Nike is fighting three legal battles to protect the brand’s design soul

Nike is currently embroiled in three legal struggles, one over copyright and two over intellectual property, with massive implications for the brand’s reputation and bottom line.

Nike is currently embroiled in three legal struggles, one over copyright and two over intellectual property, with massive implications for the brand’s reputation and bottom line.

The sneaker behemoth’s deep pockets give it an advantage in court, but also mean it has a lot to lose. Perhaps more important for Nike, though, is what else is at stake in these lawsuits, which center on integral aspects of the brand’s design: its heritage, its reputation as a innovator, and its talent.

(Quartz has reached out to Nike for comment on each of the cases and will update with any response.)

Here are the legal battles underway:

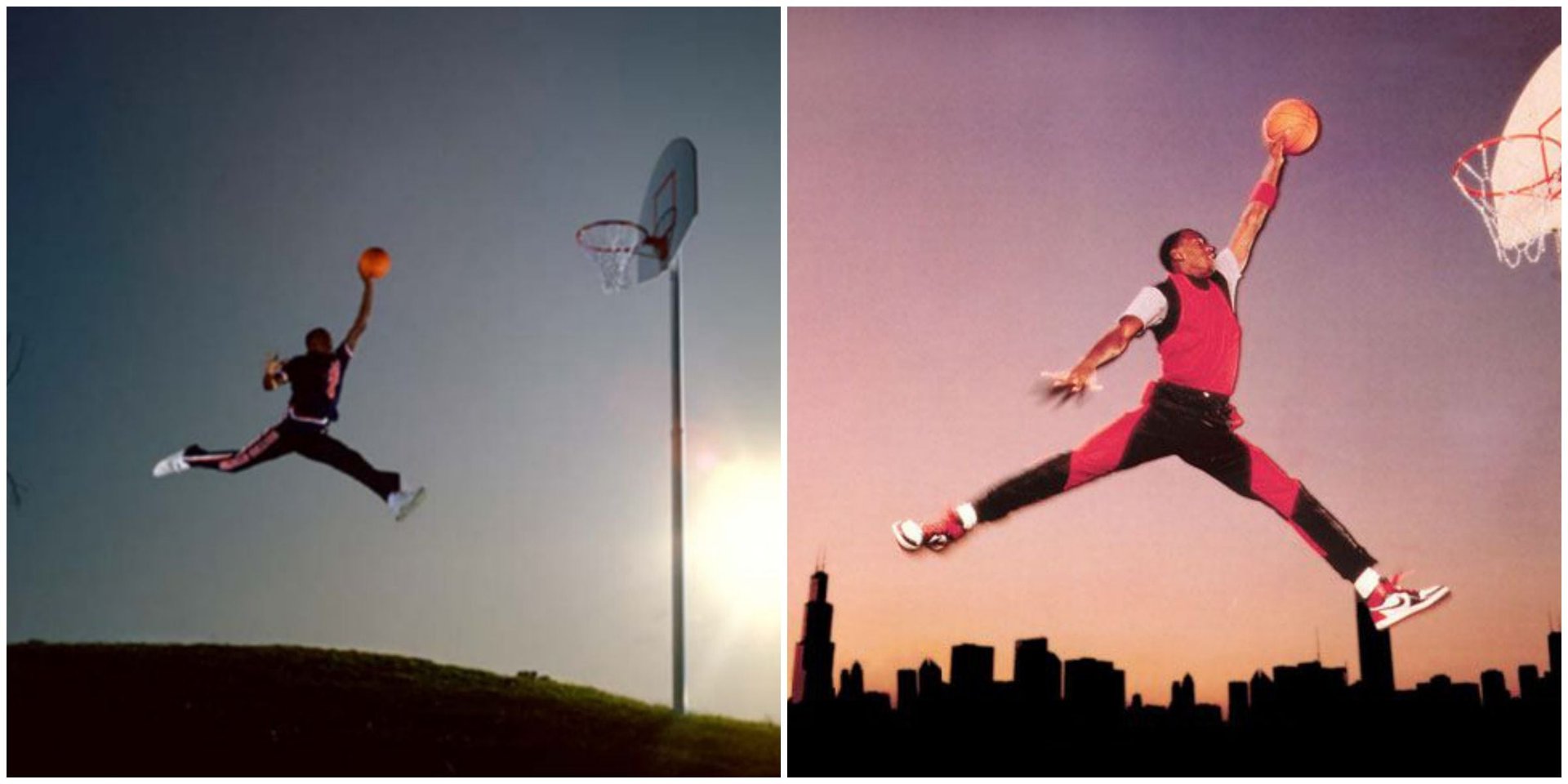

The “Jumpman” logo

Nike has been hit with a suit claiming that its iconic, ubiquitous “Jumpman” logo, the silhouetted image of the basketball superstar Michael Jordan with his legs spread and arm extended found on billions of dollars worth of Jordan brand sneakers and apparel, owes its existence to a photo taken for Life magazine, and violates the copyright of that image.

The story starts back in the summer of 1984, when a photographer named Jacobus Rentmeester took a picture for Life of a flying Michael Jordan in midair as he dunked a basketball. Rentmeester’s infringement suit, filed in a Portland, Oregon, district court in January, alleges that after the image ran in Life, Nike paid Rentmeester to temporarily use transparencies of his image “for slide presentation only, no layouts or any other duplication.”

Nike then created its own Jordan image, very similar to Rentmeester’s original, and started using it in ad campaigns.

