The latest challenge in design? Create a better way to die

It’s fair to say most of us don’t have a very good relationship with death.

It’s fair to say most of us don’t have a very good relationship with death.

At least not in the West, where one in three Americans say they would ask doctors to do anything possible to keep them alive, according to a Nov. 2013 Pew poll, and only one in three UK adults have prepared a will.

To fight off death, we’ve founded research groups like Google-backed biotech company Calico, whose mission is to halt the aging process, and the $1 million Palo Alto Longevity Prize, dedicated to finding scientific cures for old age. All are signs of what US anthropologist Ernest Becker identified in 1973 as a civilization-wide “denial of death,” in which the sum of human activity is simply an expression of our inability to accept the inevitable.

But we have to get over it. Humans should apply their creativity and innovative power to redesigning the inevitable, not futilely inching away from it. Quantified Self products like the new heart sensor-equipped Apple Watch are designed to help you hack your own body into a more efficient, longer-lasting, biological machine, but a world of widespread longevity would be a mess.

Current human society is designed around a 100-year-or-less lifespan. Saving enough money to sustain just a few decades of old age is already hard. Who has the savings to retire forever?

The more useful and meaningful innovation would be not how to live longer, but how to die better.

How we think about death

We struggle to plan for death because the assumptions we hold about dying are formed by what we see around us. It should be telling that the death scene voted “most iconic” in a March 2015 poll of UK movie audiences is neither real, nor human: it’s the death of Mustafa in Disney’s The Lion King.

Pop culture has left us deeply misinformed. Popular television shows like US hospital drama ER have been found to portray a grossly unrealistic CPR resuscitation success rate of 75%, while in real emergency rooms, the survival rate is less than 10%. And even if, once in a while, we may tear up over a hero or heroine’s onscreen death, the cameras always pass quickly on to the next scene—characters die, but the story always continues.

Now, not only do we want to live forever, we suspect it’s possible. And the few deaths that we see are romantically misconstrued as noble, painless, fleeting, until we come to our own and realize—too late—that dying is not that simple.

We could be dying better

The most common way to die is the hospitalized death by natural causes, an involuntary, drug-smoothed transition usually overseen by health professionals who have lost the long struggle for the patient’s life. About 50% of people in the UK (and two-thirds of the elderly) die in hospitals, even though, according to the BBC, only 7% of British people say they want to die there. Most would rather die at home.

In the Medieval tradition, “how to die well” was first prescribed by the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying): an illustrated guide to preparing the mind, body and soul for death (and the first book to be printed on moveable type, after the Bible). Then, as now, planning a good death meant caring for the whole needs of the terminally ill person: not just medical, but social, psychological, emotional, religious and spiritual.

People who die a good death often do so because they are ready to die: if still mentally alert and lucid, they can prepare by resolving lingering conflicts, seeking counsel and eventually coming to terms with fate. Importantly, those who are prepared to die are often surrounded by loved ones, and arrange to receive care that maintains their self-respect.

To die with dignity, some choose to go before they lose control of their bodies or minds. Right-to-die supporters have already succeeded in legalizing voluntary euthanasia in places like Oregon in the United States, the Netherlands and Belgium. And popular support for death by choice is spreading; seven out of 10 Americans surveyed in a June 2014 Gallup poll think that physician-assisted euthanasia should be available for terminally ill people. In the UK, assisted dying is expected to be legal within two years.

The way we die is going to change

This is the beginning of a cultural shift toward death, a grassroots movement to fill in the gap between traditional, spiritual care and institutional, medical treatment, by creating new ways to die well.

Death doulas or death midwives, scattered through cities across the United States and Europe, have started offering practical and emotional support services around dying, often to perfectly healthy people. Alongside them is a growing network of Death Cafés around the world: groups of people who meet online and then gather in person to discuss dying over chocolate cake and cappuccino.

Breaking the stigma on public expressions of mourning and loss, in July 2013, National Public Radio journalist Scott Simon live-tweeted his own mother’s death. Outside of traditional institutions, many people are talking, connecting and passing on wisdom about how to approach our demise. These initiatives represent the DIY side of redesigning death.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, driven by advances in computing, US tech company eterni.me claims it will soon offer algorithmic facsimiles of deceased loved ones, which live on in cloud servers. Google’s Inactive Account Manager, deletes or shares deceased users’ data according to instructions left behind, while Facebook app My Memorials creates digital obituaries, guest books, and photo albums. All fall into a range of digital death services now emerging in the field of thanatosensitive design, from Thanatos, the Greek god for death.

