The real moral of “Cinderella” that everyone’s missing

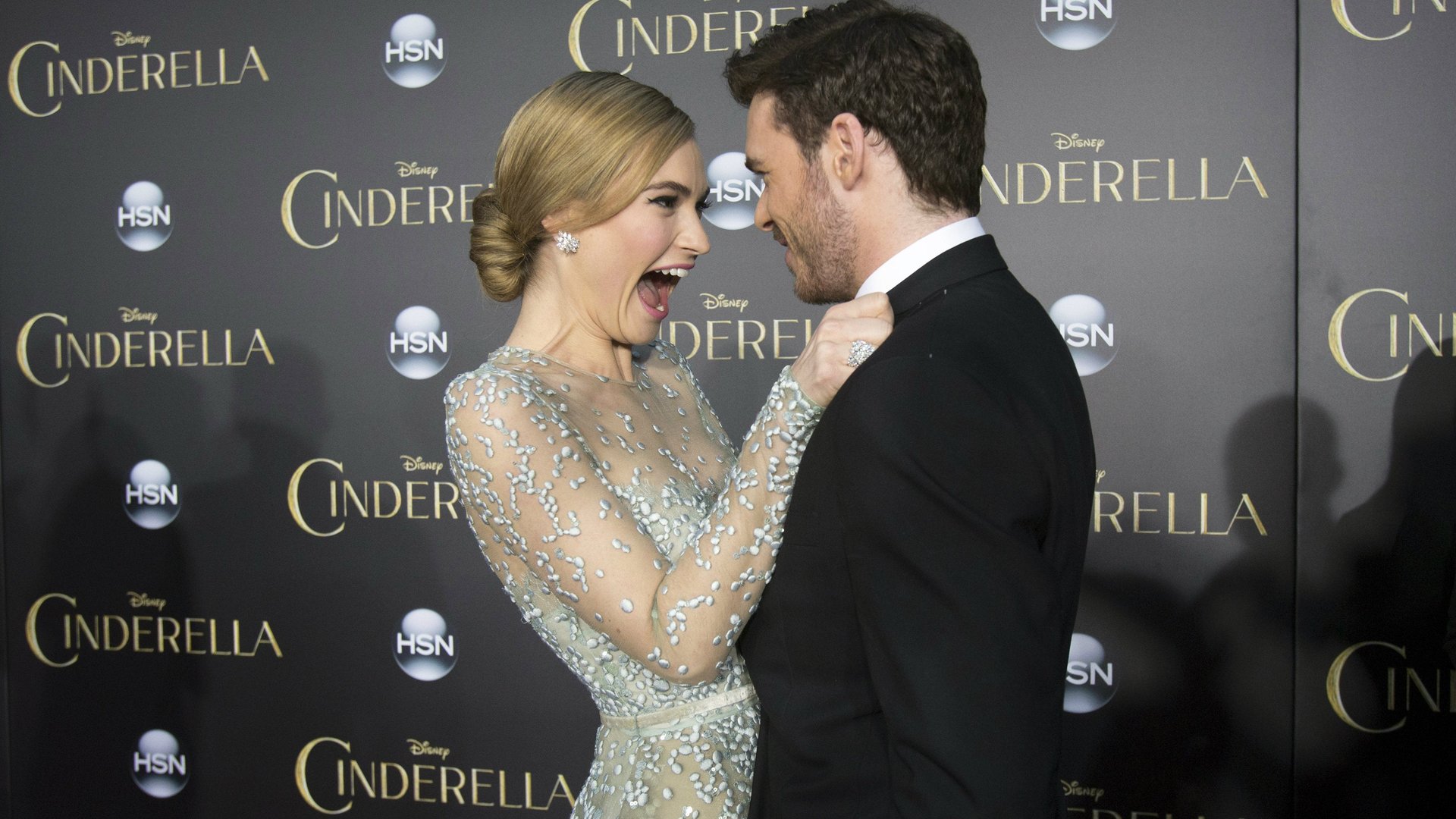

Disney has just released a live-action version of Cinderella, a retread of the beloved 1950s animated classic, complete with poofy gowns, glass slippers, anthropomorphic mice, and a magic pumpkin. This version of the fairy tale, based largely upon Charles Perrault’s 1697 publication of Cendrillion, has so permeated our culture that virtually everybody in America, be they male, female, young or old, is familiar with the story. It’s little wonder that the tale is so popular, since we all like a rags-to-riches narrative, and, as Mickey and Minnie Mouse have amply proven, we like anthropomorphic mice too.

