The truth about breakfast: you don’t need it

Much has been made about the importance of a good breakfast to a healthy lifestyle. It gives you energy to start your day, according to conventional wisdom, and scientific studies conducted a decade ago had proclaimed that eating breakfast was the key to maintaining a healthy weight.

Much has been made about the importance of a good breakfast to a healthy lifestyle. It gives you energy to start your day, according to conventional wisdom, and scientific studies conducted a decade ago had proclaimed that eating breakfast was the key to maintaining a healthy weight.

Breakfast skippers are plagued with well-meaning spouses, partners, family members, and friends, all insisting that they should eat something in the morning. But, according to nutrition scientist P. K. Newby, that advice was based on what’s known as observational studies, in which scientists follow groups of people and observe the outcomes. The result had seemed to indicate that people who lost weight or maintained a healthy weight ate breakfast. The problem, Newby told us, is that those studies didn’t isolate breakfast as the important factor. It could be, she says, that those who lost weight also exercised more, or one of dozens of other variables.

Then, in 2014, a group of researchers at the University of Alabama published a study that took a more rigorous look at this question. They enlisted 300 participants and randomly assigned them to eat breakfast, to skip breakfast, or to simply go about their normal routine. After 16 weeks, they found no difference in weight loss among the three groups.

Meanwhile, in a similarly controlled Cornell University study, people who skipped breakfast consumed fewer calories by the end of the day. And, in a smaller study at the University of Bath, people who skipped breakfast also seem to have consumed slightly fewer calories during the day, though they then expended slightly less energy.

