Glass architecture is killing millions of migratory birds

Starting this week, a dedicated gang armed with flashlights and Ziplock bags will be roaming the streets of Washington DC. Braving spring’s early morning chill, the 20-plus volunteers who signed up for Lights Out DC will comb a four-mile route for birds that crashed into windows and glass buildings overnight. Working in pairs, the participants typically start at 5:30 am and work efficiently to beat the street sweepers and janitorial crews who power-hose the sidewalks in the US capital.

Starting this week, a dedicated gang armed with flashlights and Ziplock bags will be roaming the streets of Washington DC. Braving spring’s early morning chill, the 20-plus volunteers who signed up for Lights Out DC will comb a four-mile route for birds that crashed into windows and glass buildings overnight. Working in pairs, the participants typically start at 5:30 am and work efficiently to beat the street sweepers and janitorial crews who power-hose the sidewalks in the US capital.

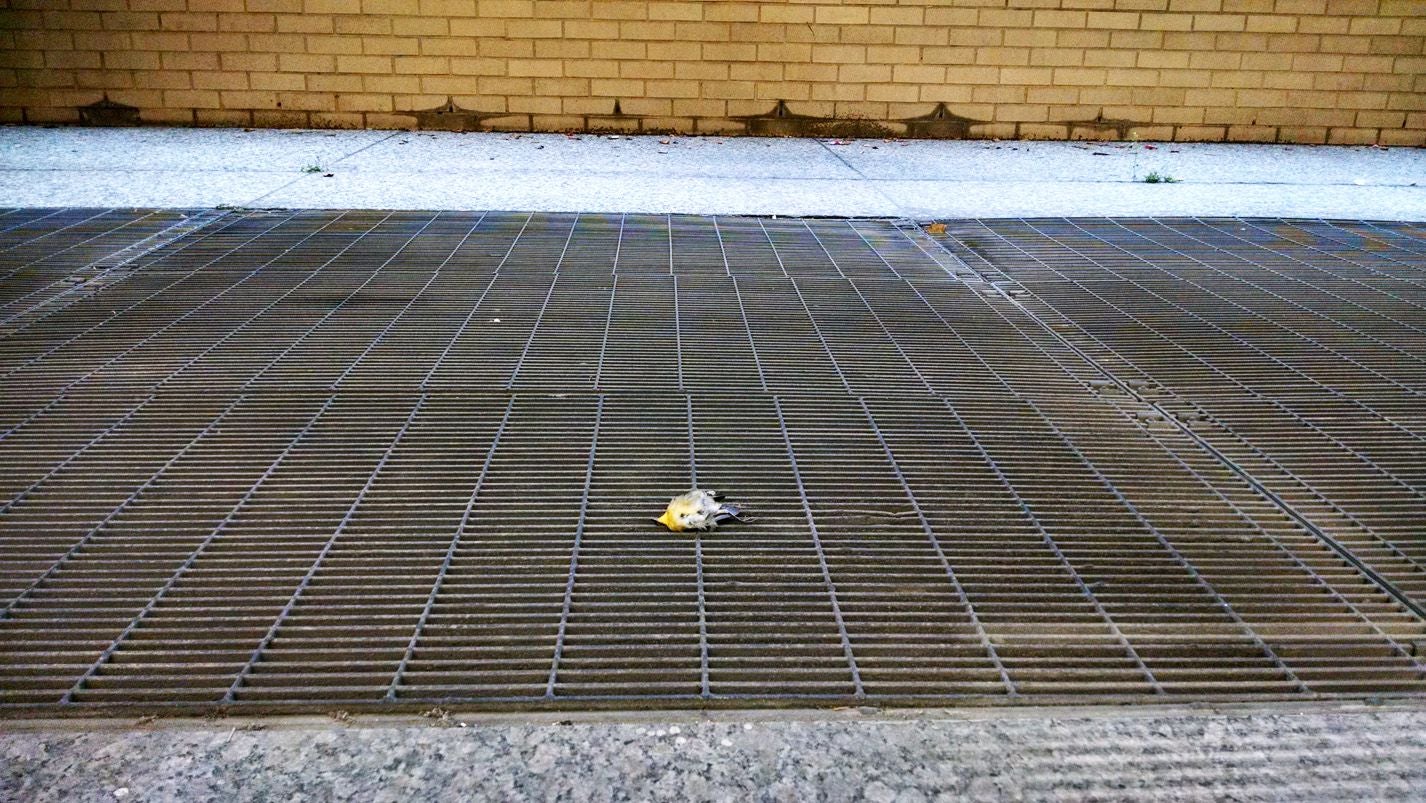

“I play a mental game called ‘trash or bird’,” says Kay Garcia, an illustrator who has been volunteering with Lights Out since 2013. “They’re actually harder to see than you think,” she says.

