Loving eggs will always be a risky business

This post has been updated.

This post has been updated.

We should probably just get used to salmonella.

Each year, more than a million Americans are sickened with the bacteria, getting it through runny yolks at brunch, fluffy homemade mayonnaises, or countless other delicious iterations of raw eggs. They may also get it through their chicken, beef, sprouts, nuts, and many other foods. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that there were 15.19 cases per 100,000 people in 2013—and that for every reported case there are 29 that remain undiagnosed. Symptoms can include diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever and vomiting, and in extreme cases death—though some people who ingest the bacteria will not experience any symptoms at all. There are more than 2,000 strains of salmonella, a growing number of which are antibiotic-resistant.

Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that there are tens of millions of human cases of salmonella infection each year, resulting in more than 100,000 deaths.

Rates of infection in the U.S. are essentially unchanged since 2006, according to the CDC. And despite a federal jail sentence April 13 for two egg industry executives, Austin “Jack” DeCoster and his son Peter DeCoster of Quality Egg, for their role in a large 2010 salmonella outbreak, the situation isn’t likely to get any better.

Bill Marler, dubbed “the most powerful food safety attorney” by The New Yorker, attributes the outbreaks to two main factors. One: It is “unclear as to who is responsible for oversight.” And two: The bacteria is simply endemic to poultry.

Marler’s firm represents more than a hundred people sickened in the Quality Egg outbreak, which the CDC says caused 1,939 known illnesses, but could have actually hit as many as 56,000 people. The company’s ”litany of shameful conduct,” as US District Judge Mark Bennett called it, included knowingly shipping eggs with falsified processing and expiration dates and at least two instances of bribing a USDA inspector. In addition to the three-month sentences for the DeCosters, each paid $100,000 in fines and the company paid $6.8 million as part of a plea agreement.

The lack of clarity around regulation is in part to blame, Marler says, a problem highlighted in The New Yorker profile:

In the U.S., responsibility for food safety is divided among fifteen federal agencies. The most important, in addition to the F.S.I.S., is the Food and Drug Administration, in the Department of Health and Human Services. In theory, the line between these two should be simple: the F.S.I.S. inspects meat and poultry; the F.D.A. covers everything else. In practice, that line is hopelessly blurred. Fish are the province of the F.D.A.—except catfish, which falls under the F.S.I.S. Frozen cheese pizza is regulated by the F.D.A., but frozen pizza with slices of pepperoni is monitored by the F.S.I.S. Bagel dogs are F.D.A.; corn dogs, F.S.I.S. The skin of a link sausage is F.D.A., but the meat inside is F.S.I.S.

Eggs, Marler says, are like the pepperoni pizza—they fall in a gray area between multiple agencies. Plus, when it comes to chickens, salmonella is just very common, and not confined to factory farms. Marler says even his own backyard chickens might have it.

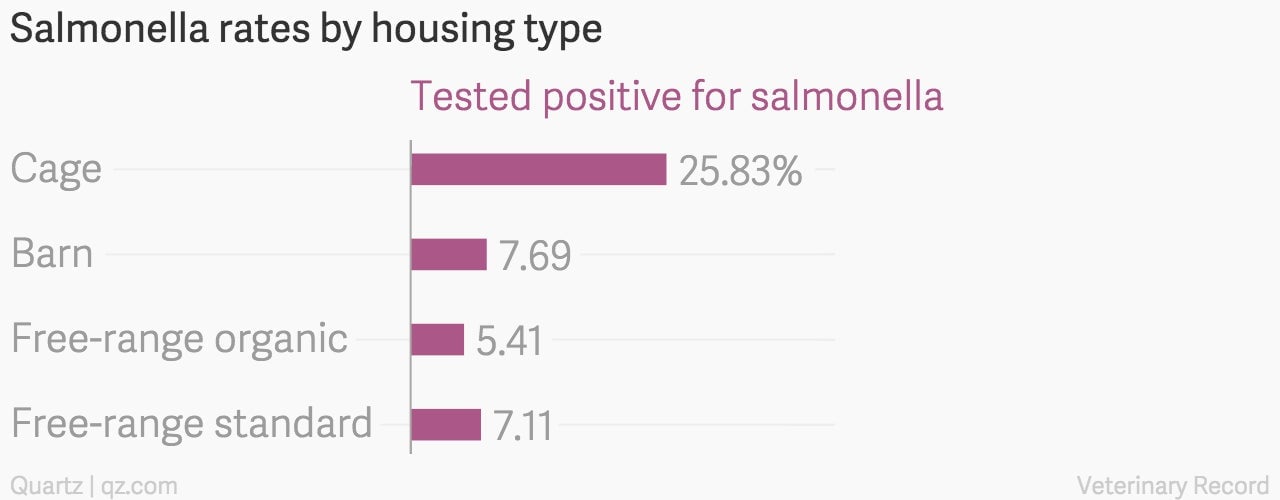

A British study published in 2010 surveyed 380 farms, looking at a variety of factors conducive to the spread of salmonella, including housing type, the number of birds in a barn, whether the farm was independent or owned by a company, and the presence of rats. It found that while rates varied depending on farming practices (caged birds were more likely to carry the bacteria, for example), there was no one silver bullet to get rid of it.

Marler is reluctant to attribute the disease to any one particular factor, noting that different studies have had different findings. Effectively dealing with the problem, he says, requires a “broad, holistic approach,” including vaccinations, good sanitation on farms, and an examination of nearly every facet of how the birds are handled.

But these kinds of changes would likely make both chicken and eggs more expensive to produce. The question, he said, is “how much more will a chicken cost?”

Update: A representative of the National Association of Egg Farmers points out that there are specific FDA regulations to reduce the risk of salmonella.