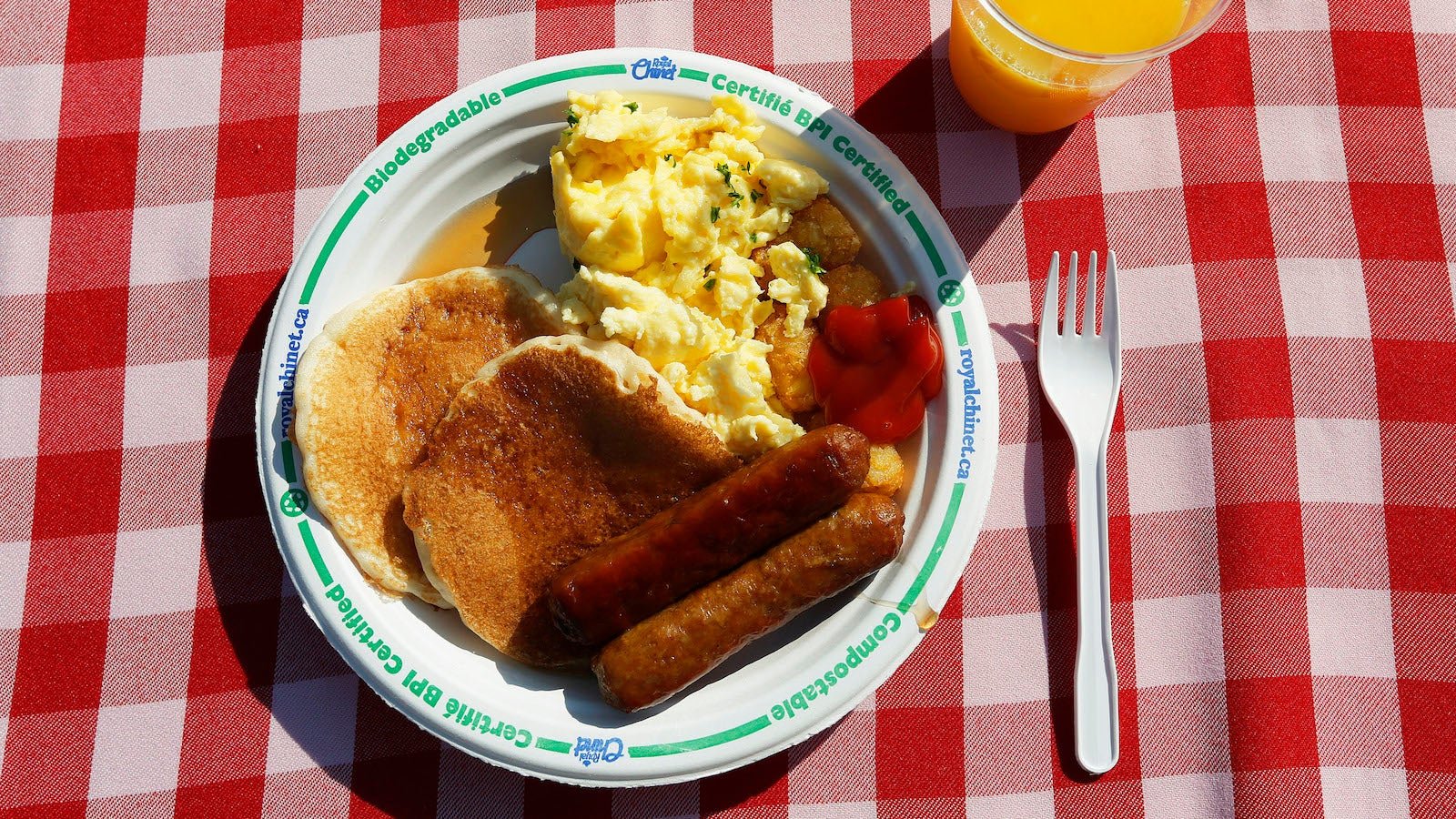

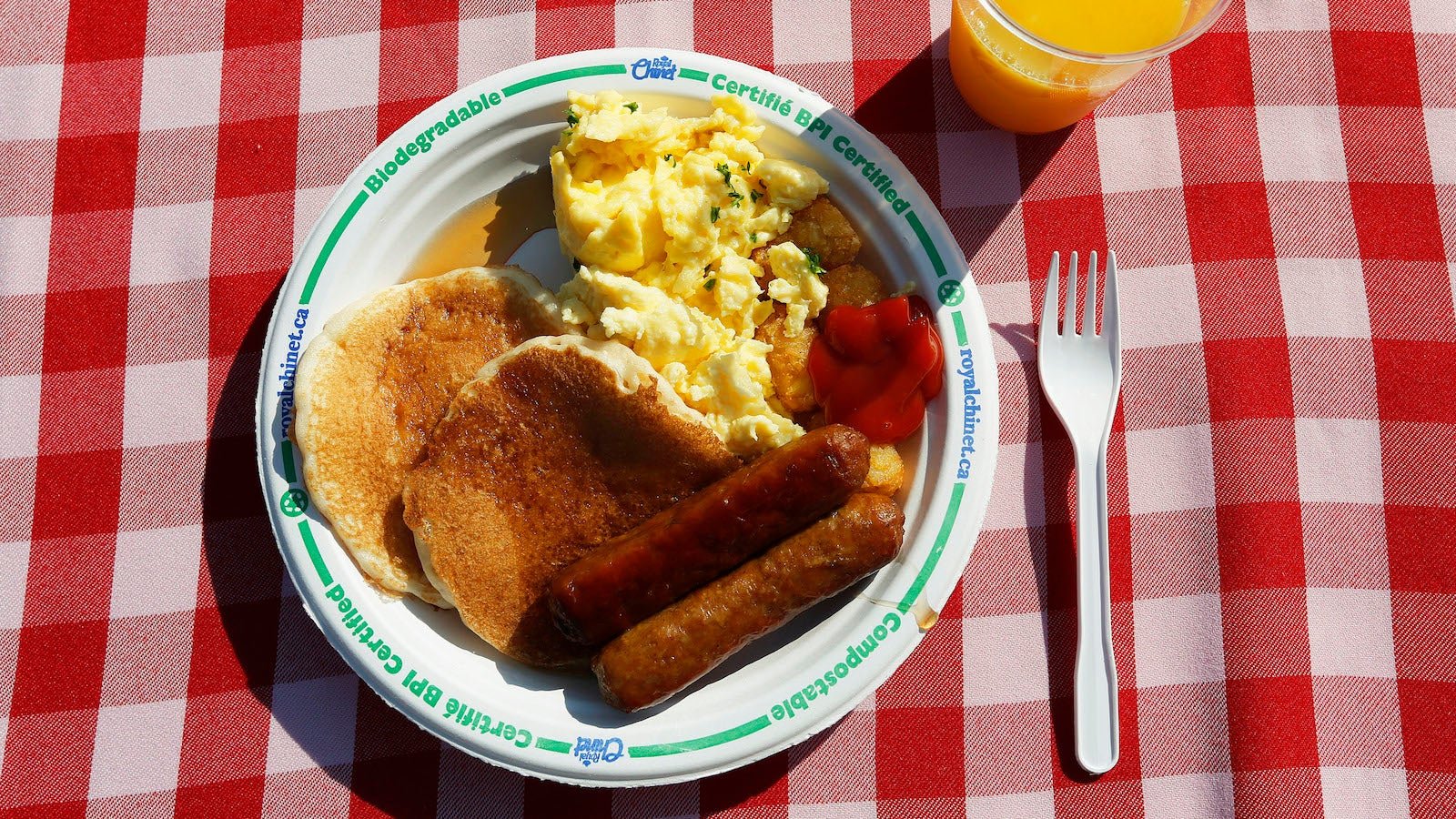

Based on this new research, the bottom line, Newby says, is this: if you’re not hungry in the morning, there’s no harm in skipping breakfast when it comes to weight management. “It’s the what that is more important than the when, when it comes to breakfast,” she says, which also means that grabbing a sugary muffin, doughnut, or other pastry, just to eat something in the morning, is a worse idea than eating nothing at all.

Reject the cult of juice

Everybody on the Internet has embarked on a juice cleanse. But you don’t have to feel guilty for sticking to solids: without the accompanying fiber in fruit, juice delivers a straight shot of sugar.

Juice, like sugary cereals, muffins, and white bread, is “quickly metabolized,” said Newby. “These foods lead to a spike in sugar and insulin, and then it dissipates. And so then, in a short period of time, you feel hungry again.” That, she continues, can lead to overeating and weight gain. And there are long-term health consequences as well: she says diets high in refined carbohydrates are a risk factor for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Newby says that the most important thing to understand about breakfast is that it’s simply another meal. It may seem as though we should eat only breakfast foods—cereal, juice, bagels—at breakfast time, but, as historian Abigail Carroll explains during this episode of Gastropod, that’s just a historical hangover from nineteenth-century American health reformers. And, as Newby points out, we already know what makes a healthy meal at any time of day: put vegetables at the center of the plate, accompanied by whole grains, beans, nuts, and healthy fats.

The first cup of coffee

Though Newby says that it’s what you eat that matters, not when, that may not be the case when it comes to coffee. We spoke to neuroscience PhD candidate Steven Miller, studying at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, about chronopharmacology, or the science of how brain chemistry interacts with drugs, in order to learn how timing affects the most popular stimulant in the world: caffeine.

