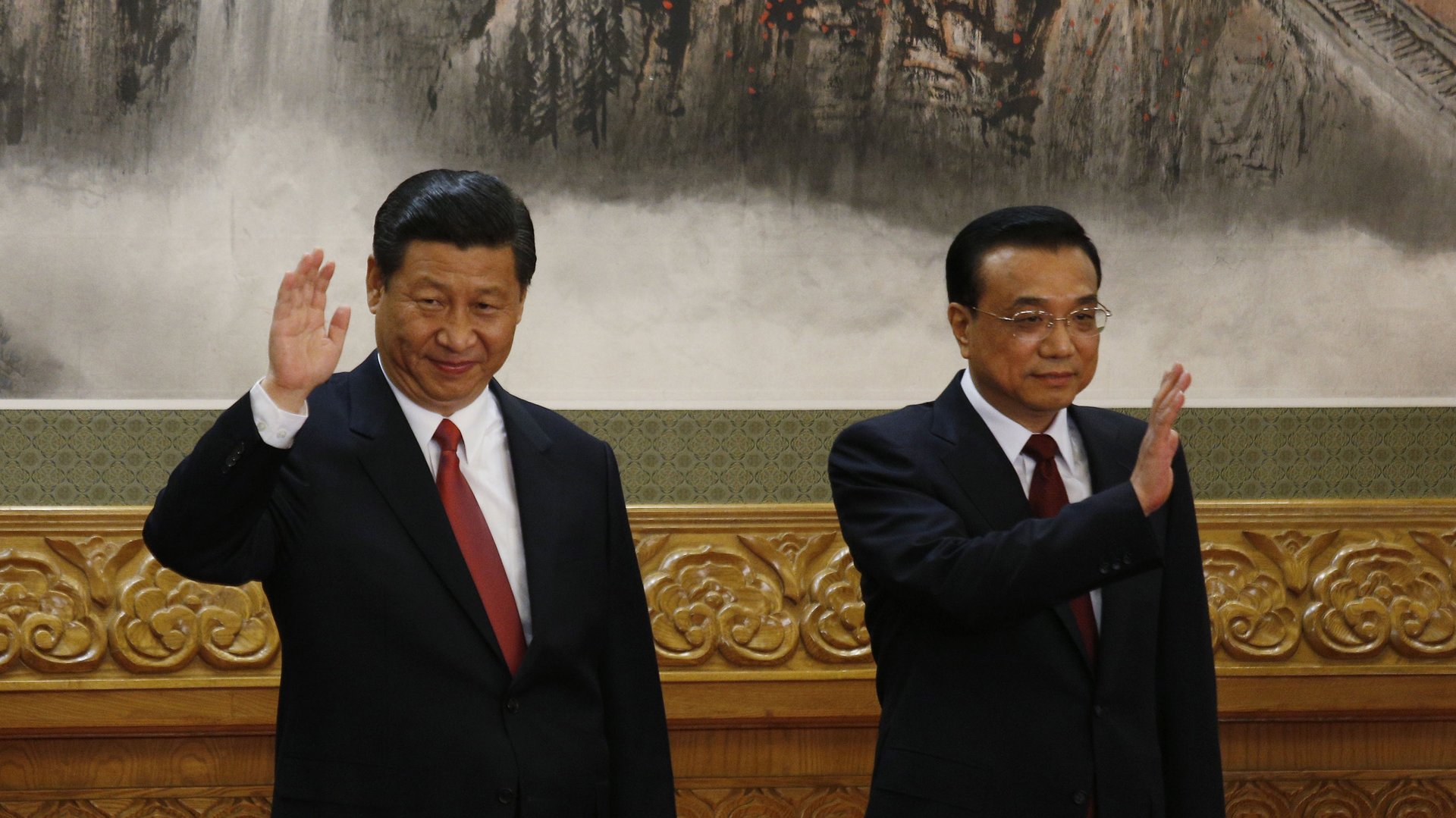

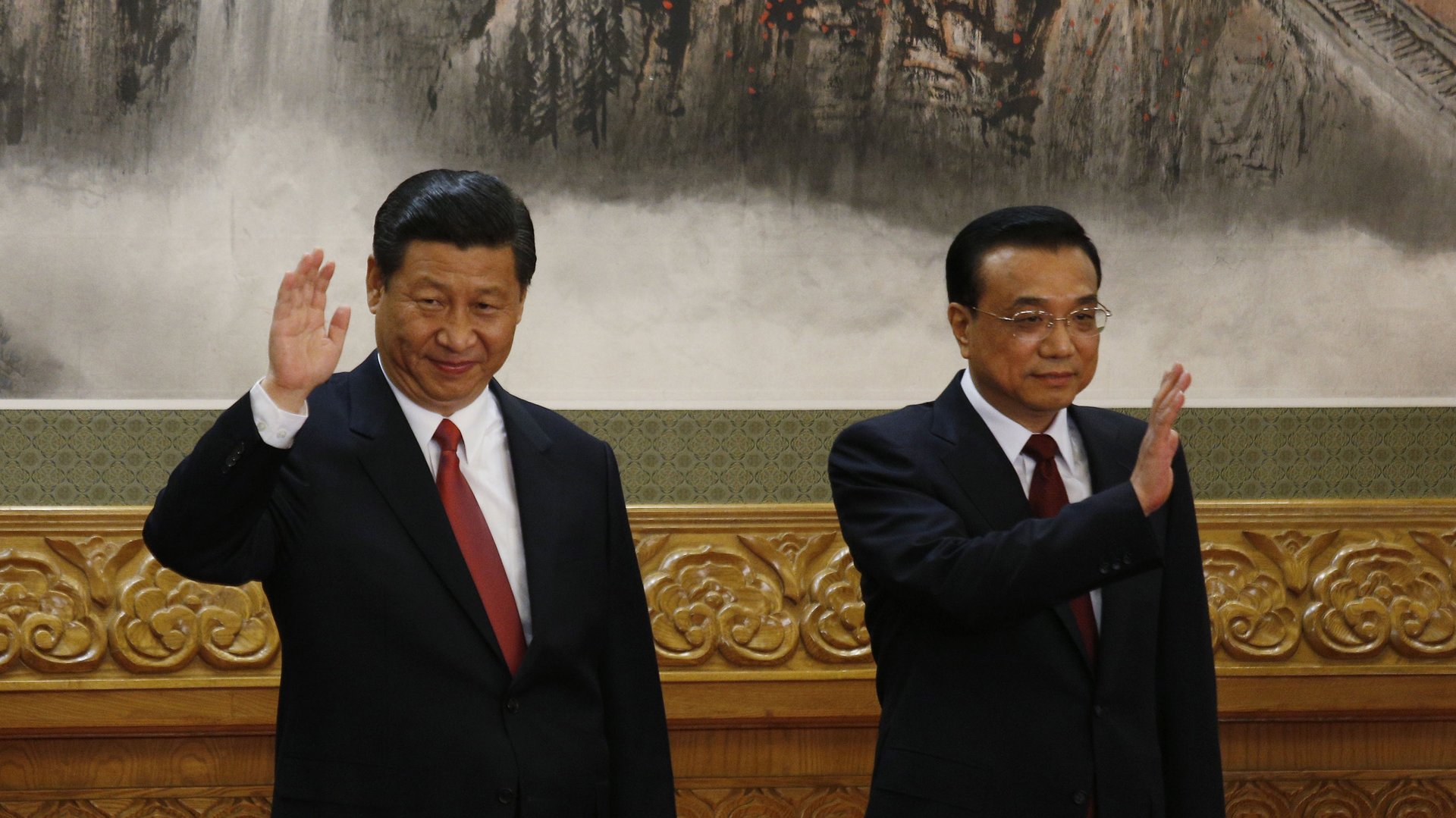

Reading the tea-leaves of the first economic planning meeting for China’s new leaders

China’s annual meeting to set the national economic agenda, known as the Central Economic Work Conference, wrapped up on Dec. 16–with results that will disappoint anyone hoping for a bold vision from China’s new leaders, Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang. Though the conference has never been a platform for broadcasting dramatic policy shifts, this year’s unusually vague and conservative conference report (in Chinese) signals that China’s new leaders are likely to prioritize caution over effectiveness in their new tenure.

China’s annual meeting to set the national economic agenda, known as the Central Economic Work Conference, wrapped up on Dec. 16–with results that will disappoint anyone hoping for a bold vision from China’s new leaders, Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang. Though the conference has never been a platform for broadcasting dramatic policy shifts, this year’s unusually vague and conservative conference report (in Chinese) signals that China’s new leaders are likely to prioritize caution over effectiveness in their new tenure.

The major break with past themes was this year’s emphasis on improving social welfare and living standards, while downplaying the focus on growth that featured so heavily in past reports. This shift is all the more surprising given that the report also spelled out, far more explicitly than in the past, the “downward pressure on economic growth” that China now faces. Indeed, this year’s report alluded several times to concerns about “excess capacity” (channeng guosheng) concerns, as well as to worries about redundant public infrastructure investments.

