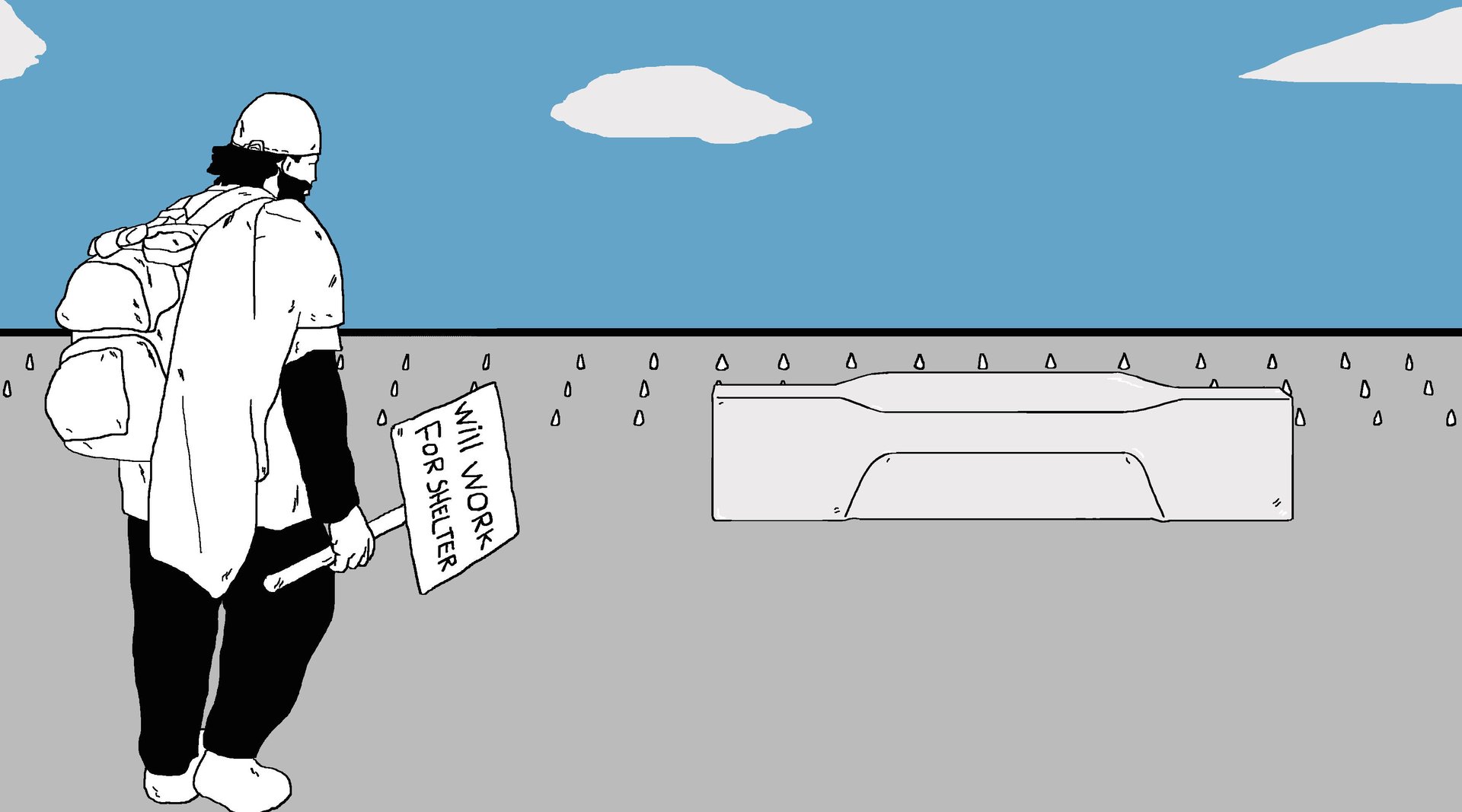

Architects are purposely designing uncomfortable park benches

Much of the contemporary discourse on urban design is rooted in acclaimed architectural theorist Oscar Newman’s influential 1973 book, Defensible Space. Newman believed that criminal and generally irresponsible behavior was facilitated by (typically modernist) “anonymous public spaces”—large disassociated corridors where it was impossible to tell residents from intruders. He advocated, instead, for buildings that would give residents a feeling of ownership and control. Whether or not one takes strangers as intruders or acclaimed activist Jane Jacobs’s watchful “eyes on the street,” these strategies have slowly fought their way into urban planning and policy.

