Another perplexing detail emerges in the beepocalypse mystery

The theory that insecticides are causing the “beepocalypse”—the large-scale death of honeybees characterized by worker bees fleeing their hives—suffers from a lot of unknowns.

The theory that insecticides are causing the “beepocalypse”—the large-scale death of honeybees characterized by worker bees fleeing their hives—suffers from a lot of unknowns.

One is that neonicotinoids—the pesticides blamed for the beepocalypse—are likely not the sole cause of ”colony collapse disorder” (CCD), as the phenomenon is known. And in the US, at least, it’s not entirely clear that CCD is still hurting the honeybee industry.

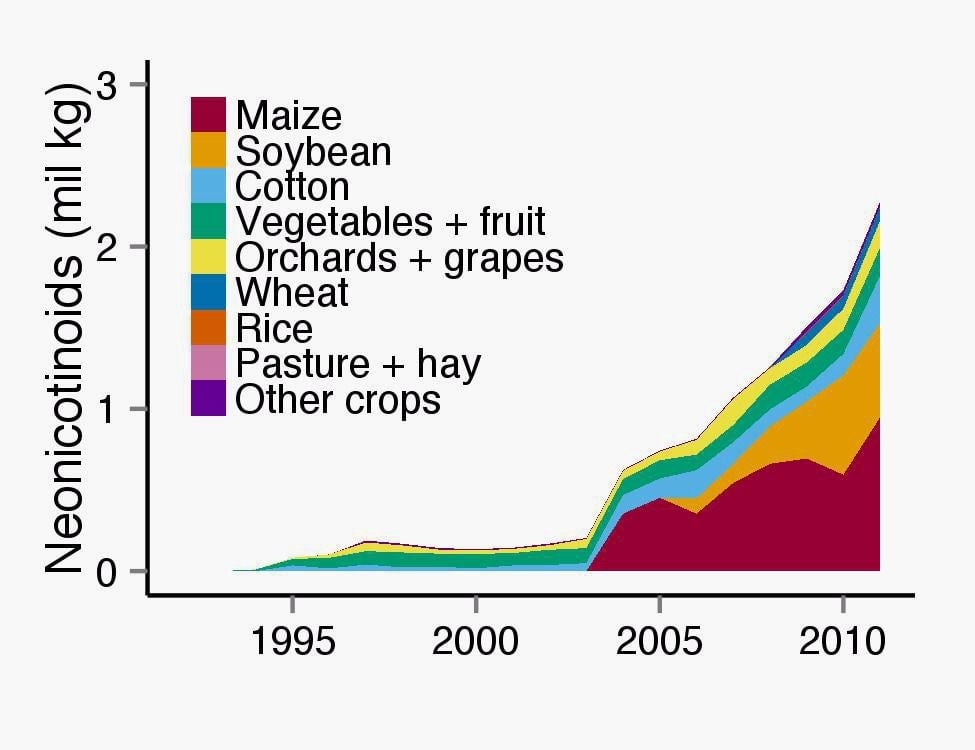

To complicate the matter further, new evidence suggests the US has been using far more insecticides, including neonicotinoids—than government agriculture data have indicated. Here’s a chart:

In 2000, less than 5% of soybean acres and 30% of land planted with corn were treated with insecticide. By 2011, that had jumped to a third and nearly 80% of soybean and corn acres, respectively, according to research published today (paywall) in Environmental Science & Technology.

What the researchers found flies in the face of conventional wisdom on neonicotinoid use, says co-author Margaret Douglas, a graduate student in entomology at Pennsylvania State University.

“Previous studies suggested that the percentage of corn acres treated with insecticides decreased during the 2000s, but once we took seed treatments into account we found the opposite pattern,” says Douglas in a press statement. “Our results show that application of neonicotinoids to seed of corn and soybeans has driven a major surge in the U.S. cropland treated with insecticides since the mid-2000s.”

The big reason that we’ve been oblivious to that dramatic increase is that the US government’s national pesticide survey doesn’t document neonicotinoid use on seeds, which persist in plant tissues for up to several months. To fill in that gap, the researchers analyzed seed data from the US Geological Survey that just became available to estimate the share of corn and soybean land that used neonicotinoid-treated seeds. They then combined it with the non-seed treatment data and back-checked the total against information from the Environmental Protection Agency and the seed supplier DuPont Pioneer.

The strange thing is that this wild surge in US neonicotinoid use doesn’t appear to relate the the risk posed by insect pests, say the authors. The data suggest that farmers are dosing seeds with the chemicals as a sort of “insurance policy” against attack, and not to an immediate threat.

Based on abundant evidence that neonicotinoids harm bee colony health—even if they may not outright cause CCD—the European Union has already suspended their use on bee-related crops. (Bees aren’t the only creatures that suffer. Monarch butterfly numbers hit their lowest levels in 2013-2014. In the Netherlands, neonicotinoid levels in surface water correlate with dwindling numbers of aquatic invertebrates and birds.)

The US government is still debating the risk; a White House task force announced in June 2014 is poised to take action against neonicotinoid use. Knowing how much neonicotinoids farmers are actually using should help ground the debate.