For those worried that the government may pull the plug on infrastructure spending, the familiar refrain of “urbanization” (chengzhenhua)—something the conference has championed every year in recent memory—and its continued promotion of “proactive” fiscal policy should quell such fears. However, the report’s emphasis on social welfare suggests that the government’s past obsession with high growth might at last be taking a backseat to longer-term economic goals.

And how might those priorities be achieved? Unclear. Beyond looking to lead the masses to adopting the concept of “self-made wealth” (qin lao zhi fu), the report declines to mention any details of its reform agenda—an omission that elicited (link in Chinese) disappointment from some quarters of the Chinese media. One such hoped-for reform was a property tax; after last year’s report mentioned the idea for the first time, its absence from this year’s report leaves the policy up in the air once again.

In addition, the report offered scanty, if any, detail on addressing the widening wealth gap, notably the controversial “income distribution adjustment” (shouru fenpei tiaozheng) reform. China expert Bill Bishop flags reports that this plan has been delayed yet again.

Despite the report’s lack of specifics, its newfound focus on social issues signals at minimum that the incoming administration’s attention is aimed where it should be: on creating opportunities and social support for its poor and middle-class citizens. And it’s certainly possible that Xi and Li will wait for their official accession in March before rolling out headline policies. But for the moment, those who worry that China’s new leaders lack political clout can comfortably add another item—policy vision—to Xi’s and Li’s list of disquieting deficiencies.