The US should encourage Japan to join the AIIB

On Apr. 15, China’s finance ministry revealed the 57 “prospective founding members” of the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), of which China is the architect. The likely founders include many US allies, such as the UK, Australia, and South Korea, which the Obama administration had lobbied not to join, seeing the AIIB as a Chinese alternative to the US-architected World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

On Apr. 15, China’s finance ministry revealed the 57 “prospective founding members” of the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), of which China is the architect. The likely founders include many US allies, such as the UK, Australia, and South Korea, which the Obama administration had lobbied not to join, seeing the AIIB as a Chinese alternative to the US-architected World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The ally snub to Washington is a diplomatic failure for the administration, although one that partially reflects the misguided refusal of the GOP-dominated Congress to ratify long-overdue IMF governance reform. This refusal made it that much easier for China to argue that new institutions to give fair voice to rising powers were both necessary and inevitable.

One major US ally that has not yet made a decision as to whether to join is Japan. The Obama administration is presumably still opposed to its participation; but whatever the merits of that position before other G7 members decided to come on board, it should be abandoned now. It is no longer in the US’s interests.

Governance of the new AIIB has not yet been determined, although China is believed to support a 75-25% voting split between Asian and non-Asian members, with voting shares within each group allocated according to gross domestic product (GDP). China also foreswore veto power, which the US has within the IMF and World Bank, in order to persuade US allies to join.

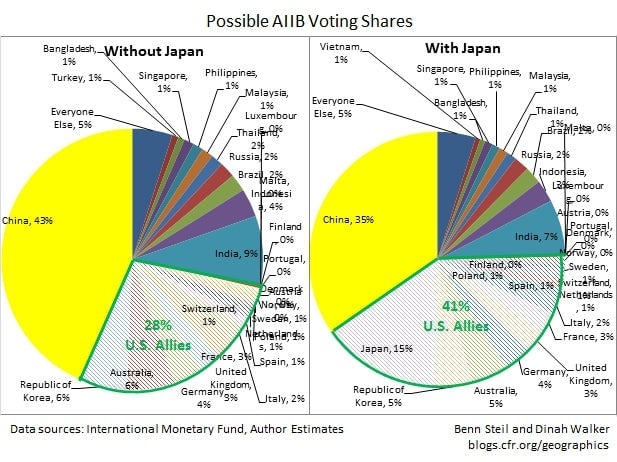

With such a governance structure, China will be highly dominant within the organization—having 43% of the votes, nearly 5 times more than number two, India (if current-dollar GDP determines voting power), as shown in the left-hand figure above. US ally countries—the UK, Germany, France, and other European nations, and Australia and South Korea in Asia-Pacific—would have only 28% of the vote.

With Japan as a member, however, close US allies would have 41% of the vote—more than China’s 35%, as shown in the right-hand figure above. Therefore, even if the United States chooses to remain outside the AIIB, it should, at this point—assuming that it wishes to temper China’s dominance—be encouraging Japan to join.