China is about to stop making savers subsidize wasteful state companies

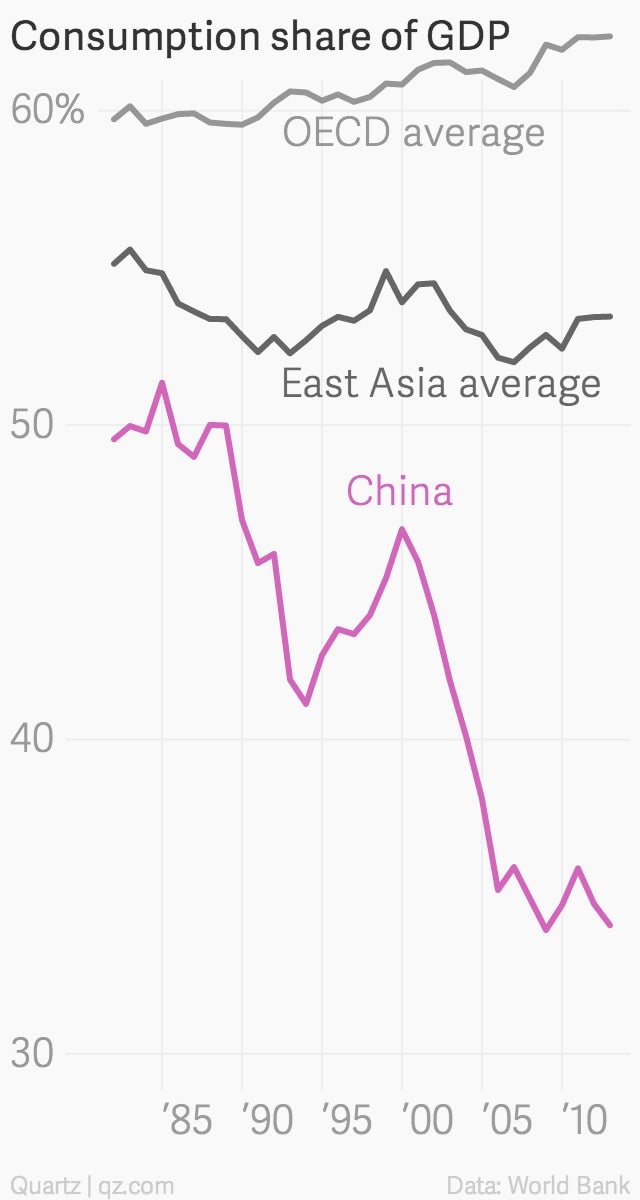

For many Chinese, their country’s “miracle growth” hasn’t felt quite so miraculous. Because the government sets deposit rates artificially low—lower, usually, than inflation—Chinese have actually lost money on their savings most years. Though this discourages people from spending—China’s household consumption is woefully low—that hasn’t mattered to the government. Those ultra-cheap savings let state-owned banks lend favorably to companies, many of them also state-owned—in effect, shifting savers’ would-be wealth to the state instead.

For many Chinese, their country’s “miracle growth” hasn’t felt quite so miraculous. Because the government sets deposit rates artificially low—lower, usually, than inflation—Chinese have actually lost money on their savings most years. Though this discourages people from spending—China’s household consumption is woefully low—that hasn’t mattered to the government. Those ultra-cheap savings let state-owned banks lend favorably to companies, many of them also state-owned—in effect, shifting savers’ would-be wealth to the state instead.

Well, that’s about to change. China’s top central banker, Zhou Xiaochuan, just announced that the “probability is very high” that the government will lift the cap on deposit rates this year. Expect deposit insurance, a prerequisite for the liberalization, in the first half of 2015, said Zhou.

This has long been regarded as critical to containing the country’s debt woes and helping China “rebalance” toward a sustainable growth model.

But it might be too late to make much of a difference, says Capital Economics.

A few years ago, it would have had a huge impact. Letting deposit rates rise in accordance with demand would means households would earn a return on their savings, making them feel wealthier and, thereby, spurring spending.

It also would have helped rein in wasteful investment. By making loans cheap, the rigged deposit rate encouraged companies to invest without much thought about future cash flow, and let banks neglect risk management. China’s post-global financial crisis credit bonanza exacerbated this, swelling its debt burden to more than 280% of its GDP, up from about 150% of GDP in 2008, according to a recent McKinsey report.

But in the intervening years, something changed—and in a weird way, the market liberalized on its own.

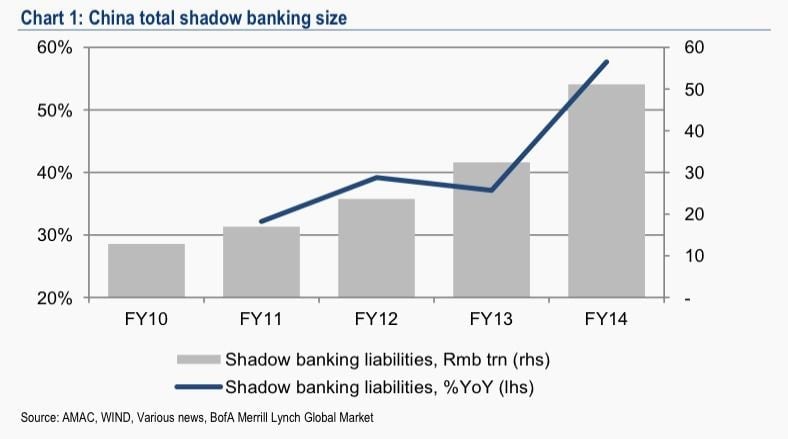

As China’s economy slowed, firms—particularly local governments and their pet companies—became more and more desperate for cash, their investments having been tied up in long-term projects or frittered away. To keep liquid, they borrowed from the shadow market, off the balance sheets of banks—often at nosebleed rates of 15-20%. To fund this profitable trade, banks began selling wealth management products (WMPs) to their banking customers, effectively securitizing those shadow loans. Since WMPs offered much higher returns than deposits, savers plowed their money into them. These risky loans now total 51.2 trillion yuan ($8.2 trillion), according to Bank of America/Merrill Lynch.

WMP-buyers seldom knew what they were investing in—but then, why would they care? So far, local governments or some nameless entity have bailed out all the WMPs that have neared default (at least, as far as has been made public). The notion that the government won’t countenance a default is commonly known as the ”implicit guarantee.”

And this, ladies and gentlemen, is what saps Zhou’s promised deposit-rate reform of the curative power it once might have had.

Until the government removes its implicit guarantee—something it’s just now starting to work on—state companies will still be less risky to lend to than to private firms, says Capital Economics, even though the latter are much more profitable. And that means finally lifting that deposit rate probably won’t do much to curb wasteful investment and loony lending.