Much of the contemporary discourse on urban design is rooted in acclaimed architectural theorist Oscar Newman’s influential 1973 book, Defensible Space. Newman believed that criminal and generally irresponsible behavior was facilitated by (typically modernist) “anonymous public spaces”—large disassociated corridors where it was impossible to tell residents from intruders. He advocated, instead, for buildings that would give residents a feeling of ownership and control. Whether or not one takes strangers as intruders or acclaimed activist Jane Jacobs’s watchful “eyes on the street,” these strategies have slowly fought their way into urban planning and policy.

Although problems of concentrated social disadvantage are more complex than any theory of space can account for, many policy makers, city councils and urban management have distilled Newman’s words into one idea: that certain activities can be ”designed out” of public (and private) spaces. And so can certain people.

This approach has developed to the extent that today we have whole industries focusing solely on products that keep out unwanted behavior, activities, and people. From the perspective of property owners and city administration, it might seem convenient to outsource caretaking of the space to architecture itself, a trend that requires no additional costs and no supervision: designers prevent unwelcome uses of areas and features with specifically-engineered shapes, materials, or other features.

Take the famous anti-loitering Mosquito device, which emits an annoying sound only younger ears are able to hear, or the numerous anti-pigeon deterrents (see also our case study of anti-pigeon design). Probably the most infamous recent example has been the use of so-called anti-homeless spikes outside supermarkets in the United Kingdom. Although spokesmen for the British market chain Selfridges have claimed the spikes were meant to reduce litter, the forbidding studs have clear implications for anyone looking to sleep beneath the store’s protective ledges.

It hasn’t always been this way. In the 1980s, New York’s city council was advised by William H. Whyte, author of classic architectural tome The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, on how to create inclusive and pleasant “spaces that work.” Whyte’s guidelines were in turn used to create incentives: developers who provided publicly accessible space were rewarded with more floor space or higher building permits. Whyte saw no problem in having a homeless person share the space with an office worker—to the contrary, he advocated diversity of urban experience and occupancy.

More than a decade into the war on terror, however, this goodwill has mostly disappeared.

We feel increasingly threatened by the “other,” a fear that has influenced even seemingly innocuous public objects like public dustbins. The need to defend our cities from the homeless, the poor, the “antisocial” youth, the feral animals, etc. has escalated as well.

Skaters are growing more and more unwelcome everywhere outside skateparks, while storefronts are featuring dubious installations that prohibit sitting or sleeping. In at least one British mall, hoodies have been banned because they interfere with automated surveillance systems. In short, contemporary urban space is becoming micro-zoned for singular use-scenarios only.

