Big fairs like Art Basel Hong Kong are great for business, but bad for art

HONG KONG—You were out of luck if you wanted to find a hotel room in Hong Kong this weekend. Art Basel Hong Kong opened on Friday the 13th, and a large chunk of the global art world descended on the city.

HONG KONG—You were out of luck if you wanted to find a hotel room in Hong Kong this weekend. Art Basel Hong Kong opened on Friday the 13th, and a large chunk of the global art world descended on the city.

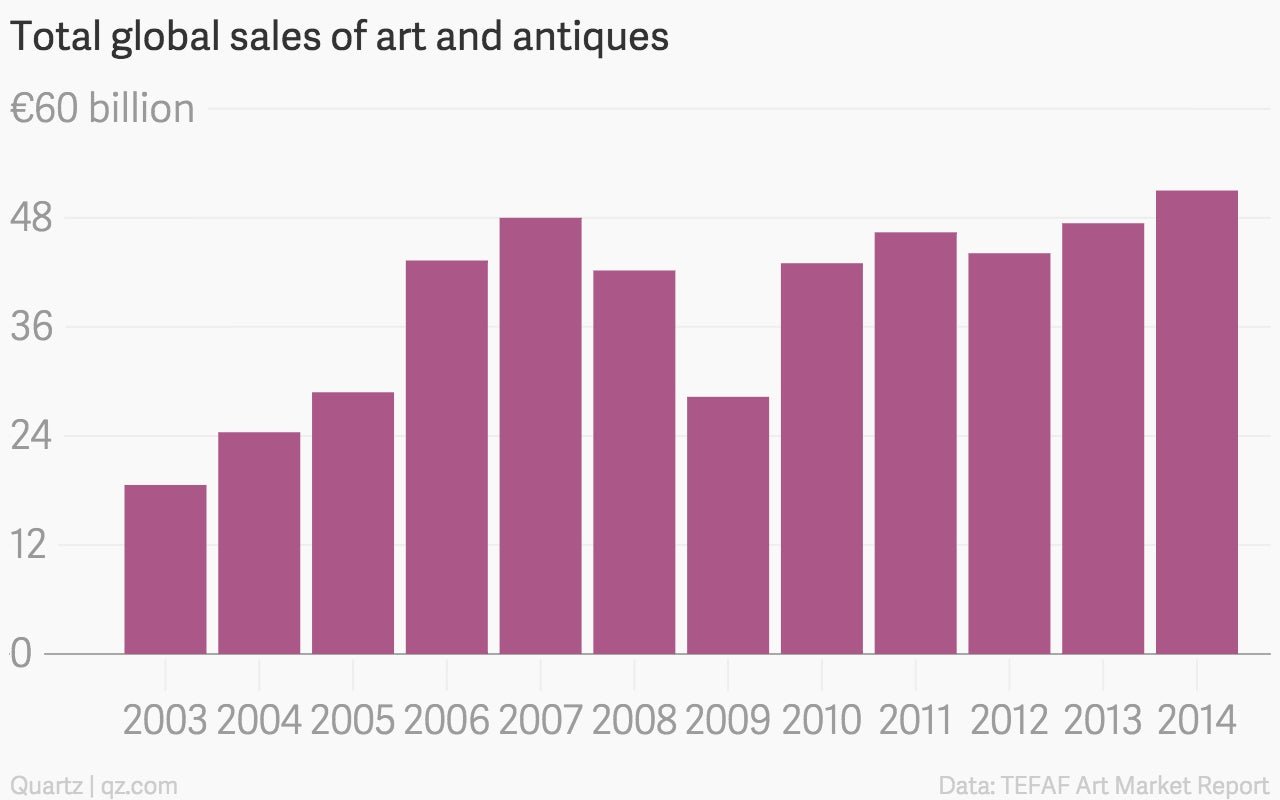

Art Basel is Asia’s largest art fair, but it has plenty of competition around the world. There are now 180 major international art fairs held annually, accounting for over €10 billion ($10.5 billion) in sales. The top tier of the art fairs, about a fifth of the overall total, together bring in over a million visitors a year, and helped drive the overall art market to record sales of €51 billion in 2014.

