The magic number that makes us start collections is two

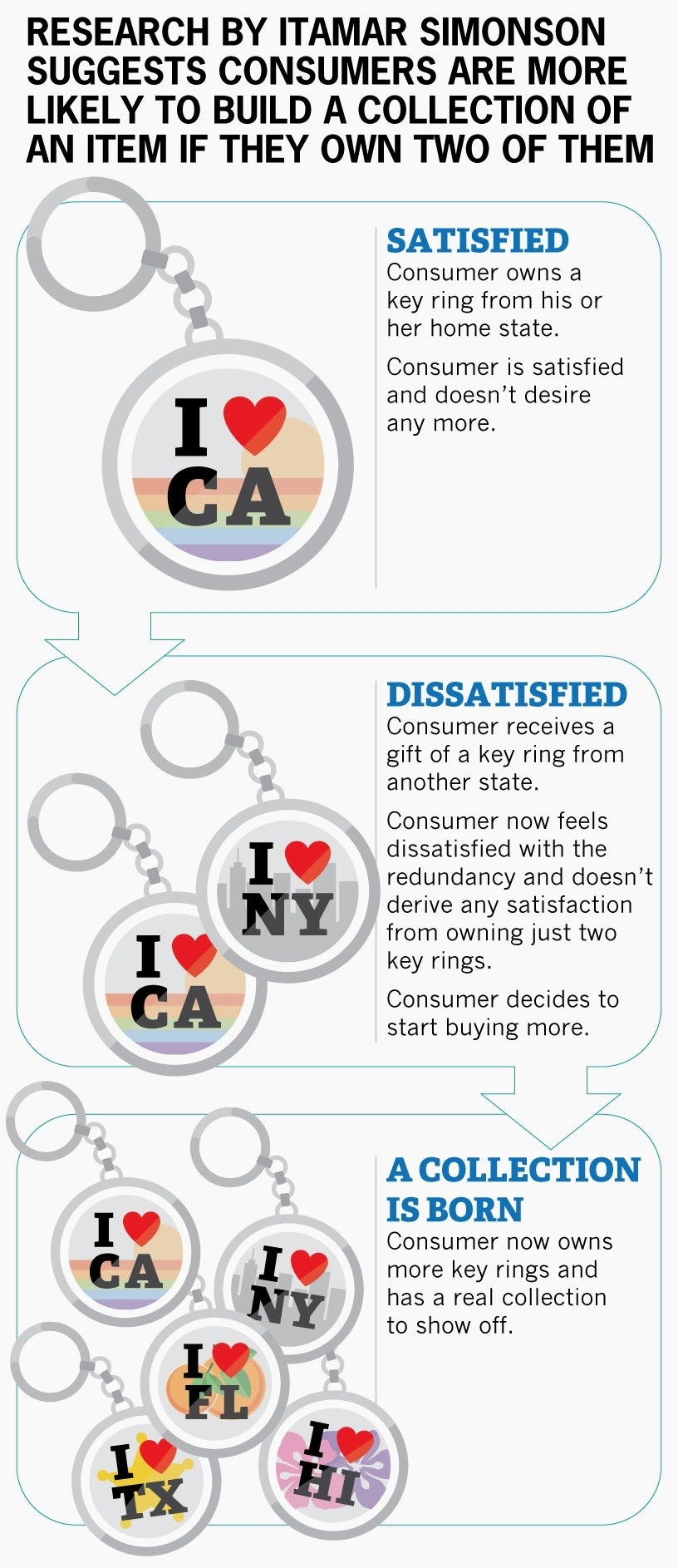

Everyone knows someone who collects things—whether it’s refrigerator magnets or political bumper stickers. But what marks the turning point at which someone goes from owning items to building a collection of them? Research by Itamar Simonson found that it all starts with two: People are more likely to build a collection of something once they possess two of them.

