These are the iconic American movies that influenced “Mad Men”

As the hive mind of the TV-watching public excitedly awaits the new season of AMC’s meticulously crafted hit, Mad Men, it must also prepare itself for a sad reality: The seventh season, which debuts April 5, will be the show’s last.

As the hive mind of the TV-watching public excitedly awaits the new season of AMC’s meticulously crafted hit, Mad Men, it must also prepare itself for a sad reality: The seventh season, which debuts April 5, will be the show’s last.

To commemorate the show, Matthew Weiner, its creator, has gotten together with the Museum of the Moving Image in New York to screen a ten-part series of classic movies that he says inspired him when he was writing the script.

The movies, mostly released in the late 1950s and 1960s, include famous Hitchcock classics, but also the French New Wave’s Les Bonnes Femmes, the romantic comedy Dear Heart, the black comedy set during World War I, The Americanization of Emily, the office melodrama Patterns, and male angst drama, The Bachelor Party.

Each is very different, but they all speak to some of the universal themes explored by the show and its complicated protagonist Don Draper, the sinful everyman, the difficult hero: Corporate culture, suburbia and capitalism, gender politics and relationships and the complexities of identity.

Four of them— Blue Velvet, Vertigo, North by Northwest and The Apartment—are iconic American films. If you’re tempted to delve deeper into Draper’s world, line up those martinis, and watch these first. Here are some of the connections to look out for:

Blue Velvet, David Lynch, 1986

First, a non-obvious inspiration. David Lynch’s eerie, creepy classic starring Kyle Maclachlan, Laura Dern and Isabella Rossellini reminds most of his later show Twin Peaks rather than the glossy Mad Men. But, the movie and the show share dream-like moments, and a highly stylized character. Blue Velvet’s iconic opening and closing shots feature the eponymous white picket fence, the symbol of suburban, middle class achievement–examined so thoroughly in Mad Men.

Weiner calls Blue Velvet “indefinable in genre,” with elements of murder mystery, film noir and black comedy. “With stylistic richness and psychological complexity, it celebrates the horror of the mundane and is filled with reference to a kitschy and ironic ’50s’ milieu,” he says in his introduction of the movie for the Museum of the Moving Image. It “became an inspiration for the series and its attempt to equally revise our mythical perception of the period.”

Vertigo,

Alfred Hitchcock, 1958

Enter Hitchcock, and his precision, beautiful cinematography, and play on identity. On Weiner’s list of ten movie inspirations for Mad Men, two are Hitchcock’s masterpieces. About the famous thriller featuring Kim Novak and James Stewart, Weiner says: “I was overwhelmed with its beauty, mystery, and obsessive detail.” This same “obsessive” attention to accuracy is a badge of honor for Mad Men, where copious amounts of research went into everything from costumes to period language.

“I remember watching the camera dolly in on Kim Novak’s hair and thinking, ‘this is exactly what we are trying to do.’ Vertigo feels like you are watching someone else’s dream.” Weiner repeatedly puts his viewers in an otherwordly realm in Mad Men, with dreams, drug trips and flashbacks. As one reviewer wrote: “Mad Men smashes history, desires, dreams, and life’s mundanity together like Douglas Sirk’s Large Hadron Collider.”

Vertigo, named the “greatest film of all time“ is a story of deception between a man and a woman, much like so many relationships on Mad Men. Both Novak’s character, Madeleine Elster, and Don Draper are not who they appear to be, and navigate life with an acquired identity, deceiving those around them.

