Happiness is a great metric for success, but how do we measure it in an unequal world?

Today, March 20, was dubbed International Happiness Day by the United Nations back in 2012. Designating a day for a state of mind was designed to recognize “the relevance of happiness and well-being as universal goals and aspirations in the lives of human beings around the world,” and the importance of making happiness a goal of public policy, the UN said.

Today, March 20, was dubbed International Happiness Day by the United Nations back in 2012. Designating a day for a state of mind was designed to recognize “the relevance of happiness and well-being as universal goals and aspirations in the lives of human beings around the world,” and the importance of making happiness a goal of public policy, the UN said.

The goal is laudable–and incredibly difficult. There are problems with measuring happiness in a world so fundamentally unequal. And while happiness is a feeling not hard to express (as the video below illustrates) it is very hard to quantify.

How are we doing?

The UN’s goal is to place happiness more centrally in our thinking about how well we are “succeeding” as a global community. Ban Ki Moon, the UN secretary general, noted in 2012 that for too long the world has used Gross National Product (GNP) to measure wellbeing—a practice that could be likened to asking someone for a bank statement before deciding whether to dance with them.

Created in 1937 as a reaction to the turmoil of the great depression, GNP is useful for some things, but hopelessly limited, Ban said. Another set of measures, the Human Development Index, launched 23 years ago, sought to redress the limitations of the single metric, which had even concerned Simon Kuznets, the originator of GNP.

Ban commended Bhutan, which since 1971 has eschwed GNP and instead measured Gross National Happiness. “Connecting the dots…between water, food and energy security, climate change, urbanization, poverty, inequality and the empowerment of the world’s women—lies at the heart of sustainable development,” he noted in a speech.

Ban’s list, rational though it is, points to a problem with measuring happiness: The world is so fundamentally unequal that happiness is far from a fixed target.

Most people in the developed world spend more time thinking about coffee than worrying about water, for example. Yet prosperity alone doesn’t automatically bring an absence of cares. Westerners laugh at themselves for experiencing “first-world problems” (“my latte wasn’t hot enough,” “choosing a neighborhood to live in is difficult”), but grief and hardship do not disappear because basic needs are met.

The empowerment of the world’s women, meanwhile, still means vastly different things in different places. In northern Europe, the conversation is about female talent being rewarded in the workplace, on an equal footing with men. In America, a major issue is still the right to abortion. In India, people are finally talking about rape.

Measuring happiness

“Happiness is an aspiration of every human being,” and can be a measure of social progress, said the authors of the 2013 World Happiness Report (pdf), one of the first of its kind. They noted that the key to measuring happiness is differentiating between happiness as emotion (“Are you feeling happy right now?”) and as an evaluation of human wellbeing (“Are you happy with your life as a whole?”). The next report is due out next month, on April 23.

Their research sought to focus on the latter. Some outcomes were unsurprising: Denmark led, and other Scandinavian countries were among the happiest places on earth. Togo, Benin, and several other sub-Saharan African countries where poverty is high were among the least happy.

But other results didn’t follow obvious economic lines. Costa Rica was the 12th-happiest country, far above Germany, in 26th place. Uzbekistan (60th) and Angola (61st) were both happier places than China (98th) or India (111th).

Overall, the researchers found that, in the five years prior to the report, the world had become a slightly happier and more generous place.