Collecting art, once a fairly esoteric pursuit, has become the norm for the global 1%, and the fairs that attract the big spenders are a legitimate industry unto themselves. These top-shelf fairs bring a flood of rich and well-known visitors wherever they land—this year collector Ulli Sigg, Tate director Nicholas Serota, actress Susan Sarandon, and Alibaba founder Jack Ma were among the VIP attendees in Hong Kong.

On opening night, guests at the VIP lounge sipped on Brandy Warhols: cocktails served in Campbell’s soup “cans,” with Andy Warhol’s famous prints on the wall behind them, part of the collection of art fair sponsor UBS. About $3 billion in art could be sold by the time the fair closes March 17, insurer Axa estimates.

Not much room for contemplation

The rapidly-growing art fair industry is great for fair owners and for the business of buying and selling art. But money-making aside, what is it doing to art itself?

At its best, art is a portal to a contemplative space. Like all the arts, the visual arts respond to our innate, relentless search for meaning. Art can lift us out of our egotistical, self-centered, often jaded view of the world to offer us a new way of looking, and of questioning our reality. But any space for that sort of existential contemplation is pretty much non-existent at the world’s big art fairs.

The operative word for most people associated with these fairs is frustration. As one collector told me: “It’s like being given this huge buffet banquet and being told ‘you have two minutes—eat all you want.'”

Serious collectors despair as their conversations with artists are interrupted by fair visitors with networking agendas, or by even more important collectors (you can assess your station in life by what time your VIP pass allows you entry to an art fair on opening day). Gallery owners still jet-lagged from the last art fair are more stressed about recouping astronomical booth costs—which at fairs like Art Basel can be over $60,000—than they are about offering viewers a meaningful experience.

The end of connoisseurship?

One London gallery owner who represents several critically and commercially successful artists likes to grumble that the rise of art fairs means the end of connoisseurship. “The reason I am in the art business to begin with is because I love art,” he told me. He loves speaking to artists and the collectors who want to really understand the work. Art fairs, though, are his least favorite part of the job—and they are what he and most gallery owners have to spend more time doing.

Artists under pressure from galleries have to put the work they really want to do to on a back burner and produce something that will have a greater chance of selling. While they appreciate the international exposure fairs give them, many are unhappy with viewing conditions. “My work consists of long term projects, and the fleeting nature of the art fair is not conducive to the kind of engagement that I and other artists rely on to sustain our practices,” said a rising artist who has a solo show at this weekend’s Art Basel in Hong Kong.

What’s worse, art fairs are actually helping move art out of the public eye. With financial markets and tax havens becoming more regulated, the 1% is increasingly relying on art and art fairs instead to store their cash. Then they stash the art away in a steadily growing number of grim looking art warehouses that blight the European landscape—often in Switzerland, but increasingly also in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Unlike the free entry offered by many museums worldwide, art fair tickets do not come cheap. While the moneyed few get VIP passes and are swooshed through city traffic in official cars, the paying public feel the hit to their wallets, and there are plenty who can’t afford it. Tickets to Hong Kong’s Art Basel started at $30 a day. Often the people who visit just out of an interest in art find their eyes glazing over as they gaze on booths packed with art works in no order, other than that the titles match the price list.

Lars Nittve, director of M+, a contemporary arts museum opening in Hong Kong in 2017, said he appreciates that art fairs are part of the ecosystem, but said their focus on sales detracts from the art itself. “It can spoil the experience to look at art with a price tag. There are things you do not get to see and the original intentions of the artist can be obscured by market values. The price tag is not the reason it is being made.”

Despite all the griping, though, gallery owners and artists know they don’t really have a choice. The market for art is now global and the art fair is the shopfront.

Anita Dawood co-founded the London-based contemporary art organization Green Cardamom in 2004. She now develops and edits visual arts publications.