My own design research studio Being and Dying builds products and experiences that re-integrate death into life. One project we are working on, codenamed Flutter, was designed to help adolescents grieve the loss of a loved one by expressing themselves with sound, instead of words, after our research showed that adolescents— though highly connected through their devices—tend to self-isolate during difficult periods of loss.

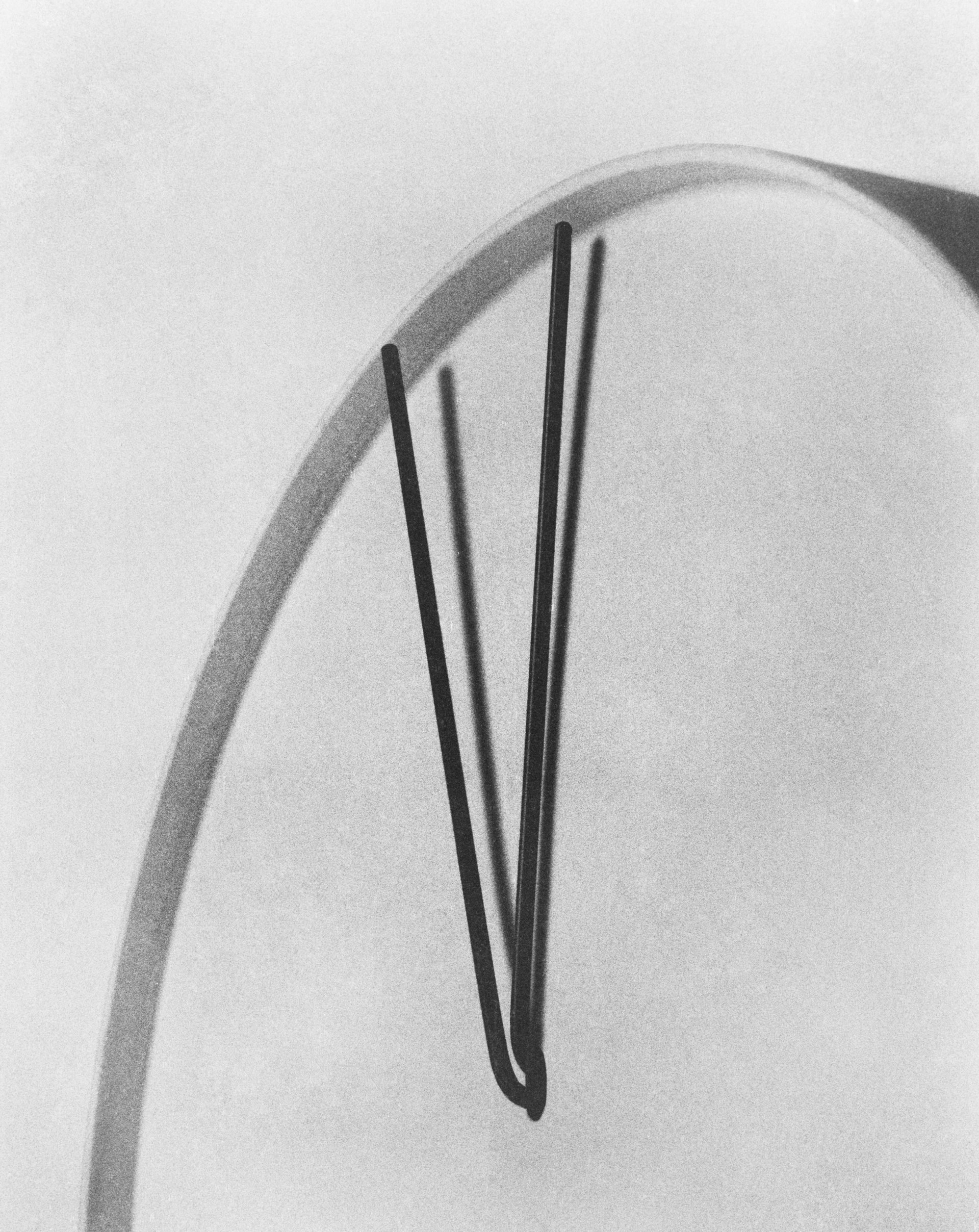

We’ve also built a wall clock to remind owners of the simple fact of being alive, right now. The arms of the clock gently move with your heartbeat, using heart rate sensors similar to those found in the Apple Watch. It only stops when your heart does. The clock, called Uji, embodies a Zen philosophy of time: that we should understand that we are always in time, not before or after it.

Nothing can save us. But with design we can help bring death into the everyday, and help people think more about how they want to conclude their lives. By taking careful stock of changing Western attitudes toward death, and by relinquishing the taboos on discussing death, creators of emergent products and services are helping us accept our own mortality. What we need is a new art of dying.