Could the Arctic be the next Crimea?

Tensions have increased a notch in the Arctic with the news that the Russians have started a major military exercise in the region. Nearly 40,000 servicemen, 41 warships and 15 submarines will be taking part in drills to make them combat-ready – a major show of strength in an area that has long been an area of strategic interest to Russia.

Tensions have increased a notch in the Arctic with the news that the Russians have started a major military exercise in the region. Nearly 40,000 servicemen, 41 warships and 15 submarines will be taking part in drills to make them combat-ready – a major show of strength in an area that has long been an area of strategic interest to Russia.

Russia might be reshaping national borders in Europe as it reasserts its geopolitical influence, but the equivalent borders in the Arctic have never been firmly established. Historically it has proven much harder for states to assert sovereignty over the ocean than over land, even in cases where waters are ice-covered for most of the year.

For centuries the extent to which a nation state could control its coastal areas was based on the so-called cannon-shot rule – a three-nautical-mile limit based on the range of a cannon fired from the land. But this changed after World War II, leading to the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS) in 1982.

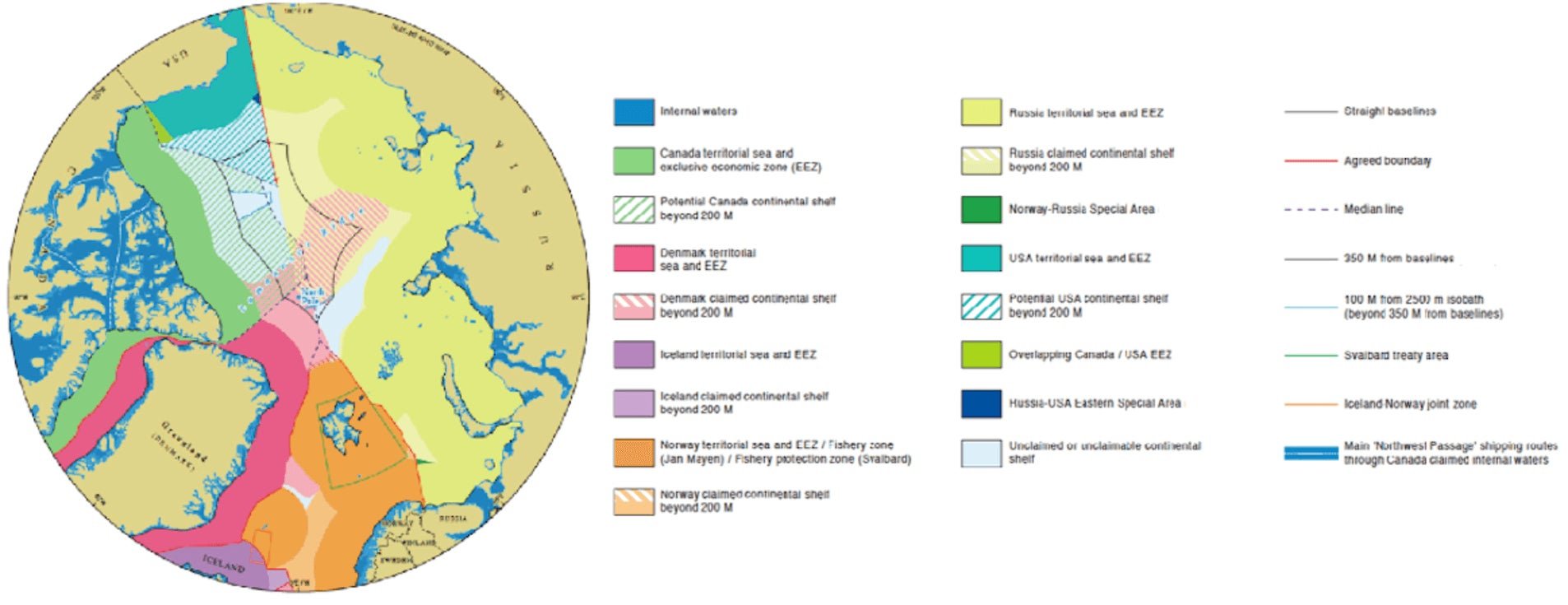

Under UNCLOS, every signatory was given the right to declare territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of up to 200 for commercial activities such as fishing and oil exploration. Signatories could also extend their sovereignty beyond the limits of this EEZ by up to an additional 150 nautical miles if they could prove that their continental shelves extended beyond 200 nautical miles from the shore.

