China’s heating up twice as fast as the rest of the world

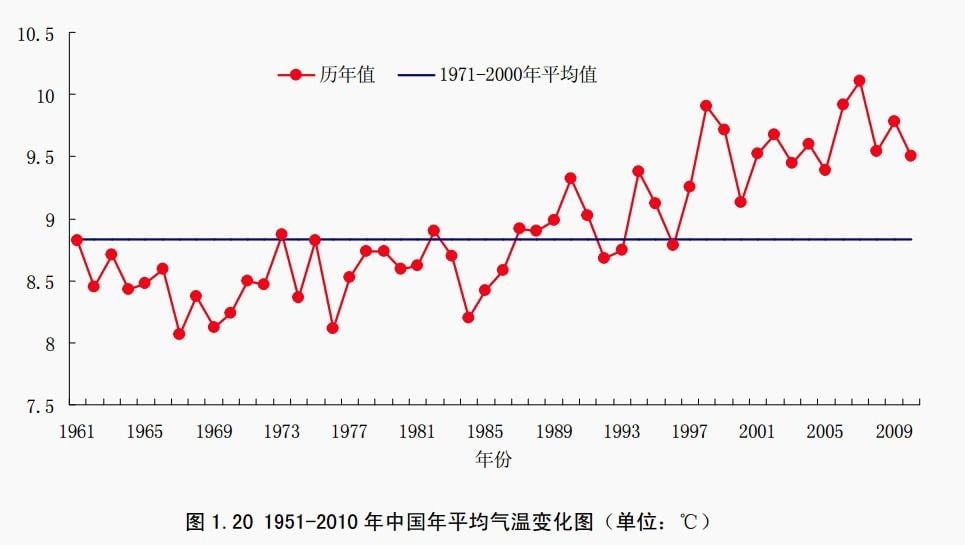

The average surface temperature in China has increased by 0.23°C (0.4°F) each decade of the last 65 years, said a Chinese government official—twice the average pace of warming everywhere else on the planet.

The average surface temperature in China has increased by 0.23°C (0.4°F) each decade of the last 65 years, said a Chinese government official—twice the average pace of warming everywhere else on the planet.

This isn’t the first time the Chinese government has quantified the effects of global warming on its environment. However, today’s remarks are a break with previous statements that China “has basically kept pace” with the warming experienced by the rest of the world.

The remarks were also unusually grave. Since 2000, weather-related disasters have cost China 1% of its GDP, eight times more than the global average, said Zheng Guoguang, head of China’s meteorological administration, in a speech earlier today (link in Chinese).

The future Zheng outlined is even bleaker. As greenhouse gas emissions accelerate global warming, the destruction China faces as a result of climate-related disasters will intensify, he said. These risks could have a dire impact on food production, water supply imbalances, and on major strategic infrastructure projects like the Three Gorges Dam and the South-North Water Diversion.

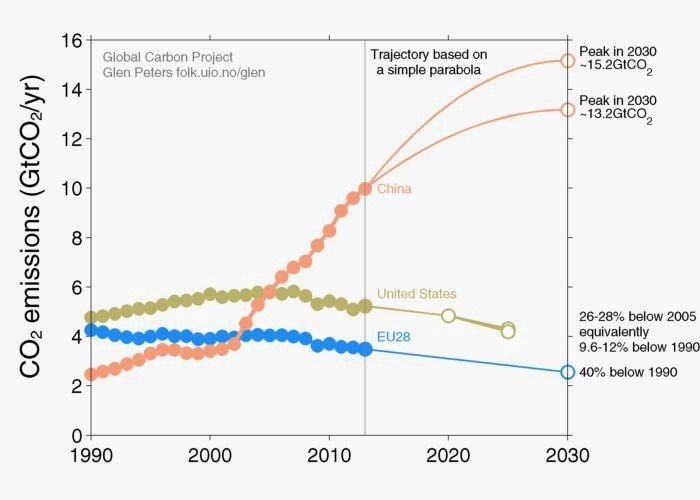

China produces more of those greenhouse gases than any other country—more than the US and EU combined—even though on a per-capita basis, its emissions are much lower than the US’s and other developed countries.

That’s in large part related to China’s heavy reliance on coal, a cheap and plentiful source that’s long fueled the country’s capital-intensive growth model. China accounts for half of global coal consumption.

That nasty coal habit is partially responsible for the noxious smog that blankets many parts of China, which sends an estimated 670,000 Chinese people (paywall) to an early grave each year. In response to growing outrage about air quality—most recently captured in the smog documentary ”Under the Dome,” which went viral in China before the authorities censored it—the government has been stepping up environmental rules and instituting ambitious plans to cut coal use, including capping coal consumption by 2020.

While many have hailed China’s Nov. 2014 pact with the US as a sign of its commitment to cut greenhouse gas emissions, some researchers have noted that its commitments are too vague to be meaningful. Still others fear that the government’s frenzy to cut coal consumption—the easiest way to reduce air pollution in its biggest cities—could lead to more reliance other carbon-intensive energy sources, which might only increase greenhouse gas emissions. At least Zheng’s dire prognosis shows that some of China’s leaders know cutting emissions should also be an urgent priority.