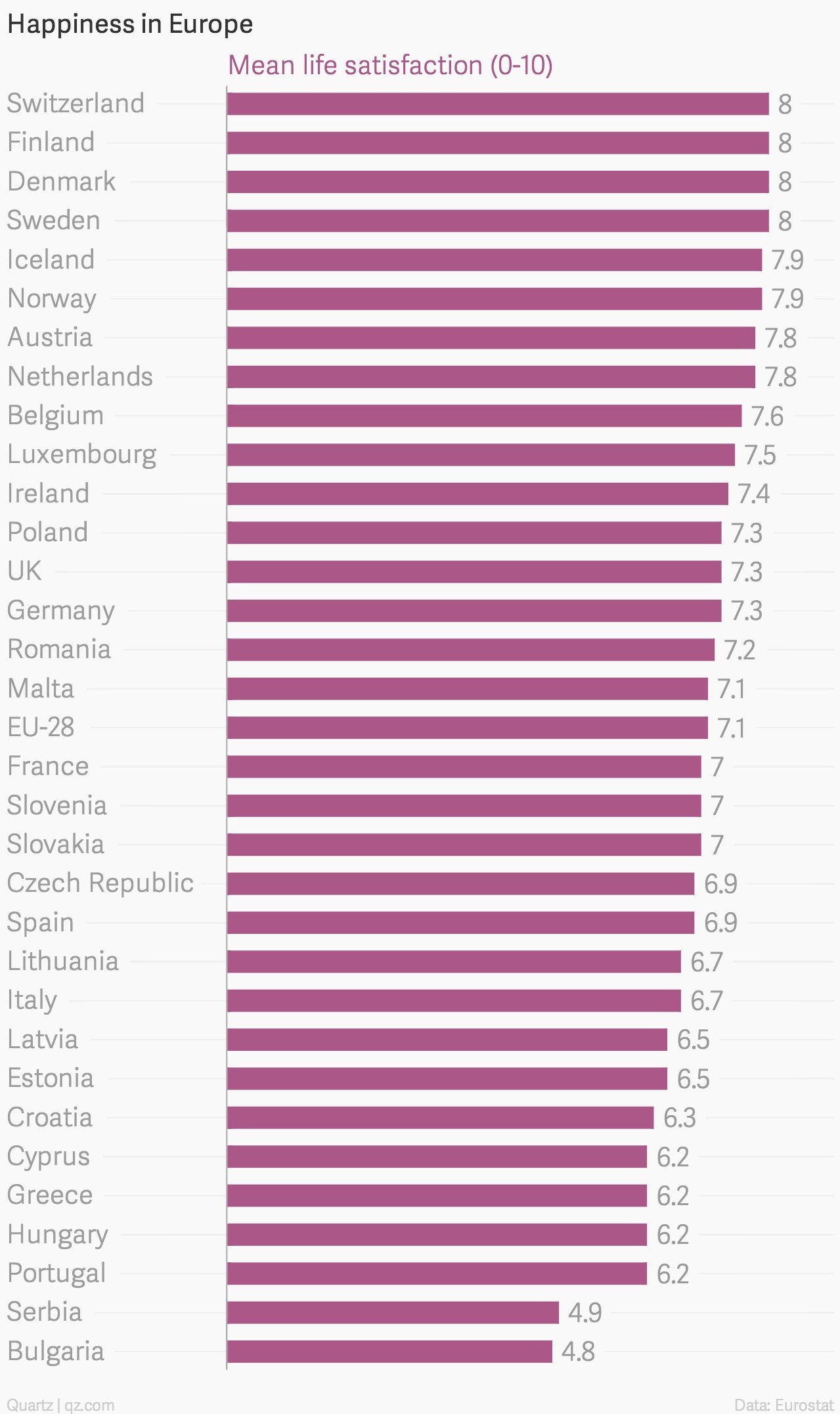

The findings are mirrored in another recent piece of research, by Eurostat, focusing on Europe. Far from getting less happy, the respondents’ lives were reportedly improving.

In the European study, wellbeing was seen to consist of three distinct elements: life satisfaction, the presence of positive feelings and absence of negative feelings, and eudaimonics–the sense that one’s life has a meaning.

A human right?

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, enshrined as “unalienable rights” in the American Declaration of Independence, are goals not yet possible for everyone to achieve—in that country or elsewhere.

In particular, societal violence and disruption, caused by internal conflict or external attacks, has a clear effect: The 2013 report found that people were becoming less happy in the Middle East, for example, where countries including Syria, Libya, Iraq, and Israel and the Palestinian territories have seen high levels of violence and displacement for several years.

But the same research also found that a major cause of unhappiness was something that could occur in any society: mental illness.

“Mental illness is one of the main causes of unhappiness,” they wrote. “This is not a tautology…[since] people can be unhappy for many reasons—from poverty to unemployment to family breakdown to physical illness. But in any particular society, chronic mental illness is a highly influential cause of misery.”

The term is broad. It could relate to work-related stress or the trauma that comes with being displaced. But the researchers called on policymakers to recognize the sphere of the mind alongside external and societal problems.

Happy in its many forms

Leo Tolstoy famously wrote that while every happy family is the same, every unhappy family is unhappy in it’s own way. The observation is brilliant, because it says something about state of mind (how the unhappy see the happy) as well as making a comment on society at large. But it may not be right.

Happiness comes in many different forms, for different reasons, in different places. And yet similar things—the loss of a home, the pain of losing a loved one, a lack of basic necessities—make people unhappy the world over.

In England, today’s International Happiness Day is also the first day of spring, bringing with it a swell of shared hope. Winter is a hard time in northern climates, and spring speaks of rejuvenation and lighter times to come.

Philip Larkin wrote about all three concepts—the changing season, happiness, and its hard-to-define nature—in his poem Coming, excerpted here:

It will be spring soon,It will be spring soon —

And I, whose childhood

Is a forgotten boredom,

Feel like a child

Who comes on a scene

Of adult reconciling,

And can understand nothing

But the unusual laughter,

And starts to be happy.