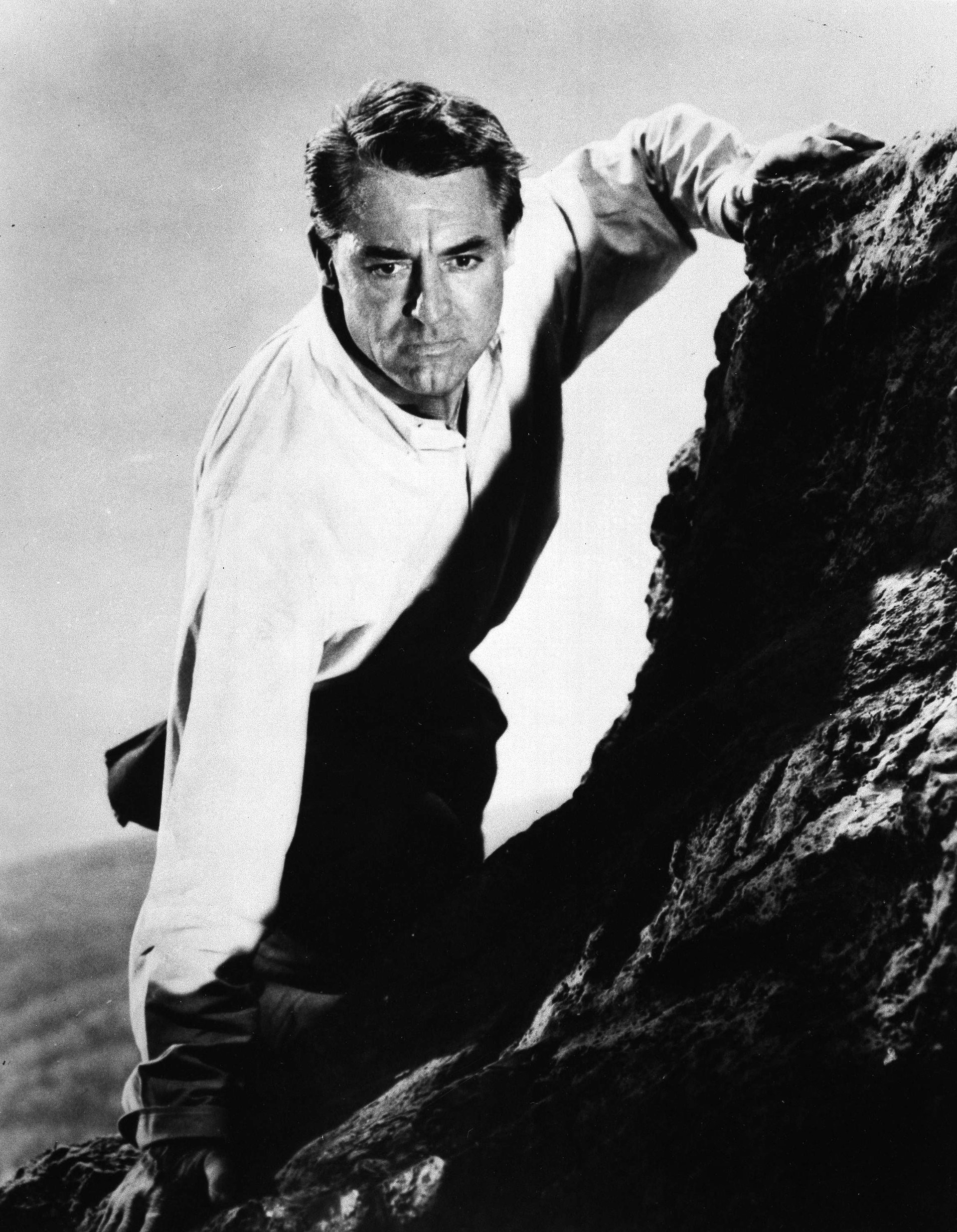

North by Northwest,

Alfred Hitchcock,

1959

Just as he did in Vertigo, Hitchcock bases his intrigue in North by Northwest on a case of mistaken identity. Cary Grant’s character in Hitchock’s action-packed thriller North by Northwest, Roger Thornhill, could be a blueprint for the character of Jon Hamm’s Don Draper. The dashing Thornhill physically resembles Draper, with his tall posture, dark hair, deep voice—and perfect suit. He is charming, a womanizer, and an advertising executive.

“This film became an important influence on the pilot because it was shot in New York City, right around the time the first episode takes place,” Weiner says. “While more overtly stylized than we wanted to imitate, we felt the low angles and contemporary feel were a useful reflection of our artistic mindset.”

The Apartment, Billy Wilder, 1960

Mad Men provides such an indelible illustration of the day’s workplace culture and dynamics, that president Barack Obama mentioned the series in his 2014 State of the Union speech, when speaking of wage equality. “It’s time to do away with workplace policies that belong in a Mad Men episode,” he said. Billy Wilder’s office dramedy The Apartment–in many instances a knee-slapping comedy whose humor still holds up today–shows some of the beginnings of contemporary office culture. ”Corporate reality was becoming a bigger and bigger part of everybody’s lives and Manhattan was the center of it,” Weiner said when introducing the film at the Museum of the Moving Image.

The Apartment shows the devastating effects of the power disparity between male bosses and women working at the lowest rung of the corporate ladder. The relationship between the suave boss in The Apartment and Shirley MacLaine’s elevator girl could be the office affairs of Joan, Peggy or Megan. Weiner said the movie was “scandalous” at the time, which “treated infidelity as a kind of foreign disease.” Weiner added, “Mad Men wasn’t supposed to be an imitation of this, but this was the movie that the people at the time saw.”