Why the spending cuts in the fiscal cliff won’t solve America’s fiscal problems

The path to the US fiscal cliff has been a long one, and most of the coverage of it has been about raising taxes. While that’s largely because taxes are such a political sticking point, it’s also because the magnitude of tax increases scheduled for 2013 if America goes over the cliff—more than $500 billion, depending on how you slice it—far outstrips the $110 billion in scheduled spending cuts.

The path to the US fiscal cliff has been a long one, and most of the coverage of it has been about raising taxes. While that’s largely because taxes are such a political sticking point, it’s also because the magnitude of tax increases scheduled for 2013 if America goes over the cliff—more than $500 billion, depending on how you slice it—far outstrips the $110 billion in scheduled spending cuts.

Lawmakers are hoping to defer these cuts until they can come up with better-designed ones. Doing so would increase borrowing—which is, after all, the point of the talks—but it wouldn’t unduly exacerbate American profligacy, since the cliff cuts won’t solve the long-term problems in the health-care and defense spending. So while we wait to see if Republicans will allow a last minute deal to prevent cliff-diving (Congressional sources tell Quartz a deal reached by this Saturday, Dec. 29, could beat the clock) it’s worth looking at these two areas of spending.

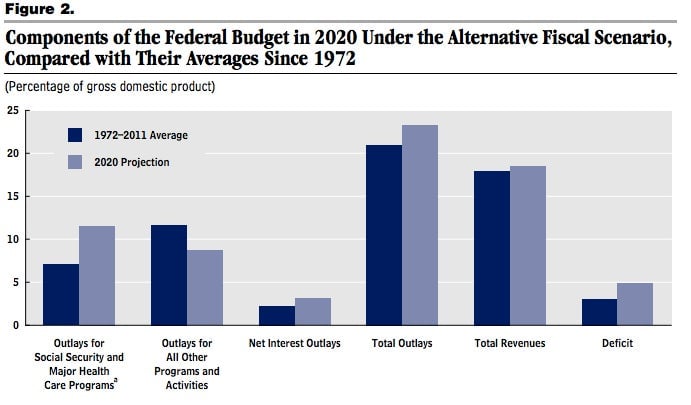

As always, we turn to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which compiles the data we need. Here’s a picture of the different components of the budget in 2020 under the “Alternative Fiscal Scenario,” which is CBO code for “current policy,” compared to their average over the last thirty years:

This chart basically says three things. First, spending is going up faster than revenues. Second, the reason that’s happening is that social insurance spending is increasing, thanks to the retirement of America’s post-World War II “baby boom” generation and the country’s incredibly high health care costs. And third, spending on everything else—defense, research, transportation, education, you name it—is lower than it would have been over the last thirty years. Indeed, it’s at its lowest levels since the Eisenhower administration in the 1950s. That’s a problem economically, because the kinds of investments that will help the economy grow tend to be in that now-shrinking category. In blunt terms, the government is spending less and less on preparing for the opportunities of the future, and more and more on looking after the elderly and poor today.

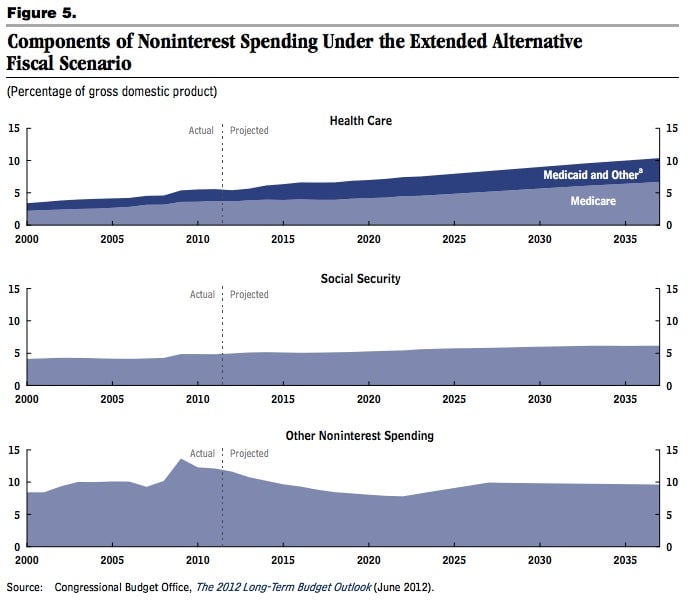

Let’s drill down into social insurance spending a little further:

The message here is a little clearer, and one that is a truism among budget wonks in Washington: While Social Security (pensions and disability benefits) costs will rise, they’re not the problem. The problem is spending on Medicare and Medicaid, the programs that cover the health costs of America’s seniors and poor. The US already spends nearly twice the average of other developed economies, as a share of GDP, on medical costs, without better results. (Also, ironically for a country that generally perceives socialized medicine as only slightly less evil than crack cocaine, America spends a bigger share of GDP on it than most.)

The problem with the fiscal cliff is that it cuts medical reimbursements, to the tune of $55 billion next year, without figuring out how to lower costs. When seniors freak out about that, as they have many times in the past, the political repercussions will probably mean reverting to higher spending.

The good news is that there is still time to “bend the cost curve” down on that explosion in spending. The bad news is that it isn’t easy to do and politicians don’t really agree on how. But many health-care economists are bullish that the 2010 health care overhaul provides at least the framework, by building more competition into the system, cutting payments to physicians and drug firms, and finding ways to make the system more efficient. Here’s some detail on how Obama would rather carve that spending back as part of a fiscal bargain.

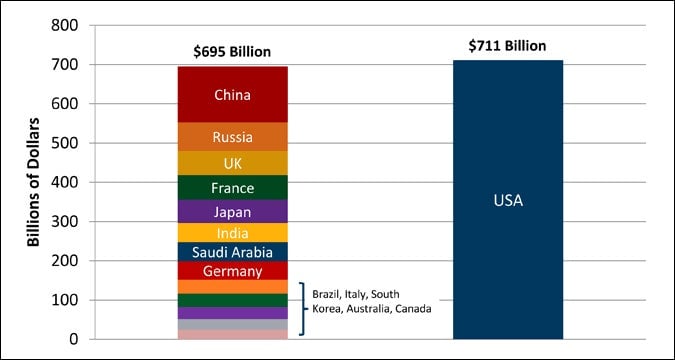

The other area where the US spends far more than other countries is the military:

The US actually spent $146 billion more on defense than it did on all of its non-social insurance spending in 2011—infrastructure investment, education, regulating banks, the whole nine yards. The fiscal cliff would take $55 billion out of next year’s defense budget, which has the Department of Defense complaining, since there’s still a war going on in Afghanistan.

But unlike in health-care spending, where both parties agree that reduction is necessary, reducing military spending remains a touchy subject. It’s bound to come up during confirmation hearings for President Obama’s new defense secretary in 2013. However, as with health care, the $55 billion of military spending cuts aren’t accompanied by an overall strategy for making national security cost less. Which means that, soon enough, Congress would find a way to kick in more money.

And when you add in the realization that cuts in yearly spending are being implemented at the fastest rate since World War II, the idea of adopting sloppy spending cuts, only to backpedal them later, now seems even stranger.