Corporations are the people of the year, my friend

Who’s the most important newsmaker of the year? Time magazine says Barack Obama. We disagree. It’s the American corporation.

Who’s the most important newsmaker of the year? Time magazine says Barack Obama. We disagree. It’s the American corporation.

Ever since Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney reminded us of the legal fiction of corporate personhood during the past summer’s presidential campaign—“corporations are people, my friend!”—we’ve looked at the organizational structure in a new, more personal light. While Time, the popularizers of the person of the year concept, is right that the president dominated 2012, it’s worth remembering this: His term has largely been defined by his efforts to rescue corporations from themselves, and their attempts to fight his policy agenda.

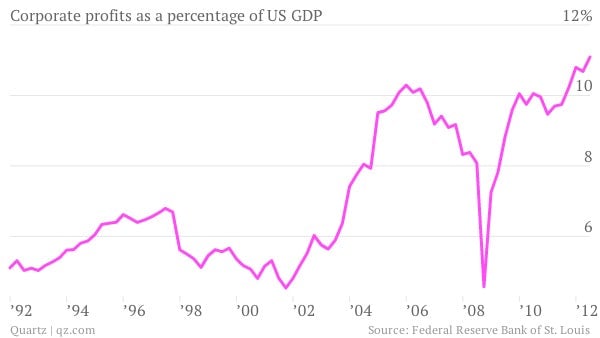

And it turns out corporations have had quite the resurgence in the past year:

What you’re seeing is after-tax corporate profits as a percentage of the US economy, and the the last decade has just been swell for them; record-setting, in fact, despite the crisis. Corporate profits now make up more than one-tenth of the whole economy! This is a highly unusual situation to be in, and well worthy of recognizing.

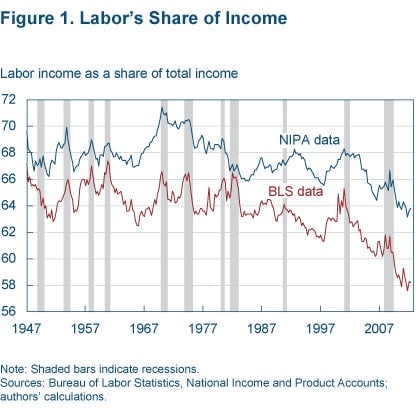

Our case further solidifies with a look at how poorly unincorporated persons have fared in recent years:

That chart comes from this research at the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, which shows the share of national income that goes to workers. It’s a story with many factors, but the overarching theme is that of capital income eclipsing labor income. This is all thanks to high unemployment, which hurts wage growth, the favorable tax treatment of corporations and the income they produce for investors, and advances in productivity that make fewer people capable of doing much more work.

And it’s not just that corporations are competing with real people in the economic environment. They are also doing so in the political sphere, using $1 billion to influence the 2012 presidential election after a Supreme Court decision that removed limits on corporate political spending. The bulk of that money went, appropriately, to support Romney, but though he failed to win, the ads—like this scare-mongering number about China—helped shape the campaign narrative. The SuperPAC funded by Sheldon Adelson’s businesses was almost single-handedly bankrolling the presidential campaign of former House Speaker Newt Gingrich last year, and that’s got to count for something.

Corporations are among the more trusted institutions in our public life: Small businesses and technology companies are the two institutions with the most positive impact, according to Pew Center data, and while large corporations are viewed to have a negative impact, they’re considered more beneficial than the news media and the federal government.

Then there’s the criminal activity. HSBC, the global bank, entered a deferred-prosecution agreement with the US government to settle charges of money-laundering, proving far more robust than people charged with the same offenses.

Time magazine also included two business leaders on its shortlist—Apple CEO Tim Cook and Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer. While both may be talented individuals, they would be nothing without the corporate bodies undergirding their success. Tim Cook is just a stand-in for “the year Apple became the globe’s biggest-ever company” (score another point for corporations) while Mayer’s nomination, well, it’s not yet clear what Yahoo has done under her tenure, but the fact that the internet-era dinosaur still exists is a point in favor of corporate resilience.

Indeed, as global economies struggle for growth, the only institutions showing much adaptability to the world-spanning economy are multinational companies that operate in many jurisdictions, seizing opportunities and extracting value at will. People are limited by their physicality, their mortality and, in some cases, an unwillingness to make quarterly earnings their guiding principle. The corporate person as a globe-spanning abstraction, potentially immortal and amorally efficient, is by far the better symbol of our times.

In awarding our person of the year award to “the corporation,” we hope we have at least made one thing clear: “Person of the year” is a fairly silly analytical concept.