Why I didn’t go to art school—and why everyone does now

Throughout my 20s, I lived in New York and never once thought about applying to art school. Art school, at the time, seemed to be for people who weren’t really intending to become artists. I knew all the artists. I even studied with some. But the tuition—sometimes paid for with money, more often intangibly—never passed through an institution. I paid with a loyalty that was often betrayed. But this is normal.

Throughout my 20s, I lived in New York and never once thought about applying to art school. Art school, at the time, seemed to be for people who weren’t really intending to become artists. I knew all the artists. I even studied with some. But the tuition—sometimes paid for with money, more often intangibly—never passed through an institution. I paid with a loyalty that was often betrayed. But this is normal.

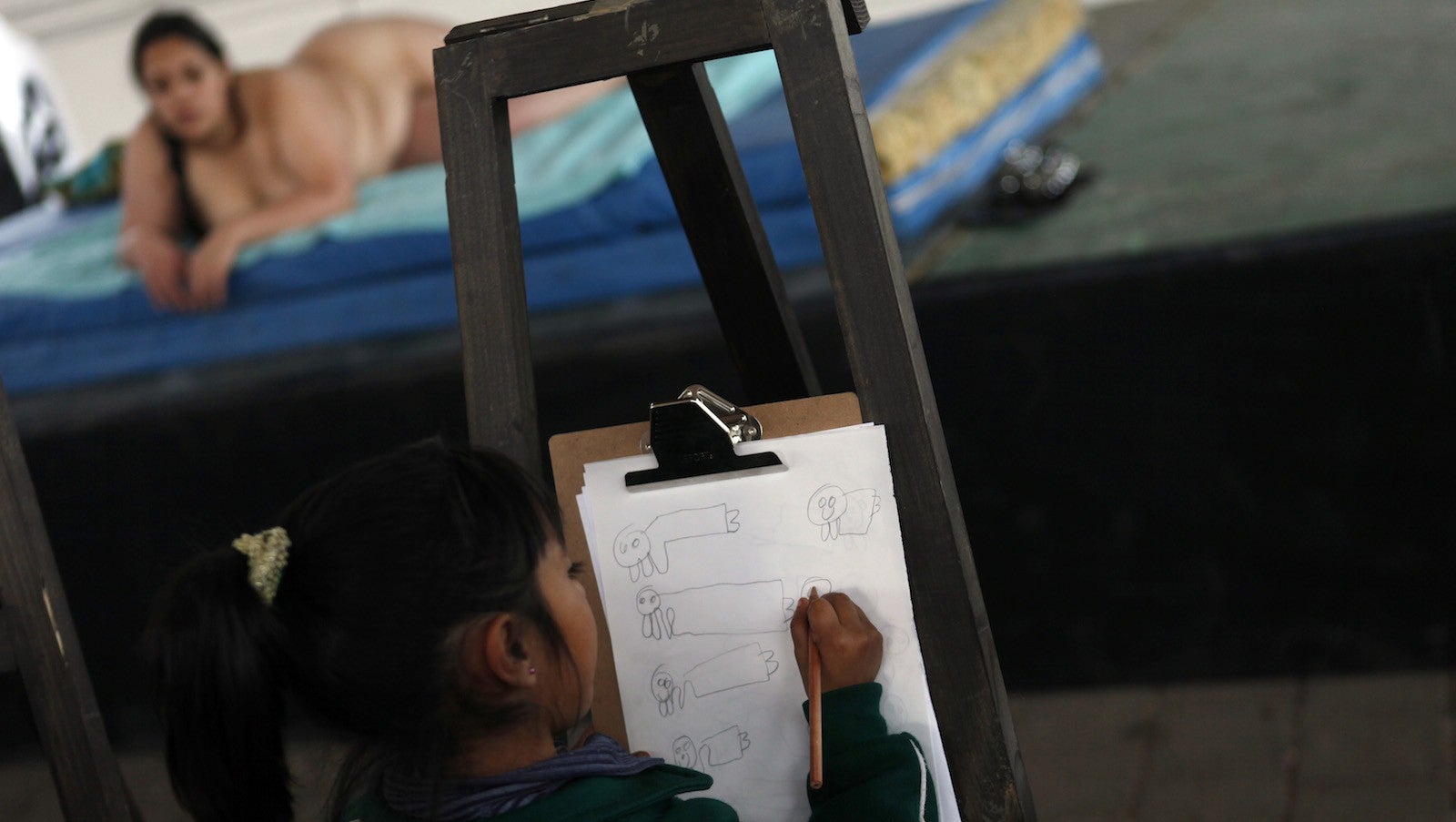

