Why countries that recognize Palestinian statehood turn their backs on Kosovo

When we talk about Islam in Europe, we’re generally thinking about Bangladeshis in Britain and Algerians in France. Maybe Pakistani migrant-farmers in Greece, or Somali refugees in Scandinavia.

When we talk about Islam in Europe, we’re generally thinking about Bangladeshis in Britain and Algerians in France. Maybe Pakistani migrant-farmers in Greece, or Somali refugees in Scandinavia.

But the Muslims of Europe’s Balkan peninsula long predate Maghrebi settlement in the Goutte d’Or. And few outside the region realize that, in fact, there are countries on the European continent where Muslims compose the majority—and not as a result of spectral “reverse colonization.”

Countries with Europe’s most substantial Muslim communities include Bosnia-Herzegovina, where they are 40% of the population, according to the CIA; Macedonia, where they make up a third; Montenegro, where they’re 19%, and Bulgaria, 7.8%.

Nearby Albania and Kosovo are arguably Europe’s “most Islamic” countries, when excluding Turkey. In Albania, 56.7% of the population adheres to Sunni Islam. And although exact numbers aren’t available for Kosovo, one of the world’s youngest countries, estimates of the Muslim population hover at around 90% of its two million residents.

Both countries are home to ethnic-Albanian majorities, many of whom are descended from Christians that converted to Islam during four centuries of Ottoman-Turkish rule. Despite this, a number of Muslim-majority countries refuse to recognize Kosovar statehood; even as they passionately advocate for Palestinian sovereignty with the other hand. Most notable among these are Iran, Syria, and the Palestinian Authority.

“The PLO didn’t recognize the independence of Kosovo,” Imam Stephen Schwartz, executive director of the Center for Islamic Pluralism, tells Quartz. “Kosovo is not a member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. And this is because Kosovars and Albanians are seen to be the lapdogs of the Americans.”

Schwartz refers to a palpable, on-the-ground popularity of the US in Albania and Kosovo, almost entirely due to NATO’s involvement in the tail end of the Yugoslav Wars; specifically, the allied bombing of Belgrade, capital of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY), now the Republic of Serbia. NATO and FRY officials signed an agreement mandating full withdrawal of Serbian troops from Kosovo in late 1999, which paved the way toward an independent Republic of Kosovo, officially declared in Feb. 2008. Though there is measurable interaction and occasional cooperation between Kosovo and Serbia, the latter has yet to recognize Kosovar independence.

And this might partially explain why Kosovars lack the international support lent to other statehood efforts, like that of the Palestinians.

“The hypocrisy of refusing to recognize Kosovo is an unbelievable thing,” Schwartz says. “Certain Arab countries and members of the OIP won’t do it because Kosovar statehood was assisted by America. Kosovo was liberated by America.”

