Despite two bad choices, Nigeria’s voters have reason for hope

As it goes to the polls today, Nigeria may superficially seem, as Western observers are so fond of saying, on the brink.

As it goes to the polls today, Nigeria may superficially seem, as Western observers are so fond of saying, on the brink.

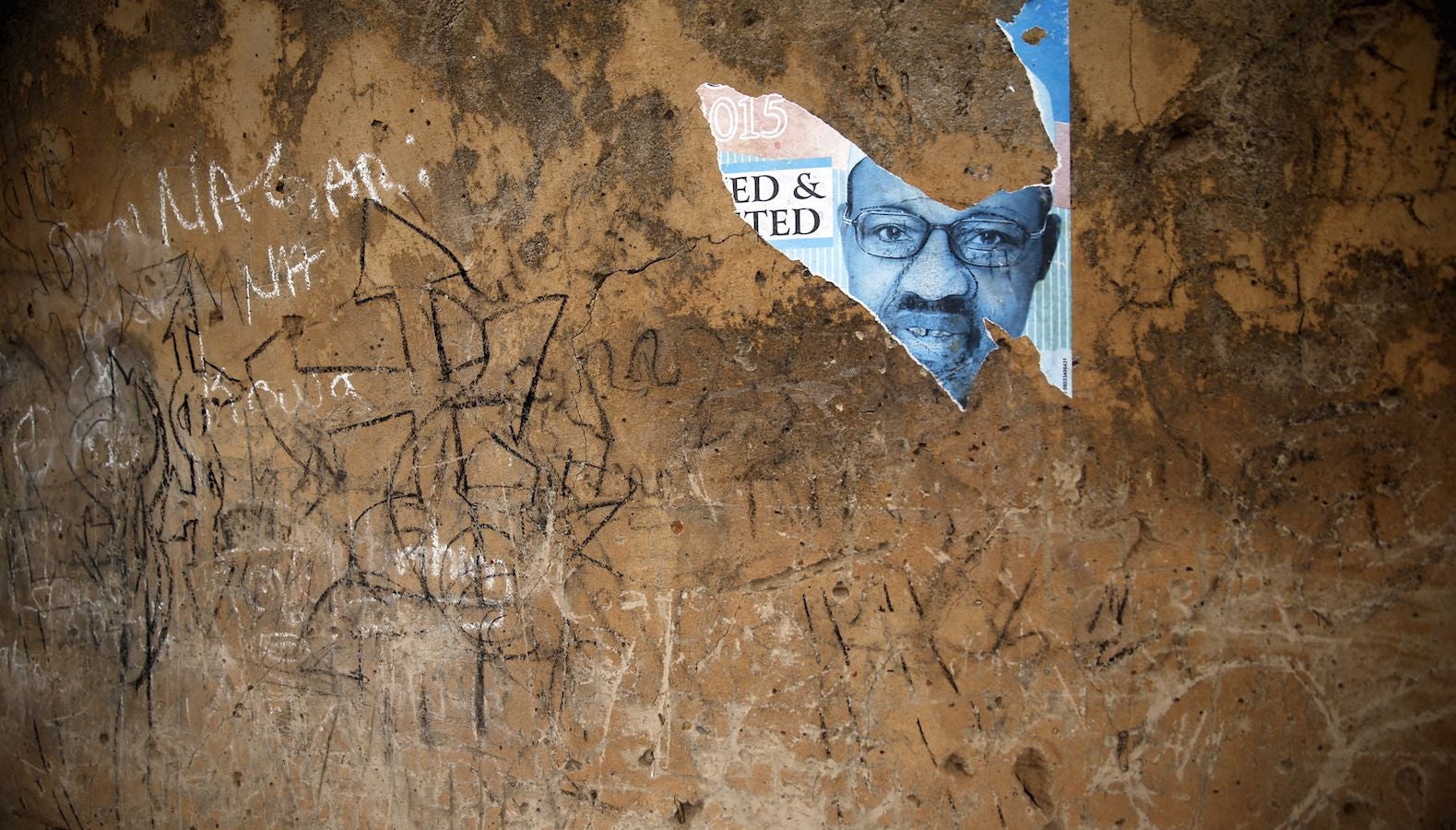

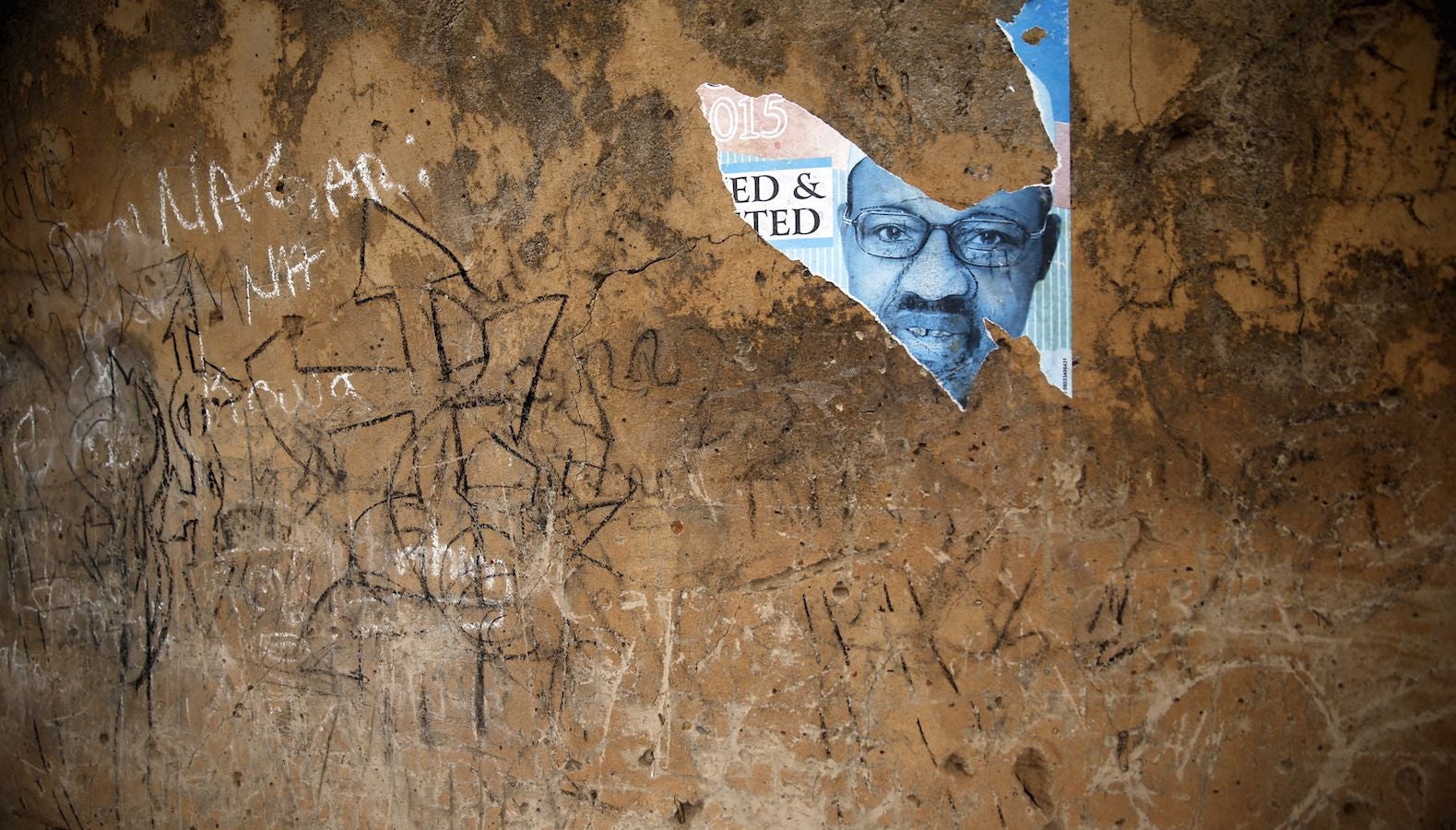

The country’s 69 million voters are nearly evenly split between two bad choices. Incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan has seen the Boko Haram insurgency in the north achieve unprecedented power and levels of brutality on his watch (the Islamists may have kidnapped up to 500 women and children just this week), and his government’s corruption has shocked a populace that thought itself inured to its leaders’ pilfering. The challenger, Muhammadu Buhari, headed a brutal 20-month long military dictatorship in the 1980s which curtailed press freedom, locked up hundreds of people without trial, and had soldiers whipping civilians on the streets.

In personality, the two men are quite different. Jonathan comes across like someone with whom you might like to share a drink at a local beer parlor; Buhari, an ascetic disciplinarian, is more like the headmaster who’ll come round and confiscate the beers. On policy, it’s generally assumed that Buhari would be more effective against both Boko Haram and corruption. But with oil prices plunging (Nigeria relies on oil for 90% of its foreign reserves) and the naira dropping, whoever takes the helm will have difficult job.

As we’ve argued, however, Nigeria is a lot more resilient than it seems. And the bright spot of this election is that it is the first time an incumbent Nigerian president is in any danger of being voted out of power. Public debate is also rowdy and vibrant.

The big risk of instability will be if one man is perceived to have stolen the election. The actual outcome, in some respects, matters less. Whoever wins will, after all, do only a middling job at best.

This was published as part of the Quartz Weekend Brief. You can sign up for our email newsletters here.