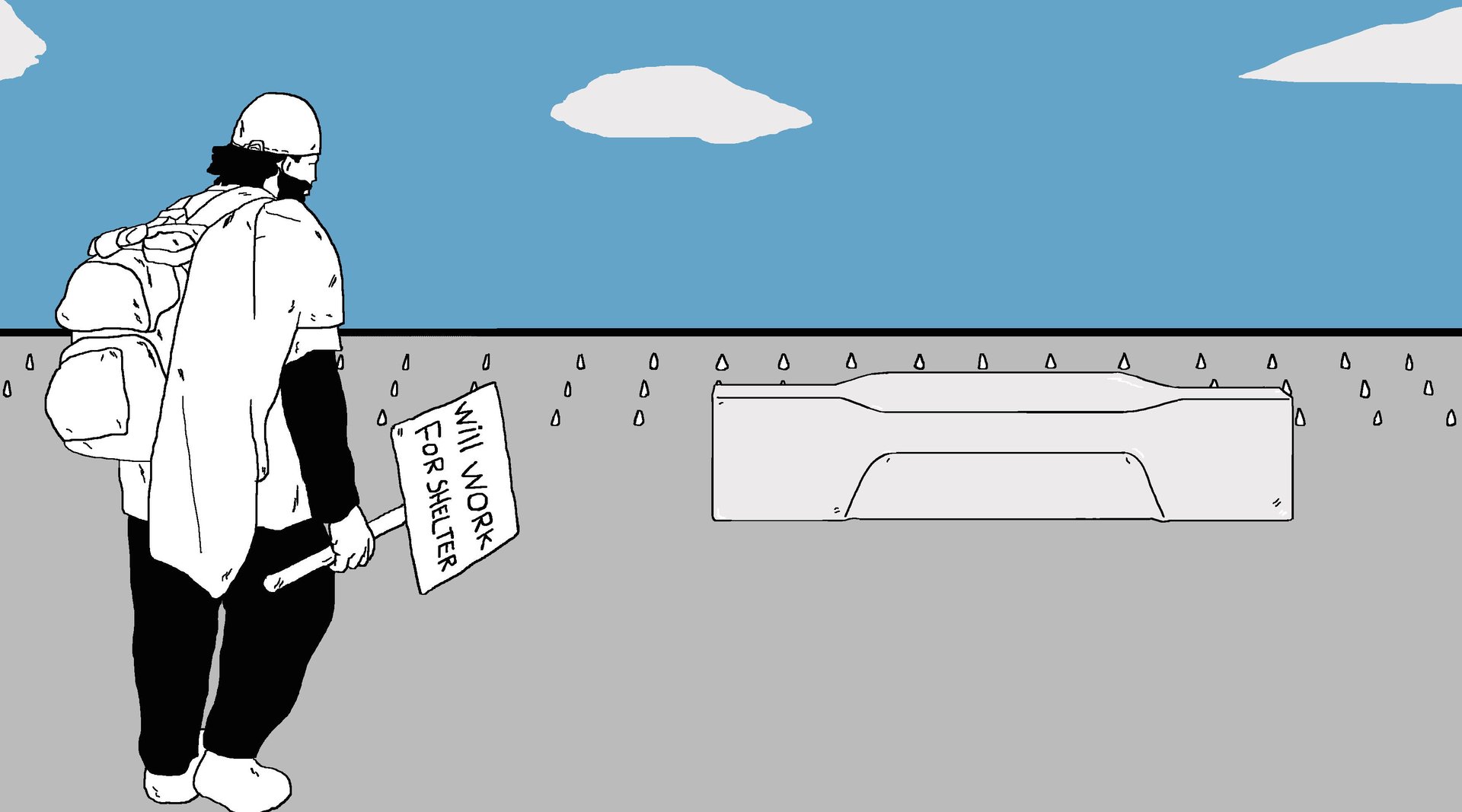

A great example of this singularity of purpose is the London-designed Camden bench, which claims to incorporate 28 different contemporary street seating needs—most of which actively resist any behavior not related to sitting. Created in the name of “inclusive design,” these benches are supposed to encourage social interaction. Yet as a result, skating, hanging out (loitering), littering and of course sleeping is made impossible. Who, or what, benefits from this “inclusive” design?

Vulnerable homeless communities seem to be most at risk. While the latest anti-homeless installation in Selfridges, Manchester, caused widespread outrage, it is only one of many examples of such installations around the world. In June 2014, anti-homeless studs were installed in a London apartment block in Southwark Bridge Road. These were removed six days later by the developer following pressure from London’s mayor Boris Johnson among others. Around the same time, spikes were also removed from a Tesco storefront.

What is interesting here is the shifting idea of what is “acceptable.” Anti-homeless spikes have been used for quite some time, as documented by numerous city activists like Survival Group’s Anti-Sites. But nobody objected until pictures of the installations went viral on social media, prompting mainstream media outlets like the Guardian article to pay attention.

This is the brilliance of good defensive architectural design—it’s easy to miss unless you are part of the community being targeted.

The mainstream media is ultimately not catering to the types of vulnerable populations defensive mechanisms most often focus on. Still, the good news is that more and more people seem unwilling to allow these populations to be punished and marginalized by the sidewalks and benches that make up their cities.

Ultimately, unpleasant design or defensive architecture doesn’t defend us from real threats: a systematic decay of privacy and anonymity in public interactions; overall surveillance and tracking; misuse of meta-data and other types of private information; structural threats to civil liberties through coupling of private interests and weak public institutions. These are the real threats to our society today.

As evidenced by the anti-homeless spikes backlash, people can affect change if they are willing and able to harness their collective power. So far, such attention has been both short-lived, and uninformed by historical and sociological precedent. This is why it is necessary to foster an educated approach to urban design, noting these examples and learning from them. “What attracts people is other people,” Whyte wrote. The least we as architects can do is to try to design pleasant spaces for people to share.