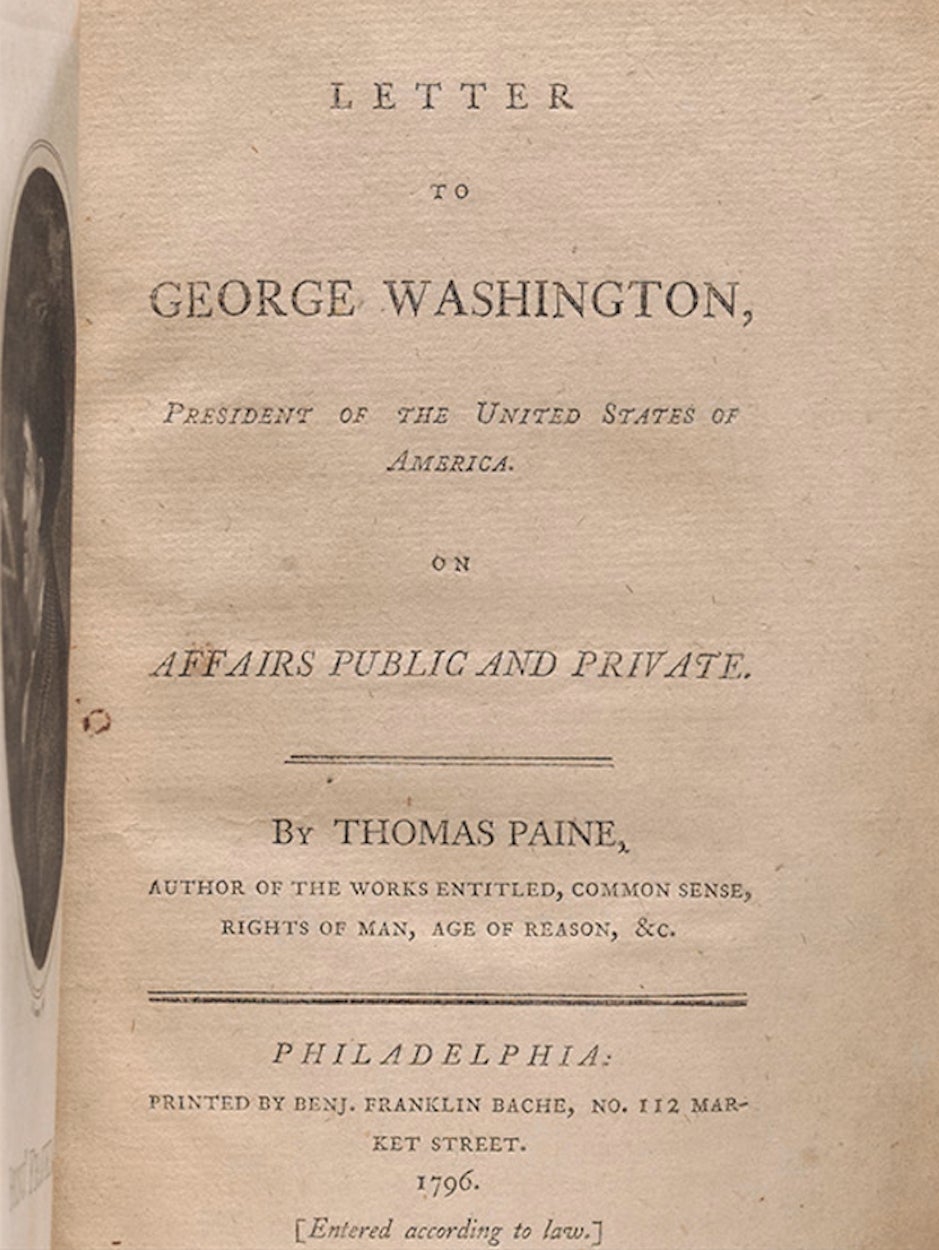

The rhetoric became shrill. Jefferson called Washington senile. A grandson of Benjamin Franklin—Benjamin Franklin Bache—charged that Washington was a traitor, who had collaborated with the British in the war. Tom Paine wrote an open letter (left) in which he prayed for Washington’s imminent death, Ellis said.

To withhold Senate approval of the treaty, Jefferson and his acolytes fired up the public into an anti-British frenzy. Washington out-maneuvered them and won Senate ratification, at which point the Republicans shifted the field of battle to the House of Representatives, where they attempted to deny funding to put the treaty into effect. Washington won that, too, by a close, 51-48 vote.

Ultimately, Jefferson abided by the treaty when he himself became president in 1801. But the die for no-holds-barred partisan politics was cast.