Blacklane wants to be Uber with a heart, if drivers and customers will let it

BERLIN–Providing as many cabs to as many rain-soaked drunks as possible is the challenge at the heart of the taxi app wars. The much-maligned surge-pricing model favored by Uber and Lyft is designed to get more drivers on the roads when they are needed– or at least push thrifty or less-affluent passengers to other forms of transit.

BERLIN–Providing as many cabs to as many rain-soaked drunks as possible is the challenge at the heart of the taxi app wars. The much-maligned surge-pricing model favored by Uber and Lyft is designed to get more drivers on the roads when they are needed– or at least push thrifty or less-affluent passengers to other forms of transit.

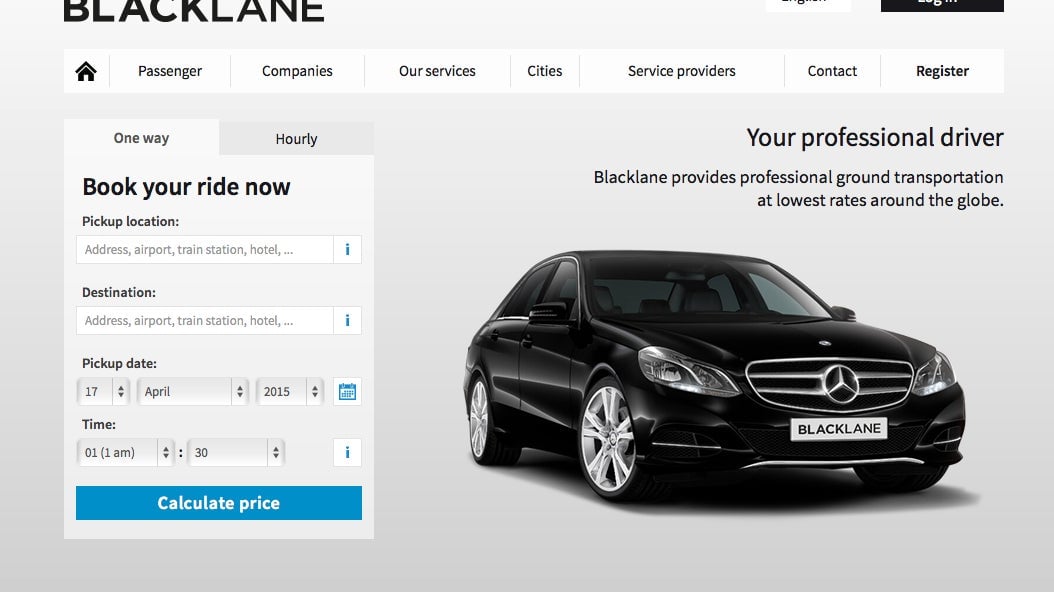

Blacklane, a Berlin-based taxi app operating in 186 cities across 50 countries, is betting on an alternative to price rationing: reverse Dutch auctions.

