$1.5 million for 500 square feet: Is Hong Kong heading for a crash, or will shoebox homes just get smaller?

The International Monetary Fund has given Hong Kong bank shareholders a fright today by issuing a warning that the Chinese territory faces a real estate slowdown that poses risks for banks. After a long run-up in real estate values, a correction is upon us, the IMF stated in its report dated Nov. 17 but published today.

The International Monetary Fund has given Hong Kong bank shareholders a fright today by issuing a warning that the Chinese territory faces a real estate slowdown that poses risks for banks. After a long run-up in real estate values, a correction is upon us, the IMF stated in its report dated Nov. 17 but published today.

The IMF said the property sector represents half of outstanding loans for use in Hong Kong while real estate is often also used as loan collateral. A sharp property price correction would lead to an “adverse feedback loop between economic activity, bank lending, and the property market,” the IMF explained.

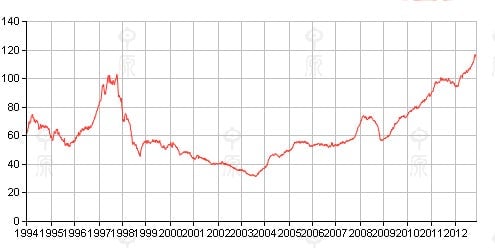

Hong Kong is currently the world’s most expensive place to buy a home. An apartment just sold there for $60 million. The city’s property market is notoriously volatile. Booms and busts are frequent. Locals in the Chinese city often trade apartments as frequently as Americans would trade shares. Property managers sometimes put reports about local transactions and prices over the last quarter in residents’ letterboxes, complete with candlestick graphs showing a dizzying number of sales and purchases. The territory experienced what felt like painful real estate downturns in 1997, in 2003 with the outbreak of SARS (pdf), and in 2008.

But real estate crashes in Hong Kong do not tend to cause bank crises. Locals usually do not default on loans and post the keys back to the bank. That is because, on average, they are not highly leveraged. They tend to take the pain of negative equity stoically, either by doing nothing or working a second job. In 1997, when Hong Kong was mired in the Asian financial crisis and property prices plunged, taxi license applications soared and became a hot investment asset themselves (paywall). So a property bust is “mo fan” (麻煩 Cantonese for pain in the neck), but not scary.

The territory’s citizens are big savers and buy their apartments with sizable deposits. HSBC, Hong Kong’s largest mortgage lender and a bellwether for the Hong Kong banking sector, said in its last interim report that its average loan-to-value ratio on new mortgages was 50% . The loan to value ratio on its entire Hong Kong loan book, which will have been flattered by rising prices, is only 34%.

Back in September 1997, according to a survey released in 1998 by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the mortgage delinquency ratio was just 0.1%. Back then, the average loan to value ratio on mortgages was 52%, which provided enough of a cushion to absorb real estate valuation falls.

A property crash could have big ramifications for Hong Kong retailers and, of course, construction companies. As London consultancy Capital Economics wrote in a note published last month, in the event of a real estate crash: “ consumers would cut back on spending in response to a fall in their wealth.”

They added: “The construction sector is also likely to be badly affected if property prices fall, while there would also be reduced demand for a number of other associated sectors, including estate agents, furniture, and other household goods.”

But the city’s government is unlikely to allow a real estate price correction that could damage property developers or banks. The Hong Kong government tends to aggressively pursue land policies that make sure its property tycoons—such as Asia’s richest man, Li Ka-shing—and its banking system stay healthy.

When land prices fall, Hong Kong restricts new land sales. The overall effect is that Hong Kong’s hard pressed citizens’ homes get smaller and they become increasingly unhappy with their lives. They are often to be seen marching in the streets to protest high home prices. Some of the city’s poor live in so-called “cage homes”, which are 6-foot-by-2-foot boxes in slum areas. But real estate developers fare okay.

New apartments developed in Hong Kong for middle-class buyers have earned the nickname “shoebox homes.”

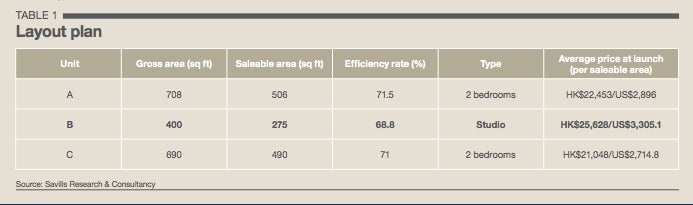

Courtesy of Real Estate consultancy Savills, here is a chart of a typical new apartment development in Hong Kong. A two-bedroom, 506 square-foot unit that would probably house a family of three (or one wealthy person) is offered at $2,896 per (so-called saleable) square foot, a total price of just under $1.5 million.

Not allowing a house price crash will harm Hong Kong in the long run, as independent economist Andy Xie points out here. He says that the city has been squeezing land supply for over a decade. In Xie’s words, policies that keep property prices inflated, for the benefit of banks and developers, hurt the city overall, because:

The social cost of squeezing [land] supply to support a high price could precipitate social turmoil. While Hong Kong is considered a high-income economy, numerous families, many with members of three generations, live in one room. More than two-thirds of Hong Kong’s land is undeveloped. And reclamation, the main source of new land for Singapore, has potential in Hong Kong. So, while popular perception attributes high property prices to a land shortage, it is utterly untrue. Hong Kong’s elite fuels this misperception because they want to keep people in the dark.

Hong Kong probably isn’t heading towards a banking crisis, then. But it may be on the edge of a social crisis. Hong Kong policymakers might simply react to the IMF’s warning with new plans to restrict land supply. That could ensure that people’s homes, instead of getting cheaper, just get smaller.