Mongolia, which has seven times as many goats as people, could grow 20% next year

Mongolia, the vast, landlocked former Soviet satellite in between China and Russia, serves up statistics as eye-popping as its cobalt blue skies and sweeping steppes.

Mongolia, the vast, landlocked former Soviet satellite in between China and Russia, serves up statistics as eye-popping as its cobalt blue skies and sweeping steppes.

The world’s most sparsely populated nation, Mongolia is home to 2.8 million people—and around 20 million goats. It also has extremely vast mineral deposits, yet its people, many of whom are nomadic herders living in tents called “gers,” are desperately poor, with GDP per capita standing at just $3,635.

Still, Mongolia’s economy could skyrocket next year, depending on a lot of fast moving political and financial variables. The World Bank forecasts 16% growth while the Economist’s executive editor, Daniel Franklin, says it could reach 20%. Not so fast, according to a recent New York Times article, which said Mongolia looks “shaky” and that the country’s mining-driven boom is already deflating.

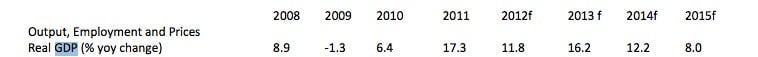

Mongolia’s economy is volatile, as so much of the country’s wealth is pegged to commodities prices. Here is how it has been growing:

Much of what will happen to Mongolia’s economy next year depends on China… on which Mongolia depends for 93% of exports, according to the World Bank. Mongolia’s fortunes are very much linked to those of Chinese furnaces and factories. In recent months, Mongolia’s coal exports slumped “amid China’s decelerating exports,” according to a late November report by the International Monetary Fund. The Beijing government is flinging money into projects designed to keep its economy growing, so that is perhaps not too much of a concern for now. But China is also importing less copper, which is another of Mongolia’s key exports.

…But also on the progress of an increasingly fractious relationship between the government and foreign miners. One mine, a massive copper and gold project named Oyu Tolgoi in the south of the country near China and majority owned by Rio Tinto, is on the verge of starting commercial production. It is so big that, according to Rio, it will account for 33% of Mongolia’s GDP by 2020. If it starts up as planned next year, this will boost economic growth to a one-off, four year high of 16.2% next year, World Bank forecasts show. (Royalties from the project may not flow into tax coffers until around 2016.) But Oyu Tolgoi will only start production if the government and Rio can resolve a dispute over a hefty and well timed proposed tax the government said it wanted to levy on the mine last October.

A new law, passed in May, seemed designed to dissuade foreign investors from entering the mining sector. It forbids them from owning controlling stakes in Mongolian miners and companies in other strategic industries. The legislation was partly aimed at Chinese investors, who own a large chunk of Mongolia’s mining licenses, but also played to wider resentments among poor Mongolians, who complain that foreigners are winning all the spoils of the mining boom.

In September, Chinese state resources giant Chalco ended talks to buy Canadian-owned, Mongolian-based coal miner SouthGobi Resources. SouthGobi’s CEO departed, and operations at its mine, Ovoot Tolgoi, have been suspended since June because the company needs to preserve cash. “The question is, is this economy gearing up for big mines to start producing next year?” says Thomas Holland, head of Asia at hedge fund Cube Capital. A spokesman for Rio Tinto’s Mongolian operations did not return an email seeking comment.

The democratic country’s new government, which came to power in June, is full of resource nationalists who are likely to take an even stronger stance against overseas investment than the last administration. They are playing to a happy crowd. The Economist commented in January that Mongolia was “being dug up and sold to China,” and realizations about this happening have annoyed Mongolians for several years. Over a third of Mongolians live on less than 68 US cents a day, according to charity World Vision. Chinese miners and builders who carry out projects in Mongolia tend to import Chinese workers.

So some Western investors have lost enthusiasm. “People are nervous seeing laws changing. It is becoming more difficult to operate in Mongolia, ” says Holland. Anthony Milewski, a former private equity investor in Mongolia who now runs Australian-listed Quest Petroleum, points out that the government’s plans to levy new taxes on the Oyu Tolgoi project represent an unexpected change in the agreement between Mongolia and the copper mine’s owners.

“The resource nationalism has seriously damaged investor confidence. It will take time and work for investors to regain confidence,” he says. “When you change the rules of the game on a multibillion dollar deal, investors lose trust.”

Wealthy foreigners now need to keep a low profile. A neo-Nazi movement aimed at China sprang up a few years ago. But other foreigners are being attacked. An American fund manager told Quartz, on the basis of anonymity, that early last year local thugs shouted racist insults and attempted to mug him as he walked from the Central Tower mall in Ulaanbaatar’s central Sukhbaatar Square, which houses Louis Vuitton and some smart restaurants, to his waiting chauffeured car.

The government is also mismanaging the economy by enthusiastically building new infrastructure and handing out financial sweeteners in an attempt to hand some benefits of the mining boom to the people. The state’s efforts to help are creating rampant inflation. This World Bank report (pdf) outlines how government cash transfers to poor herders helped lift meat and dairy prices 49% in the year to August as they had less incentive to work or sell livestock. It also reports that prices of construction materials have soared after the government started more new projects than the local industry could cope with. It says government capital expenditures rose 82% in the year to August. But 60% of Mongolians cannot stretch their wages far enough to meet their basic needs.

And Mongolia’s financial system could get shaky. If Chinese demand slows further and if more joint Mongolian-Chinese projects fail the way Chalco’s did, domestic miners may start defaulting on bank loans. “A lot of people are leveraged to continued growth of the mining sector,” says Holland. Non-performing loans at Mongolian banks currently stand at around 4.5% of total loans outstanding, according to figures supplied by the National Statistics Office of Mongolia. According to the World Bank, the bad loans figure rose to 17.4% in 2009, during a banking crisis prompted partly by miners failing to repay loans in response to the global slowdown

There are other worries lurking in the country’s finances. Because the government is spending more than it is making in taxes, the country could record a deficit of 9% of GDP (pdf, p. 9) this year. So Mongolia faces stark choices. The government needs to take some of the wealth foreign miners are generating for the nation—but not by grabbing so quickly at the spoils that projects stall or stop completely. And it needs to lift its people out of poverty—but not through handouts and stimulus projects that are doing more harm than good. Whether the country will manage to strike this tricky balance is less of a question, however, if China slows to the point where it has little demand for its neighbor’s exports anyway.