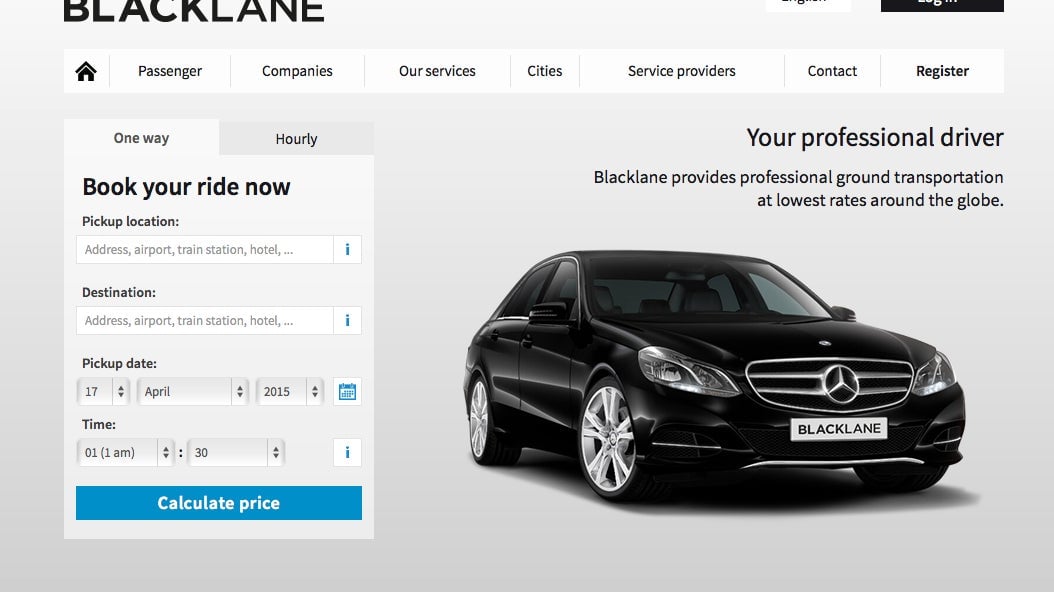

Here’s how it works: when you book a ride from Fort Greene to Newark International Airport with Blacklane, the fare is always $90.90, no matter if it’s a sunny Tuesday afternoon or rainy Thanksgiving Eve. After you book, Blacklane sends out an offer to its drivers to buy that ride for $30. (The company refuses to release hard numbers, calling its algorithm its “secret sauce.”) If no one wants the ride at $30 after a few minutes, the price bumps up to $35 and so on, until a driver buys the fare.

When demand outstrips supply – like during a snowstorm or a heavy travel weekend – and the sale price exceeds the fare, Blacklane takes the hit. Unlike Uber, Blacklane transfers the burden of market volatility from passengers to itself. Or, put another way, Uber profits when passengers are clamoring for more rides than drivers can provide. Blacklane profits when drivers are scrambling over each other for fares. A Blacklane spokesman says it’s “very rare” that the company loses money on ride auctions.

The system works because, unlike gig economy start-ups, Blacklane isn’t “creating part-time jobs that are the equivalent of Walmart greeters on wheels,” as Jon Liss recently charged of Uber. Blacklane works with established, professional livery companies and aims to soak up their excess capacity by letting drivers sell their free time. If a driver is headed to JFK anyway to pick up a client, the company lets him pick up a few extra bucks on the way.

Blacklane, which was founded in 2011, appears to be the only taxi app employing reverse Dutch auctions, but the commercial airline industry has used them for years: when a flight is overbooked, gate attendants offer increasingly sweet inducements to passengers to give up their seats. Some gig economy start-ups have used auctions too, most notably TaskRabbit, which previously allowed Taskers to bid against each other for odd jobs.

Of course, auctions are tempting to rig. Just as some Uber and Lyft drivers can game the system by creating artificial shortages, so too have Blacklane drivers sometimes colluded – labor advocates might say “organized” – to pump up auction prices.

After rolling out Blacklane in Milan, co-founders Jens Wohltorf and Frank Steuer were startled to see every ride was selling for the maximum price, at great loss to the company. They called one driver and asked what was going on. His reply? “Uh, no idea.”

“There was a kind of cartel,” Wohltorf said. “A mafia.”

This happens in about 10% of the cities in which Blacklane starts operating, usually in markets with small limousine markets. Are there other common denominators that can predict collusion? Wohltorf smiled and spoke with obvious care.

“It happens where people are used to going to the market, to the bazaar,” Wohltorf said. “Where they are used to bargaining.” (Translation: Southern Europe and developing countries.)

To combat this in Milan and elsewhere, Blacklane simply adds more and more drivers–again, labor advocates might say “scabs”–until collusion is near impossible.

Part of what makes the auction system viable is timing: rides must be ordered an hour in advance. In new markets, 70% to 80% of Blacklane’s passengers are heading to or from an airport. Corporate clients form the core of its business.

Whether reverse Dutch auctions could work for an on-demand taxi app is unclear. But arguments against the surge-pricing regime continue to proliferate. Economist Steve Randy Waldman argues that Uber’s higher-prices-equals-more-cars theory is flawed.

“If supply were in fact elastic, small increases in price would lead to large increases in supply,” he writes, rather than price hike multiples of two, three or more, as is the case now.

Another knock on surge pricing, aside from drunks being hosed, is that it only increases supply for the affluent. Matt Bruenig outlines the following hypothetical scenario:

Rich and poor jostling for cabs in the rain is messy and inefficient–and democracy at its finest. Uber represents something else.

Blacklane rides, by contrast, are always the same price and include tip, tolls and an hour of waiting time. The company is also competitive with on-demand taxi apps. My ride from Fort Greene to Newark International with UberT was $87.55. The trip home with Blacklane (in a Lincoln Towncar) was $90.90.

Blacklane is chugging along–the company was recently named Germany’s fastest growing tech start-up, and this morning, it announced it was expanding to 36 new cities in the US and Canada. (Hello, Spokane!) The company may yet find itself changing lanes, so to speak — TaskRabbit, as it turns out, eventually had to abandon the auction model amid complaints from Taskers. The company adopted a fixed-fee model last year. And while passengers on overbooked airlines have no qualms with reverse Dutch auctions, a business traveler killing two hours at an airport bar drinking Sam Adams is not an underemployed urbanite scrambling to pay rent.

How we pay people to launder our feline diarrhea-stained sheets is the $64,000 question for America’s 21st century gig economy. For better or worse, Blacklane seems to have found one more answer.