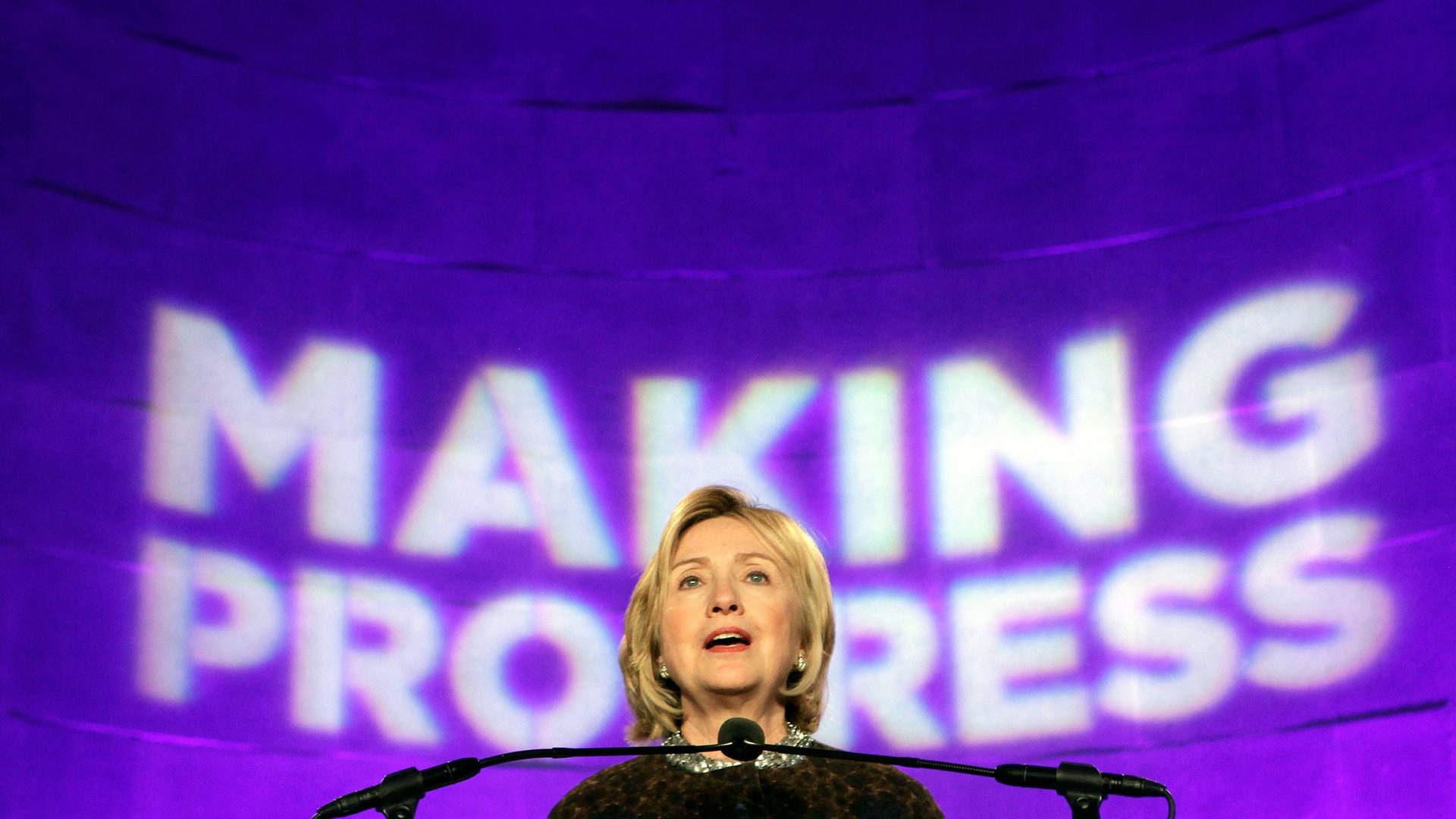

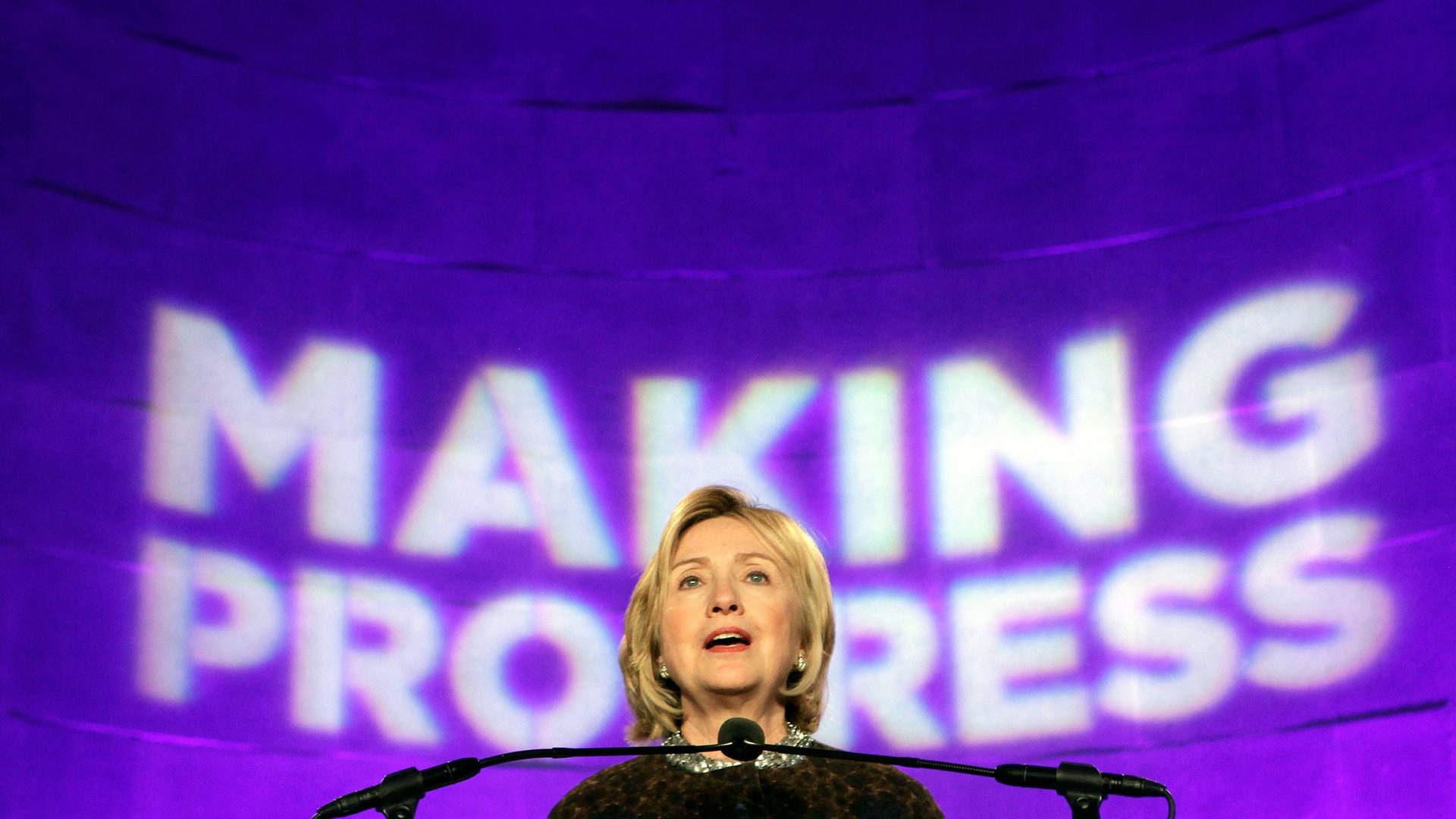

What would Hillary Clinton do to boost the US economy?

We have over eighteen months to spend hashing out Hillary Clinton’s vision for the economy. I’ll save you the time: It will look a lot like what we’ve heard from Barack Obama—and that might be a problem for her campaign.

We have over eighteen months to spend hashing out Hillary Clinton’s vision for the economy. I’ll save you the time: It will look a lot like what we’ve heard from Barack Obama—and that might be a problem for her campaign.

When the two sparred during the 2008 presidential election, there was a reason their debates hung on technical differences—should people be required to buy health insurance?—rather than broad goals like the need for universal health care in general. There’s a reason that many of Obama’s senior economic policy advisers originally worked in Bill Clinton’s administration or Hillary Clinton’s campaign. And there’s a reason so many progressive critics of the Obama administration have been begging Senator Elizabeth Warren, a reliably populist economic voice, to challenge Clinton in the primary.

Like Obama, Clinton embraces the mainstream liberal arguments about the economy: Markets work best when well-regulated; the government needs to provide a strong economic safety net for citizens; and sustainable growth means accounting for the environmental and social costs of business success, particularly when it comes to gender.