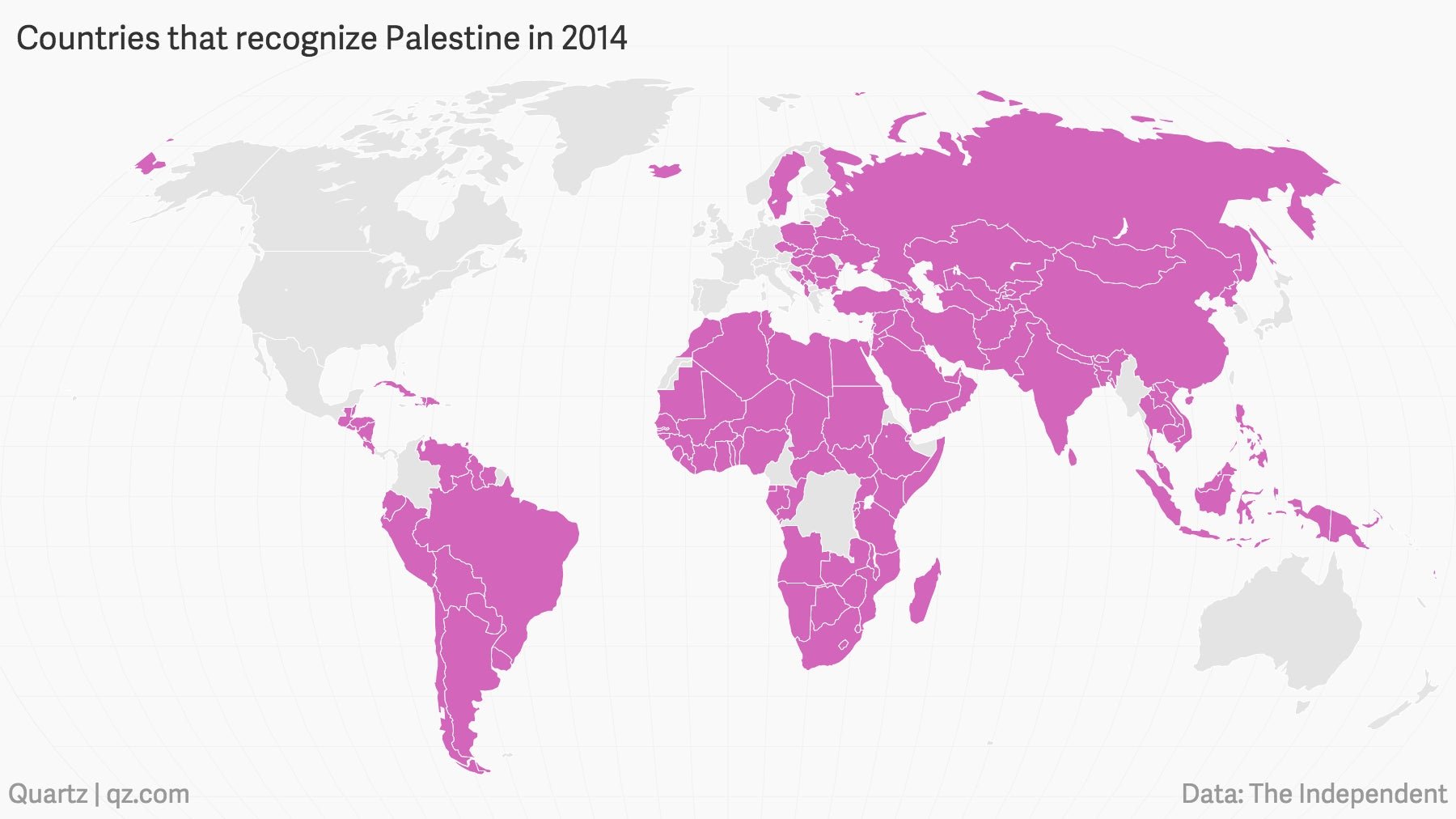

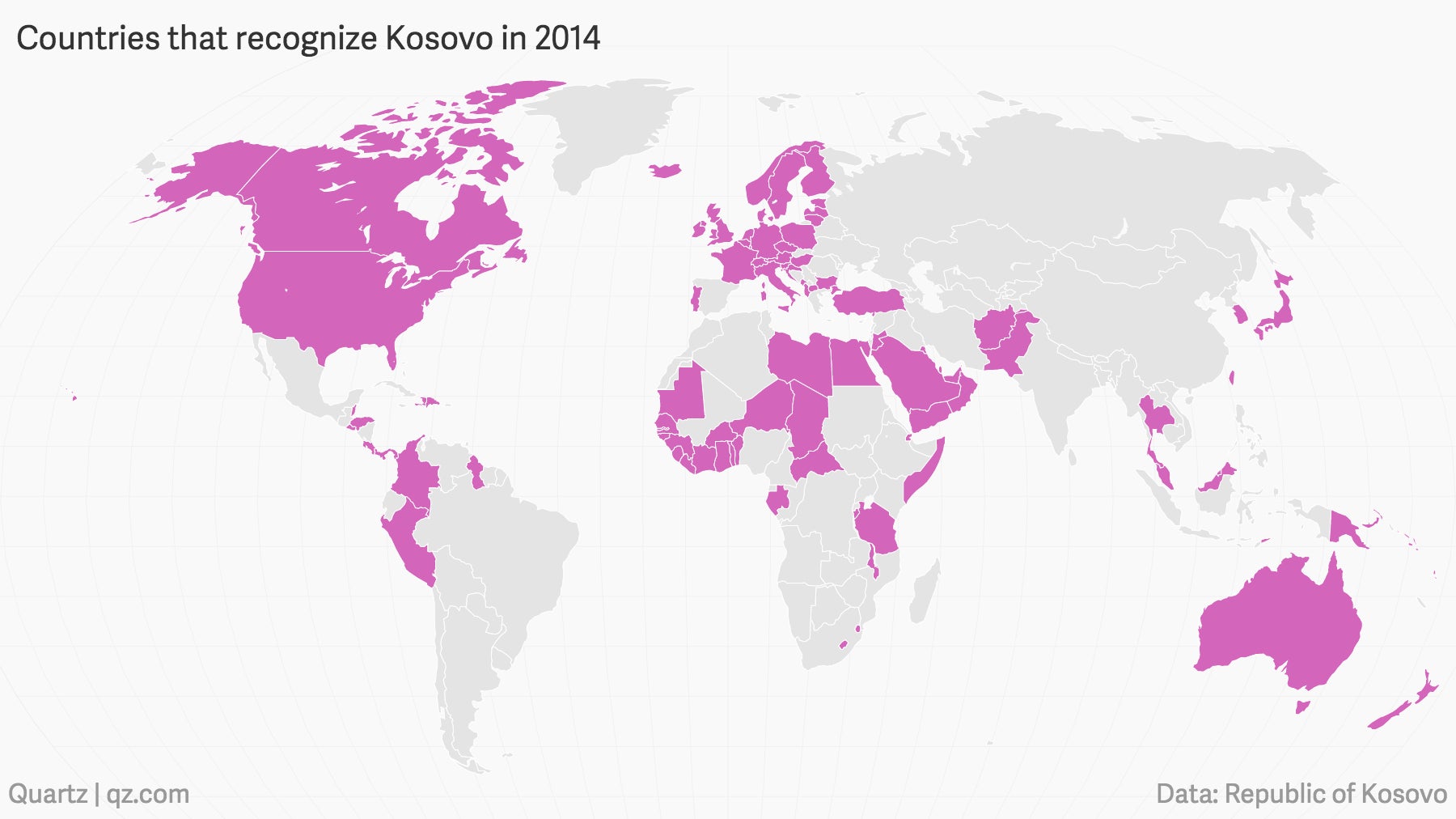

In fact, when looking at respective lists of countries that recognize Palestine and/or Kosovo, the divide runs rather cleanly along factional lines:

With some overlap in Latin America, the Middle East, Scandinavia, and Africa (the British parliament’s Oct. 2014 vote to recognize Palestinian statehood was non-binding), the allegiance to Kosovo or Palestine can be distilled to a given country’s attitude toward the US. With the exception of Libya, Egypt, and Pakistan, most Middle Eastern supporters of Kosovar statehood are also strategic US military allies: Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, and Jordan.

Predictably, Iran and North Korea recognize Palestine, but not Kosovo. Russia, a long-time ally of Serbia—which insists Kosovo to be part of the ancestral ethnic-Serb homeland (Raska)—recognizes Palestine, but not Kosovo. Members of the Moscow-led Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)—Belarus, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, etc.—follow suit.

The remaining BRICS (China, India, Brazil, South Africa) recognize Palestine, but not Kosovo; perhaps in some spirit of defiance against the “old guard” of geopolitical order—countries like Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and most of the EU, all of which recognize Kosovo, but reject Palestinian statehood.

The divide plays out even further along traditional international rivalries. Colombia recognizes Kosovo, not Palestine; Venezuela recognizes Palestine, not Kosovo. Pakistan recognizes Kosovo; India and Bangladesh do not. Azerbaijan recognizes Palestine; Armenia does not.

Though beyond the seemingly simple cartographic representations, the issue of limited recognition gets pretty complicated. There are some conspicuous ambivalences. Mexico recognizes neither Palestine nor Kosovo, perhaps in part to appease both the US and its Latin American (largely pro-Palestine) neighbors. Nor does Greece recognize either, perhaps because it has stood close to the flame of Balkan interethnic violence for centuries, and lies just a few hundred nautical miles the west of Israel.