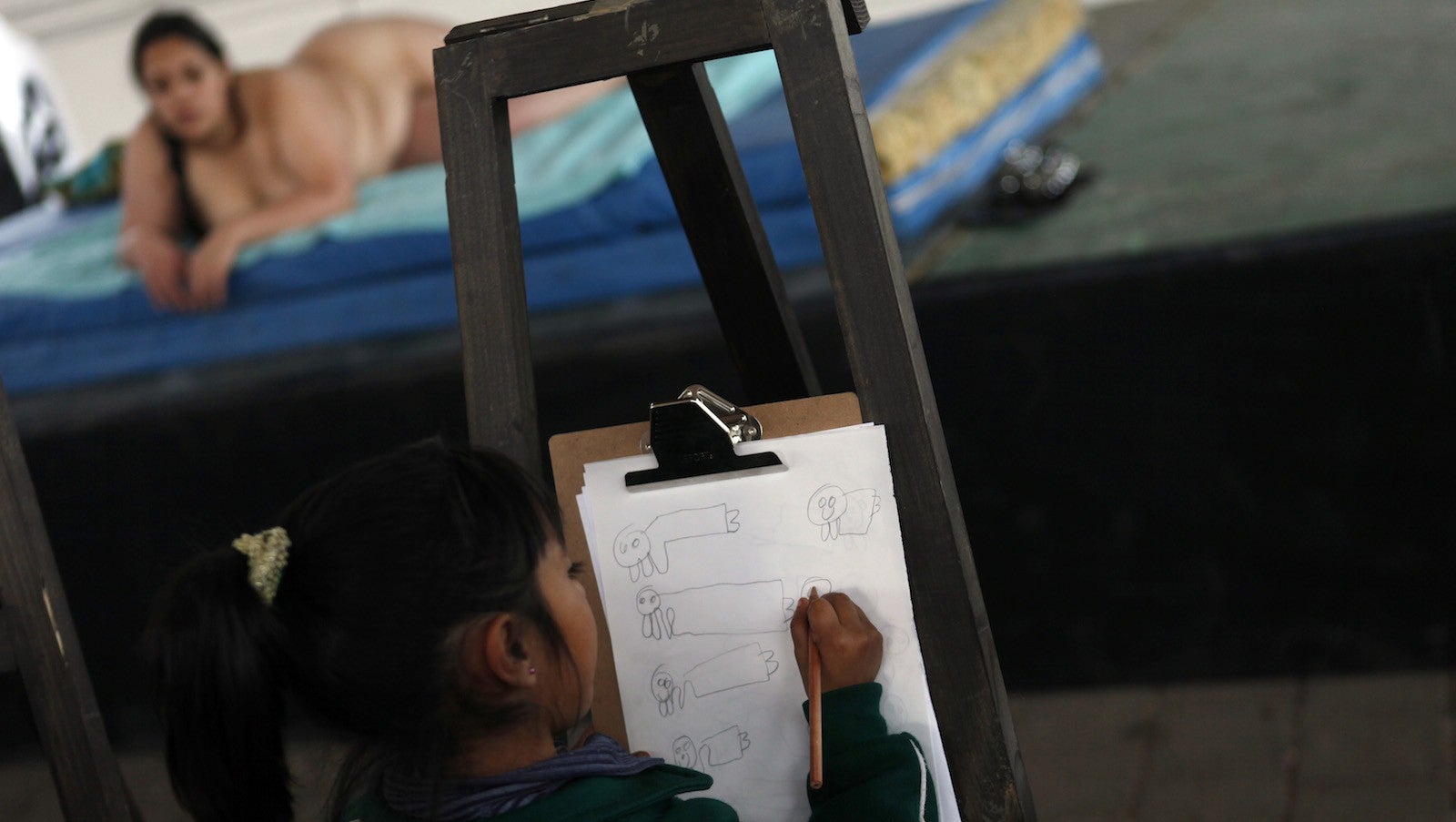

My real education took place in my apartment. Convinced that to be an artist I’d need lots of free time, I did occasional temp work supplemented by low-level scams and some topless dancing.

This gave me lots of free time, but at the time, I didn’t know what to do with it. Sometimes I slept twelve hours a day. I remember looking in the mirror at my too-rested face and realizing the hardest thing I’d have to learn was how to make my own program, how to inhabit unstructured time without getting lost in it. I don’t know if you learn this in grad school.

When, in my late 20s, I began living with a tenured professor at Columbia University, the question of art school, or other graduate school, became tabled. His grad students became my close friends. Before leaving New Zealand in my late teens, I’d unsuccessfully applied to Columbia’s graduate program in journalism. In the end, I attended the school by osmosis.