Everyone knows someone who collects things—whether it’s refrigerator magnets or political bumper stickers. But what marks the turning point at which someone goes from owning items to building a collection of them? Research by Itamar Simonson found that it all starts with two: People are more likely to build a collection of something once they possess two of them.

The study, which Simonson, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business, conducted with Leilei Gao of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Drexel University’s Yanliu Huang, challenges long-standing assumptions of what drives consumers to collect. Past research suggested that consumers collect things because they like certain traits, or because they own one of an item and like it enough to buy more. But the researchers found that consumers don’t always make such purposeful and deliberate decisions to start building a collection. Rather, they might do so because they own a couple of the items and feel uneasy about it because they associate it with waste or duplication.

“With one item only, there’s no redundancy, and the thought of collections as a goal does not arise,” says Simonson. Besides, that one item could be a particular favorite and so makes the consumer happy. That all makes owning one “easy to justify,” he says.

But two? That smattering of items is too large to be thrown out but too small to be a genuine collection that brings pride or satisfaction. And from a practical perspective, owning two of anything is “difficult to justify,” according to Simonson. This prompts consumers to remedy the situation by buying more of the product in question. This is the “tipping point,” where purchasers are more likely to buy more to build an actual collection, he says. “We think that consumers don’t like to see things that are wasted, especially when this redundancy is not easily justified,” says Simonson. “They want to pursue and achieve a purpose, such as building a collection.”

The research is particularly relevant to companies that sell collectibles or run collection-based loyalty programs. It also sheds light on consumers’ motivations, suggesting that they like to justify not only what items they own but also how many they have.

In one experiment involving collectible pins, participants possessing two of a collectible line saw the set as “neither here nor there.” They described their feelings with statements such as, “I feel unsatisfied as the collection is incomplete,” “I feel uncomfortable as my position is kind of in the middle of something,” and “The current possession seems less valuable to me if I cannot get more pins.”

During the 2010 FIFA World Cup soccer tournament, the researchers gave 93 students in Hong Kong collectible boxes of mints depicting FIFA soccer teams. Participants received either one or two boxes of mints, and were told that the mint boxes were part of a collectible series. The students were then asked to choose another FIFA mint box or a ballpoint pen of equivalent value. Those who had one box of mints were no more likely to select another box than those in the control group, who received regular, non-collectible boxes of mints. But participants with two collectible boxes were more likely to select a third box than those with one collectible box or just a regular box.

Similarly, in another experiment, 169 students from Hong Kong were more likely to choose a refrigerator magnet over a pen if they had been told that they already had two or three magnets. Those who had only one magnet were no more likely than those with none to choose another magnet.

Results were different for more valuable items, however. The researchers showed each of 337 participants photographs of Coke cans, some deemed collectible and others simply regular cans. Some participants were told that the collectible cans were designed years ago, available for only a limited time, and therefore rare. The rest were told that the collectibles were newly designed and easily purchased.

The researchers found that among those who believed the collectible cans were easily obtainable, those shown two collectibles were more likely to want another than those shown one or no collectible cans. But those who believed the collectible cans were rare were more likely to want another even if they were shown just one can. This suggests that if consumers believe something is rare or valuable, owning even one is enough to make them want more.

But for most collectibles, which aren’t particularly valuable, marketers would be wise to find ways to place at least two in the customer’s hand early on, the researchers note. They could sell or give away two items at a time at the start of a campaign, or discount the second one. And rather than urge customers right away to “build a collection” or “collect all 12,” marketers could encourage them to acquire “the first few” and promote the notion of a large collection later. “McDonald’s may indeed want to include two items, which may trigger a collection and many more Happy Meal sales,” says Simonson.

Itamar Simonson is the Sebastian S. Kresge professor of marketing at Stanford Graduate School of Business. “The Influence of Initial Possession Level on Consumers’ Adoption of a Collection Goal: A Tipping Point Effect,” was published in November in the Journal of Marketing.