Latin America’s middle-income trap

In 2014, GDP growth in Latin America slowed to less than 1%. Expectations for 2015 are just slightly better, with forecasters predicting growth of nearer to 2%. The downturn reflects external factors, including the European Union’s continuing problems, a slower China, and falling commodity prices. But it also results from domestic barriers that hold these nations back.

In 2014, GDP growth in Latin America slowed to less than 1%. Expectations for 2015 are just slightly better, with forecasters predicting growth of nearer to 2%. The downturn reflects external factors, including the European Union’s continuing problems, a slower China, and falling commodity prices. But it also results from domestic barriers that hold these nations back.

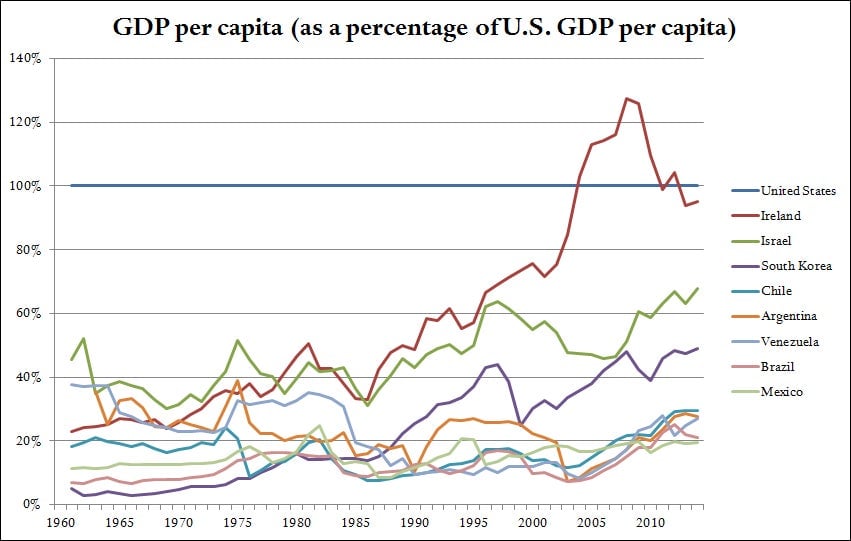

The vast majority of Latin American countries have transitioned from low- to middle-income countries, according to the World Bank. But most now remain mired in what economists call the “middle-income trap.” Only Chile, Uruguay, and a few Caribbean countries have joined the ranks of the world’s high-income countries. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) recent 2015 report, Latin American Economic Outlook, makes the case that the main barriers to climbing the economic ladder in Latin America are education, skills, and innovation.

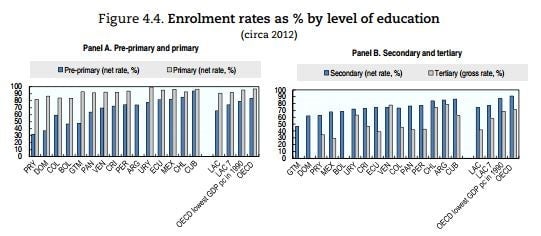

On the plus side, education spending has increased throughout the region. And so too has enrollment. Eighty-four percent of children now complete the primary grades. Still, schools underserve the crucial early years, as well as advanced study—pre-kindergarten and university enrollment are low relative to other OECD countries. What students get for their extra time in the classroom is also questionable—Latin American students score far behind their OECD peers on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) test. The test also reveals a strong socio-economic tilt—the wealthier the student, the better the score.

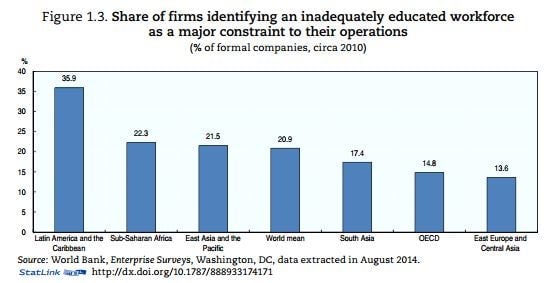

Coupled with weak educational systems is a skills mismatch. More than in other emerging economies, employers can’t find workers with the necessary abilities, particularly for more productive knowledge- and technology-intensive economic sectors. Instead employers face an unskilled labor surplus, many of which flood into the informal economy.

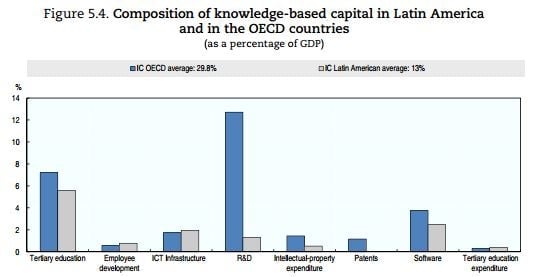

Finally, the report highlights the limited expenditure on “knowledge capital,” defined as a country’s capacity to both innovate and then disseminate those advances. Latin America spends on average 13 percent of GDP, less than half OECD rates. The region falls particularly behind in R&D expenditure (as opposed to tertiary education or information and communications technology infrastructure), a recognized driver of innovation.

So what can Latin American nations do? Education reform matters—revamping curriculum, improving teaching, and creating opportunities especially for those not in the upper echelons of society. Expanding technical and vocational training can also help develop the skills needed for new industries. And greater innovation—building up “knowledge capital”—will come from not just from more foreign direct investment in R&D-intensive sectors, but also by forging links between these multinationals and the rest of the domestic economy.

The path out of the middle-income trap is fraught—only a dozen or so newly emerging countries can boast GDP per capita rates comparable to those of developed economies today. But only with better policies can more Latin American countries aspire to join them.