It’s only at times when I want to escape from my life that I regret not going to art school.

The bios of writers whose careers I envy usually contain the names of the prestigious MFA programmes they attended. If I’d gone to the right MFA programme, I’d have an agent! I wouldn’t be virtually self-published by Semiotexte, the independent press where I’m a co-editor. My writing would be reviewed in serious, adult publications. But in order for these things to happen, I’d have had to write different writing.

As it is, my writing is read mostly within the art world—a field in which virtually everyone attends an MFA programme. And I try not to criticize this. Perhaps for the better, grad school has taken the place of my generation’s aimless experience.

I’ve noticed a trend among students in certain liberal arts undergrad schools to move to New York or Berlin or Los Angeles after Grinnell or Reed College or Swarthmore. Not applying to grad school or art school is very neo-old school. And this is exciting. What will be even more exciting is if the cultural life of these cities approaches a point where alumni of less elite schools can embrace the same mixture of deep disillusion and confidence.

Art and commerce have always been two sides of the same coin and to oppose them would be false. Instead, I want to talk about a shift that has taken place during the past ten years in how art objects reach the market, how they’re defined and how we read them.

The professionalization of art production—congruent with specialization in other postcapitalist industries—has meant that the only art that will ever reach the market now is art that’s produced by graduates of art schools. The life of the artist matters very little. What life? The lives of successful younger artists are practically identical.

There’s very little margin in the contemporary art world for fucking up, accidents or unforeseen surprises. In the business world, lapses in employment history automatically eliminate middle managers, IT specialists and lawyers from the fast track. Similarly, the successful artist goes to college after high school, gets an undergraduate degree and then enrolls in a high-profile MFA studio art programme. Upon completing this degree, the artist gets a gallery and sets up a studio.

When collectors pay ten thousand dollars for a David Korty landscape, they aren’t purchasing a pleasant watercolor of a night sky wrapped around a hill. Other, more naive artists have done these painting more consistently, and may have even done them “better.”

What collectors are acquiring is an attitude, a gesture that Korty manifests through his anachronistic choice of subject matter. The real “meaning” of the work has very little to do with the images depicted in his paintings—night skies wrapped around a hill—or their execution. Rather, the “meaning” (and the value) of the work lies in the fact that Korty, a recent graduate of UCLA’s MFA art programme, would defiantly loop backwards to tradition by rendering something as anachronistic as a landscape in the quaint medium of watercolor. After all, he has all of art history’s image-bank to choose from.

Similarly, when Art Center MA graduate Andy Alexander spray paints the words “Fuck the Police”on the corridor walls of his installation, I Long For The Long Arm Of The Law, the piece is not relegated to the realm of the “political.” Instead, he is praised in a review by Peter Lunenfeld published in Artext for his “subtle aestheticism,” which enacts “a dilation and contraction between psychological and social domains.” Andy Alexander is an intelligent and enthusiastic younger artist. His dad was once the mayor of Beverly Hills.

Interviewed by Andrew Hultkrans in the notorious Surf and Turf article that proclaimed the dominance of Southern California art schools (Artforum, Summer 1998), Alexander expresses his enthusiasm for art school as a place that “teaches you certain ways of looking at things, a way of being critical about culture that is incredibly imperative, especially right now.” Like most young artists in these programmes, Alexander maintains a certain optimism about art: that it might be a chance to do something good in the world.

Yet if a black or Chicano artist working outside the institution were to mount an installation featuring the words “Fuck the Police,” I think it would be reviewed very differently, if at all. Such an installation would be seen to be mired in the identity politics and didacticism that, in the 1990s, became the scourge of the Los Angeles art world.

Writing in the Los Angeles Times in 1996, critic David Pagel dismissed two decades of work by the black British artist/film-maker Isaac Julien exhibited at the Margot Leavin Gallery as “myopic and opportunistic.” “The conservative exhibition,” Page wrote, “contends that the social group the artist belongs to is more important than the work he makes … Art as self-expression went out in the 1950s.” Pagel triumphantly concludes, “even though this show tries to deny it … Market research puts people into categories; art only begins when categories start to break down.”

Whereas modernism believed that the artist’s life held all the magic keys to reading works of art, neo-conceputalism has cooled this off and corporatized it. The artist’s own biography doesn’t matter much at all.

What life? The blanker the better. The life experience of the artist, if channelled into the artwork, can only impede art’s neo-corporate, neo-Conceptual purpose. It is the biography of the institution that we want to read.