That might mean higher taxes on the rich, more government investment, policies to make workplaces friendlier to families and support for the Affordable Care Act as it exists. The highbrow version is what Larry Summers has been talking about in recent months. Vox’s Matt Yglesias notes that a recent report Summers co-authored at the Center for American Progress—widely-seen as Clinton’s shadow policy shop—outlines just this agenda.

What it won’t mean is any further campaigning to dramatically restructure the financial industry or publicly-run health insurance, as favored by the Democratic party’s left; or efforts to ditch current patent laws, attack urban rentiers, or seek root-and-branch reform of the US public education system—all ideas that attract support from more libertarian-leaning Democrats.

Indeed, you could read a 2008 Clinton speech on the economy and see rhetoric that will doubtless re-appear in the weeks ahead—”A vision for a twenty-first century economy based on shared prosperity…where we measure our success not by the wealth at the very top but by how broadly wealth is shared.”

But all the agreement between Clinton and Obama might be a problem: Obama fatigue is a real thing, and many Americans will want to know how their next president will differ from the last one, even if Obama’s policies played a major role in lifting the US from a recession. Since then, years of gridlock has left a glaring lack of progress on how to improve middle-class prosperity.

And that may be the obvious opening for Clinton—the what isn’t as important as the how: Clinton’s agenda will be as controversial among Republicans on Capital Hill as Obama’s was. When you watch her campaign, pay more attention to how she plans to enact her goals—what she stands for is already clear.