Disney has just released a live-action version of Cinderella, a retread of the beloved 1950s animated classic, complete with poofy gowns, glass slippers, anthropomorphic mice, and a magic pumpkin. This version of the fairy tale, based largely upon Charles Perrault’s 1697 publication of Cendrillion, has so permeated our culture that virtually everybody in America, be they male, female, young or old, is familiar with the story. It’s little wonder that the tale is so popular, since we all like a rags-to-riches narrative, and, as Mickey and Minnie Mouse have amply proven, we like anthropomorphic mice too.

When Perrault wrote his fairy tales, he included the morals of the stories at the end, so that readers could more easily absorb the messages that he was attempting to convey in his writing. The explicit morals fell away in English translations, but those and other messages remain, locked in the narrative, some of which may not be healthy for our modern society to embrace. For instance, marriage should probably not be seen as a solution to life’s problems. Also, children should not be taught that martyrdom and kindness will lead to riches and a meteoric rise in social status since sadly, nice people don’t often come out on top. While these messages are problematic for our youth, however, there is another message embedded in the Cinderella story that is more harmful still.

You may be thinking, “I know where this is going. The most disturbing moral of the fairy tale is that physical beauty has paramount importance.” That is indeed a troubling message, but it is not the most harmful. First, it happens to be true. Our society does value and reward physical beauty. Second, most children have already figured that out by the time they are exposed to Cinderella. Regrettably, teachers, peers and even parents favor attractive girls and boys over unattractive ones.

No, the message from Cinderella that is most corrosive for our society is that marriage leads to happily-ever-after. Young children, girls in particular, are encouraged to think of their wedding day as the ultimate event in their life stories. Marriage is treated not as just one choice among many choices that are made over the course of a lifetime, but as a supreme accomplishment, a brass ring that must be grasped. The romantic story begins with a first date and progresses through a series of milestones that are easy and fun to document on Facebook: We’re in love! Check out the diamond ring! Save the date! Finally, there are beautiful photos of The Big Day itself, complete with princess gown.

After the honeymoon is over, the couple is expected to live happily ever after. Unfortunately, for the protagonists of the story, life is not transformed by stepping through the magical wedding portal. Worries, disappointments and uncertainties loom just as large as before the wedding, and the roadmap provided by society, the one with milestones like dating, diamonds and bachelor parties, has come to an end. Newlyweds may feel like explorers who have arrived at the edge of the known world, beyond which the map only indicates, “There be dragons.”

Close to half of American marriages end in divorce, and of the ones that last until death, it’s a pretty safe bet that not all of them are happy. On top of that, many Americans never marry at all. That means that any child watching the new Cinderella movie this week has far less than 50-50 odds of spending his or her entire adulthood in a happy marriage. Or, to put it another way, most of our children have no shot at the Cinderella version of happily-ever-after.

Because many of us want so badly to believe in happily-ever-after, we may be tempted to tell our children that they can achieve the brass ring of a lifelong happy marriage if they just try hard enough. That is disingenuous. While marriage does take work, most people who suffer in their marriages are not lazy, and most people who remain single, choose divorce or are abandoned by their spouses are not too apathetic to seize the happiness that could be theirs. Human relationships are complex and fraught with unpredictable emotions, incompatible personality traits, evolving life goals, hardships of all kinds. The best we can hope for our children is that they enter into relationships that bring them, on balance, more joy than pain.

Given that most children cannot look forward to a lifelong happy marriage, what can we, as a society, do to prepare them better? We can start by telling them that marriage should not be life’s greatest ambition, that it’s not a solution to life’s problems, and that they aren’t failures if they don’t achieve happily-ever-after. Instead of talking about fairy tale weddings, we can talk about what it takes to have fulfilling, constructive relationships with other people. We can tell them that while happiness can come from marriage, it can also come from many other relationships and experiences, and that one of the best predictors of happiness is the amount of time that people spend with family and friends. Most importantly, those of us who are well beyond the honeymoon phase of marriage can open up to younger people about the confusion, disappointments and challenges that persist or arise after the wedding guests have gone home. If we don’t tell them, Disney certainly won’t.

When Perrault wrote his version of Cinderella, he said that the most important moral of the story is that no endowment can guarantee success and happiness, and that sometimes a godparent, a member of society who has committed to care for someone outside his or her own family, needs to get involved. We are all the godparents of America’s children. It’s up to us to teach younger generations that happiness is more complicated that saying, “I do” and support them as they find their way beyond the inadequate roadmap that we have, until now, been handing them.