Rentmeester complained to Nike that its image was essentially a duplicate of his, and in response, Nike paid him $15,000 to keep using the photo it created, he says. An invoice (not a contract) for the $15,000 submitted as part of the filing specifies that Nike’s photo was to be used “for North America only” for two years, with all other rights reserved by Rentmeester. In 1987, Nike unveiled its Jumpman logo, a silhouette of the image Nike created, which Rentmeester says copied his original.

Almost 30 years and billions in sales later, Nike is still using the Jumpman, and Rentmeester wants an unspecified share of the cash the company has made with it. But even a small part of the revenue made on products using the image would be significant. Jordan sneakers had estimated sales of more than $2.6 billion in the US in 2014 alone, according to SportsOneSource.

Michael Jordan and the sneakers bearing his name and image helped make Nike into the sportswear giant it is today. So even a temporary injunction to stop Nike from using the image would be a serious headache for the brand. And a Jordan product without the Jumpman logo is almost unimaginable.

Nike has already hit back. On March 16, it filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, saying Rentmeester’s complaint is “meritless” and fails to meet the standard for infringement. “Simply put, Rentmeester does not have a monopoly on Mr. Jordan, his appearance, his athletic prowess, or images of him dunking a basketball,” Nike testily added in its filing.

Sneakers with knit uppers

In 2012, both Nike and Adidas introduced their first knitted running shoes. Each had been developing its version for years, but Nike patented its technology and beat Adidas to market, putting out its Flyknit sneakers in February of that year. Adidas’s Primeknits followed in July.

It wasn’t long before Nike accused Adidas of infringing on the patent it held for its high-tech, woven, one-piece uppers, which it saw as a “game-changer” in the industry and a symbol of its innovation as a brand. (Quartz has reached out to Adidas for comment and will update with any response.)

After court battles in Germany, which Nike eventually lost, the case quickly moved over to the US. Adidas filed a petition in the US Patent and Trademark Office to invalidate Nike’s patent for “footwear having a textile upper.” It made the same argument that it had used in Europe: Nike was trying to patent technology that already existed and therefore could not be patented. The court ultimately sided with Adidas.

Nike hasn’t given up the fight, however, and in December filed an appeal claiming its patent is, in fact, valid. If Nike prevails, it would be a blow to Adidas, whose visibility in the US is already shrinking—it continues to lose market share, for instance, and won’t bid to renew its NBA sponsorship contract when that deal is up.

But the real victory for Nike would be to solidify its reputation as the top innovator in sneakers today. As far as sales go, Adidas’ Primeknits aren’t a big threat in the US. Last year, the most successful Nike Flyknit style, the Free 4.0+ Flyknit, was the 17th most popular running shoe for men, and the 20th most popular for women, according to data from SportsOneSource. They sold a combined $80 million. Adidas’ Primeknit didn’t even make the list of the top 250.

Trade secrets

The feud between Adidas and Nike got even uglier in September 2014 when Adidas announced that it had hired three senior designers—Marc Dolce, Mark Miner, and Denis Dekovic—away from its rival and was creating a new design office in Brooklyn, New York, for them.

It was about as personal a shot as Adidas could take at Nike, and has led to some very public airing of dirty laundry. The designers were among Nike’s top talent. Dekovic headed the company’s global soccer footwear program ahead of the World Cup and led the creation of the Flyknit Magista cleat. Dolce worked on signature sneakers for LeBron James, Kevin Durant, and Kobe Bryant. Miner developed new running and training products and was involved with staple lines such as the Nike Free, Air Max, and Zoom Air.

In December, Nike filed a $10 million lawsuit against the three accusing them of violating the non-compete agreements they had signed and taking proprietary secrets, such as unreleased product designs and marketing plans, to their new employer. The language made them sound like super villains:

“Nike’s Confidential Information [sic] remains in the clutches of individuals who induced Adidas to hire them by promising to deliver a ‘wealth’ of Nike’s information to ‘give Adi[das] the advantage,’ and who are certain to exploit the trade secret information,” Nike’s complaint said.

The filing said that the designers tried “to conceal their misdeeds” by wiping emails and data from their Nike-owned phones and computers, but Nike still came up with information to embarrass the designers and their new employer: Messages among them indicate that the designers didn’t really want to work at Adidas. They had hoped to create their own company, but lacked the money, so Adidas was the next best option.

The suit sought an injunction requiring that the designers turn over all confidential information, refrain from publicly associating with Adidas, and refrain from designing any footwear, whether for Adidas or independent projects. The day after Nike filed, it won a temporary restraining order against the designers.

Shots continue to be fired from both sides. Last week the designers filed a countersuit against Nike denying all allegations and accusing the company of breaching their privacy. Nike corporate culture, the filing said, was “stifling their creativity,” and they, “along with many of their design co-workers, were alarmed about the culture of distrust and intimidation” that exists between Nike executives and creatives.

Nike replied with a statement saying they stand by their claims.

It’s hard to see the designers’ move to Adidas doing Nike much harm in the US. The brand controls 45 percent of the market, compared to Adidas’ 5.6 percent, and Nike footwear sales in the US were $8.4 billion last year. Even if Adidas made up some ground, Nike’s dominance would not be challenged.

Still, Nike is now on the defensive on three fronts—and the ugly battle with Dekovic, Miner, and Dolce has shown some chinks in its armor. The threat isn’t so much to its present market share, but to the market share it wants to have years from now.