Israel, interestingly enough, does not recognize Kosovar statehood—probably because the establishment of an ethnic-Albanian state on formerly Serbian soil would set a precedent for Arab-Palestinian secession. You’ll see similar mentalities at practice in Spain, which has historically struggled to keep hold of its Basque and Catalan regions; Morocco, which maintains a claim on the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (Western Sahara); China, for obvious reasons regarding Taiwan, Tibet, and the Uighur region; and the Russian Federation, which seems to make the bulk of its foreign-policy decisions based on whether a given move might inspire, or stoke extant secessionist sentiments in its outer republics.

This ultimately renders humanitarian appeals for recognition in Kosovo and Palestine (and Abkhazia, and eastern Ukraine, and Kurdistan) rather dishonest. The nations in question, the actual people vying for self-determination, are championed by their respective supporters as suffering nobly under the yoke of amoral oppressors. To the pro-Kosovo faction, big-bad Russia and little-bad Serbia impede international recognition for the sake of being bad. To the pro-Palestine crowd, big-bad America and little-bad Israel deny Palestinian sovereignty within the same, moralistic, black-and-white framework.

All parties seem to use righteous indignation to their political advantage; except, of course, the parties with the most tangible stakes: the Kosovars and Palestinians. They are minimized to little more than chess pieces—pawns, in fact, the most disposable of chess pieces—buffeted between elite players in the great game of 21st century realpolitik. A game that, for these would-be states, offers no discernible prize.