Cortisol, the stress hormone that helps us feel alert and energized, peaks at about 8 or 9am, at least for people who work a typical 9-to-5 job and sleep during the same hours each night. Most people, says Miller, don’t need caffeine to give them a boost at a time they’re already naturally alert. In addition, drinking a caffeinated beverage at a time when you’re already sharp could lead to desensitization, which, Miller explains, means that you’ll need an increasing amount of the drug—in this case caffeine—to get the same effect.

For the best morning buzz based on brain biology, Miller recommends saving your coffee fix until 9:30am, when cortisol levels are starting to drop off.

He admits, though, that his recommendation doesn’t hold true for everyone: anyone whose sleep schedule is not regular or who works evening or night shifts will have a different cortisol production rhythm. In fact, he actually doesn’t follow his own chronopharmacological advice. Miller told Gastropod that, as a neuroscience PhD student, he works long, irregular hours and gets little sleep, and he always starts off his day, at any hour, with an extra strong caffeinated beverage.

The most capitalist meal of all

Miller’s decision to design his coffee routine around his work schedule, rather than biology, isn’t surprising given the history of breakfast. As we learn from journalist Malia Wollan, while breakfast foods may be different all around the world, it’s the first meal to change in immigrant households.

And, as Three Squares author Abigail Carroll explains, those classic American breakfast foods can be traced directly back to the Industrial Revolution and its transformation of labor—combined with some entrepreneurial innovations in processing, packaging, and marketing that were first pioneered in breakfast cereal but went on to transform the American diet. To learn more about the revolutionary history, global peculiarities, and surprising science of breakfast, listen to our latest episode!