Orderly settlement

It is quite common to read about a “scramble for the Arctic” in which the states concerned – Denmark, Norway, Canada, Russia and the US – race to carve up the region between themselves. In fact, this is not a very accurate description.

There are two dimensions to developments in the region – one legal and the other political. In legal terms, these five littoral states have sought to use UNCLOS to establish borders and assert their primacy over much of the Arctic Ocean and the seabed below (with the exception of the US, which is yet to ratify the convention).

Canada and Russia have also used the special provisions provided by Article 234 of UNCLOS – relating to the right to regulate over ice-covered waters – to strengthen their authority over emerging Arctic shipping routes (the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route).

In 2008 the five states issued the Ilulissat Declaration, committing to the “orderly settlement of any possible overlapping claims” using the legal framework provided by the law of the sea. This has been reflected in the continental-shelf claims they have submitted to the UN over the past 15 years: Russia (2001), Norway (2006), Canada (2013) and Denmark (2014).

These submissions are all claims for an extension of exclusive rights to continental shelves beyond 200 nautical miles from each land border. This leaves a small area in the central Arctic Ocean unclaimed but also raises issues about various territories where more than one state has posted a claim (see graphic below).

Among the claimants, Russia has been asked by the UN to submit further scientific evidence in support of its case. This has not yet happened to the other states, but since it will take time for their claims to be assessed, this may yet change. Until the US ratifies UNCLOS, it can’t submit a claim.

Insecure borders

Yet legal provisions only go so far. The question remains: what happens if the Arctic states become more assertive in the delimitation of their national borders?

Canada and Denmark have made significant commitments to backing up their claims, including developing new security strategies. In 2012 Denmark established a specialised military command to police its Arctic territories, for instance. But over the last decade, it is Russia that has advanced the most significant plans for building up its security forces in the region – even before its most recent exercises began.

In material terms, Russia currently has the most to gain from industrially developing its Arctic zone. The Russian Arctic contains significant reserves of hydrocarbons, diamonds, metals and other minerals with an estimated value of more than $22.4tn (£15.2tn). The area is already a major producer of rare and precious metals and important oil and gas fields.

This makes it easy to see why the Kremlin announced in 2008 that it will use the Arctic zone as a “strategic resource base” for the socio-economic development of Russia in the 21st century. In 2013 the Kremlin further observed that such development would be heavily dependent on foreign investment, technology and expertise.

Yet this apparent openness to international business interests has been accompanied by an intense sense of insecurity about Russia maintaining influence and authority in the region. It is wary of a Western bloc forming within the Arctic Council (the five littoral states plus Finland, Iceland and Sweden) and has preferred to engage the other Arctic states on a bilateral or regional basis. Russia is particularly concerned about the potential for the EU and NATO to become more active in Arctic affairs, given that all of the other Arctic states are members of one or both of these organisations.

Vladimir Putin has spoken publicly about the need to keep tensions to a minimum in the Arctic, while embarking on its extensive military and security programme in the region at the same time – not least establishing a new Arctic strategic command last December.

The Kremlin showed in its response to the “Greenpeace 30”, who tried to seize a Russian oil platform in 2013, that it will not tolerate any threat to its economic activities in the Arctic, nor allow any precedent that might undermine its authority over what it essentially regards as its territorial waters.

Future uncertainties

Russia will submit a new claim for the extension of its outer continental shelf to the UN in 2015 (encompassing an area of roughly 1.2m sqkm). Already state officials in Russia are positioning the situation as a test of whether the international scientific community will accept Russian science.

A second rejection of Russian claims in the Arctic might further feed Russian concerns about being kept down and encircled by Western rivals. On the other hand, if Russia’s claim is accepted, the rest of the international community might quite rightly become concerned about how the Kremlin will exert its authority within such significantly expanded borders in the Arctic.

The deterioration in Russia’s relations with the West is only likely to up the stakes for the Kremlin when it comes to settling its maritime borders in the Arctic. Russia has remained engaged in the Arctic Council and has repeatedly called for the Arctic to remain insulated from the fallout from Ukraine. Yet in the coming years, Russia’s neighbours are likely to remain wary about how exactly the Kremlin plans to negotiate and secure its borders along its Arctic frontier.