What the US can learn now from Latin America’s fight against gun violence

While we continue to wring our hands over the number of gun-related homicides and mass shootings here in the US, the experiences of our southern neighbors may offer us an idea or two. Indeed, as the chart below shows, a number of Latin American and Caribbean countries have astronomical homicide rates: Mexico’s drug war, Colombia’s decades-long battle against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), gang violence in El Salvador, the crime-ridden favelas of Brazil—there is no shortage of violence and crime in the region.

While we continue to wring our hands over the number of gun-related homicides and mass shootings here in the US, the experiences of our southern neighbors may offer us an idea or two. Indeed, as the chart below shows, a number of Latin American and Caribbean countries have astronomical homicide rates: Mexico’s drug war, Colombia’s decades-long battle against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), gang violence in El Salvador, the crime-ridden favelas of Brazil—there is no shortage of violence and crime in the region.

And with the exception of Canada, the use of firearms plays a large role in deaths across the Americas:

Granted, some of the factors that have caused rates of violence to shoot up in Latin America aren’t present in the US. Our justice system tends to work, police forces and military have more resources and training, and guerilla groups and drug traffickers aren’t operating throughout the country. But some of the factors are similar, such as inequality, access to firearms, and decisions of some (such as gang members and frustrated citizens) to take justice into their own hands.

Some of the policies undertaken to reduce violence in Latin American countries have yielded results over time. With expansions in public infrastructure, such as parks and libraries, Colombia’s notorious city of Medellin has bounced back from decades of high violence rates. In small towns in Peru, local communities have banded together to reinforce local policing efforts. Others, such as the mano dura (or heavy handed) approach that made it easier to incarcerate suspected gang members, made things worse by incarcerating youths who committed minor criminal acts (such as stealing a bicycle) and exposing them to more hardened criminals in jail. But across the region, the trend is markedly running against expansion of gun ownership and usage.

The effort to push back against the spread of guns (illegal or legal) is perhaps most evident in Mexico, where gun control is restrictive but criminals are able to easily access arms smuggled in from the US. According to former President Felipe Calderon, who oversaw the government’s efforts to crack down on drug cartel-related violence, Mexican authorities seized over 140,000 weapons (including 84,000 high-powered assault weapons) during his term. Up to 70% of these firearms were traced back to the US. In a press conference earlier this year, Calderon lamented that “One of the main factors that allows criminals to strengthen themselves is the unlimited access to high-powered weapons, which are sold freely, and also indiscriminately, in the United States of America.”

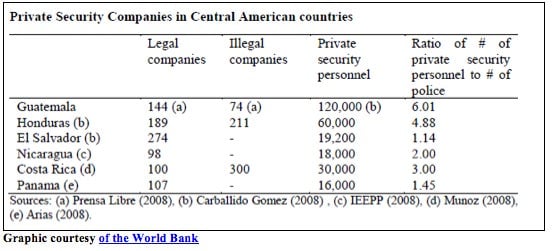

Of those countries that have seen an expansion in the use of private security forces, the results don’t look great. Guatemala and Honduras have some of the highest numbers of private security personnel, which outnumber police officers by 6 to 1 and nearly 5 to 1, respectively:

These two countries also have some of the highest rates of violence, driven largely by an expansion of organized crime and narco-traffickers seeking access to drug routes (and pushed south due to the Mexican government’s efforts to root them out). But expanded gun ownership—and a sense that individuals must erect walls, buy heavily armored cars, and take matters into their own hands—hasn’t improved security in Guatemala or Honduras. The privatization of security has instead weakened the government’s own control over the use of force.

Even if gun restrictions are generally tight, or if urban centers are heavily guarded, policymakers in Latin America are finding that they must do much more to reduce violence. The governments of two of the region’s most violent countries—El Salvador and Colombia—are seeking to demobilize gang members and guerrilla groups in order to bring peace. In El Salvador there is an agreement being hammered out among the most dangerous gangs that will create “peace zones” where gang members are promising to turn in their weapons. As Insight Crime reported earlier this month:

The leaders of the Mara Salvatrucha, Barrio 18, and three other street gangs in El Salvador said they accepted a proposal to end all gang activity in designated “zones of peace” in the country…Within these designated zones, gangs would agree to a non-aggression pact, and would commit to stopping all homicides, extortion, theft, and kidnapping… In their statement, gang leaders said that they’d already ordered affiliate groups — or “cliques” — to begin disarming in these areas, and hand over the weapons to the truce facilitators.

El Salvador has battled with gang crime for years, but the consensus among policy experts and government officials is that what is needed to tackle violence is not more guns (which are heavily regulated in El Salvador), but social policies that offer youths more education and economic opportunity. Ongoing discussions and communication among the government, the church, and gang leaders are also helping to keep a truce intact. Such policies probably wouldn’t do much to prevent the types of events seen in Newtown last week—but they could provide food for thought as US cities from Los Angeles to Chicago continue to seek to reduce violence among gangs there.

In war-torn Colombia, the Juan Manuel Santos administration is pushing ahead with peace talks with the FARC to end over 50 years of armed conflict. Despite the country’s restrictive gun ownership laws, gun usage in Colombia is widespread among illegal armed groups—there are an estimated 800,000 to 2.4 million illicit guns held in the country. Following decades of kidnapping, bombing, and assassination attempts, security is tight. Armed guards equipped with rifles, bomb-sniffing dogs and body armor pace in front of virtually every business, government office, and some high-end hotels in Bogota. Bomb-sniffing dogs are led around tourist areas, airports, hotels and business centers.

But Santos—who also held the post of defense minister during the last administration—isn’t advocating for more security, or more guns. Instead, he’s trying to negotiate a peace agreement that will urge the nearly 8,000 FARC combatants to demobilize and reintegrate into mainstream society. As talks have progressed, other illegal armed groups (such as the National Liberation Army) are eyeing the negotiations as having real potential for ending Colombia’s armed conflict. Colombia will need more than just the surrender of guns to resolve its struggles with violence and conflict, but demobilization efforts are clearly a step forward.

There are many factors that provoke violence in Latin America and in the US—and not all the same policy ideas will be relevant or useful. Across the region, a common gut reaction has been to seek quick and draconian measures. Many will insist that individual efforts (such as arming ourselves and making more ubiquitous the “good guy with a gun“) are necessary to better protect ourselves. But some of the success stories—from San Salvador to Medellin—point not to more security, and not to more guns, but to investments in society and in communication.