Most casualties are small—sparrows, starlings, warblers, and wood thrushes (which happens to be Washington’s official bird). Twice a year during spring and autumn, millions of birds travel thousands of miles, tracing ancient routes or flyways in search of fertile feeding and nesting grounds. Smaller birds are night owls, so to speak, and like to travel at night when the air is calmer, relying on stars in the sky for navigation.

Flocks of birds end up in populous urban environments like Washington dense with glass buildings and towers that pepper the skyline. Frequently, birds are lured by artificial lights or become disoriented by smooth, transparent surfaces and slam right into the glass. Most die on impact; those that are maimed often fade overnight before the Lights Out crew can come to their rescue.

Top 10 sites for bird strikes in Washington DC (2013)

Lights Out DC, 2013

According to a study by the USDA Forest Service, about 1 billion migratory birds perish each year due to collisions with windows and lighted structures.

Spot, tag, bag

Each finding is treated like the most tender of crime scenes. The birds are photographed, picked up by hand, tagged, and carefully placed in a plastic bag. The volunteers store them for annual submission to the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, which receives the birds for study. Except for a few species like domestic pigeons and rock doves, all migratory birds are protected under the Migratory Treaty Bird Act, which makes it illegal for anyone without a permit to possess, trap, or trade them—whether the birds are dead or alive.

“I usually keep the birds in the freezer at work during the day,” says Garcia who once dreamed of becoming an ornithologist. How does it feel to hold a dead bird? “It’s a great privilege,” Garcia says. “I mean, when else are you going to hold a yellow-shafted flicker in your hand?”

Fatal attraction

Among the deadliest sites in Washington is a federal building designed by the modernist architect Edward Larrabee Barnes. The building, the Thurgood Marshall Federal Judiciary Center in Northeast Washington, features a five-story glass atrium that showcase live, tall trees in the lobby. Beautifully illuminated at night, it’s heralded as one of the city’s prettiest government buildings—so pretty that its see-through lobby attracts birds with the promise of foliage, only to foil them with the reinforced architectural glass. The building’s management has been cooperating with Lights Out and now dim its lights during the migratory seasons. The intervention is estimated to have reduced avian fatalities by two-thirds.

One of the DC’s ugliest buildings, TechWorld Plaza on 800 K Street, NW, is another killer site. The mirrored connecting bridge that reflects the sky at daytime, and the lights at night, confuses the birds’ orientation and impedes their fly space.

Bird-friendly architecture

Though new buildings aren’t being designed specifically to prevent bird strikes in Washington, there are signs that architects are becoming more attuned to the matter—among them, KieranTimberlake Architects in Philadelphia.

In its design of the new US Embassy in London, KieranTimberlake incorporated an “outer envelope“ in the façade that prevents birds from flying into the glass.

Studio Gang, led by former MacArthur fellow Jeanne Gang, also has been showing a particular sensitivity to the issue. With its undulating profile, the firm’s Aqua Tower in Chicago is a popular totem of bird-friendly architecture (pdf). The 82-story building features wavy balconies that interrupt its smooth, reflective surface and provide the birds a perch.

It’s a global problem

Lights Out DC’s mission may seem simple: Collect compelling evidence to convince building managers to turn off or reduce the lights during migratory season.

But it hasn’t been so easy. Keeping the lights on often is a matter of public safety or practicality, with janitorial crews needing the lights to work, for example. Accurate data collection also has been a challenge for the volunteer-driven organization. But according to Anne Lewis, president of City Wildlife, which runs Lights Out DC, the biggest challenge is a lack of public awareness or understanding.

Lewis tells Quartz that most people “are still unaware that bird strikes are not an isolated event, but rather part of a global problem that results in significant numbers of bird deaths. Everyone who has ever heard or seen a bird strike thinks of it as a very sad, isolated event, not worthy of any corrective action.”

Lights Out DC (pdf) is part of a larger network of citizen groups that protect migratory birds. In Toronto, for example, where the movement first started in 1993 with the Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP), more than 65,000 birds representing 116 species have been collected.