Who cares that Clinton eats Chipotle and Jeb is paleo, anyway? Everyone, apparently.

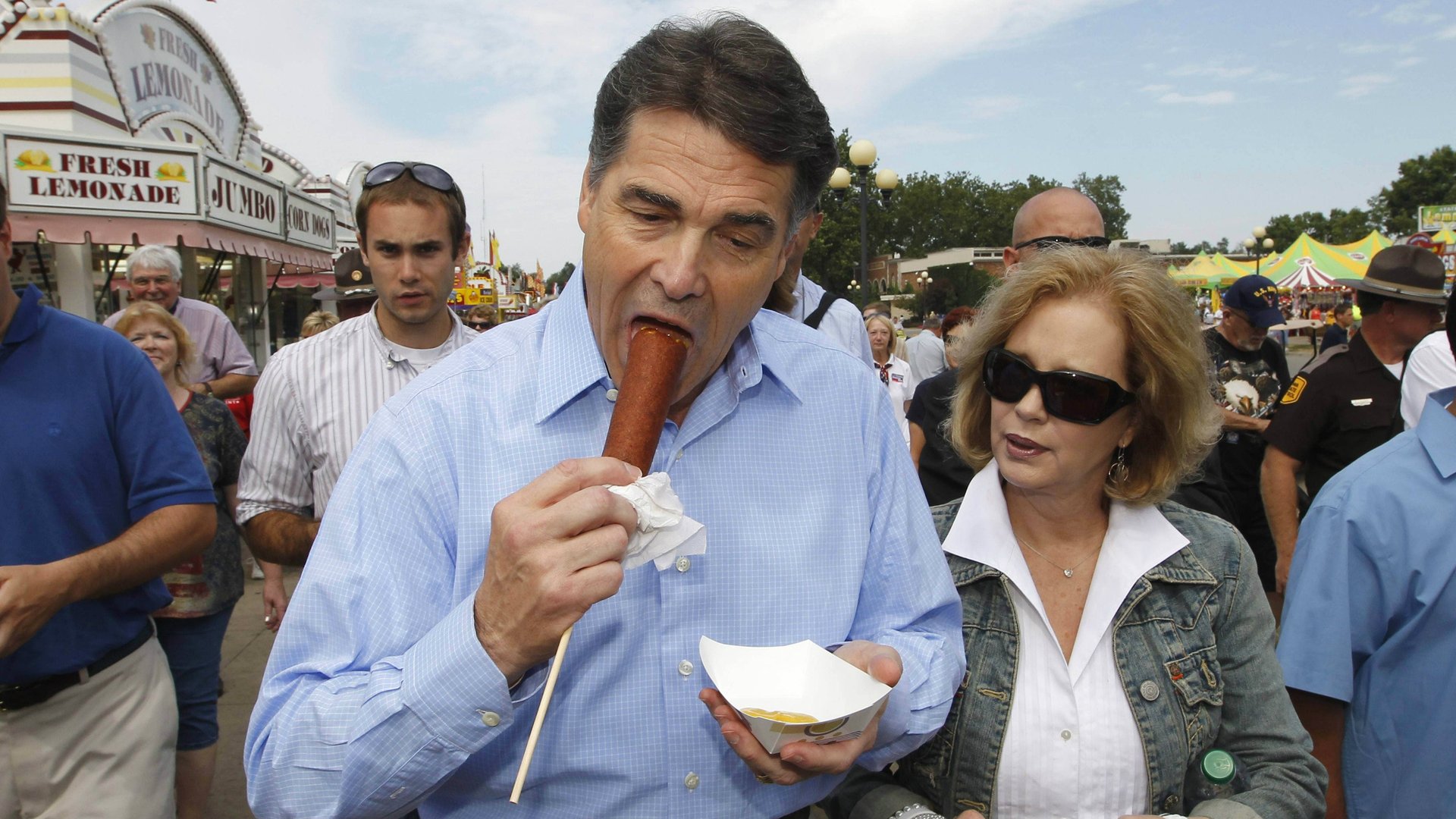

It is every American politician’s God-given right to overeat on the campaign trail. Corn dogs, barbecue, Chipotle—it’s all in a day’s work if you’re looking to become the next president of the United States.

It is every American politician’s God-given right to overeat on the campaign trail. Corn dogs, barbecue, Chipotle—it’s all in a day’s work if you’re looking to become the next president of the United States.

But despite its long tradition in American politics, eating for the cameras doesn’t win elections. Even if it helps a candidate connect with the locals, it’s unlikely to change the way people vote. In fact, it’s just as likely to turn into an embarrassment.

Using food to woo voters has a long history, says Fred Opie, a food historian at Babson College in Massachusetts. President Andrew Jackson’s 1829 inauguration barbecue at the White House—called “the wildest party in White House history” by the National Constitution Center—is well known, but even that wasn’t his first foray into using a grill to appeal to the masses. He started the tradition in the summer of 1822 at a barbecue in Nashville, while preparing for his first presidential bid in 1824, writes Andrew Warnes in Savage Barbecue: Race, Culture, and the Invention of America’s First Food. “From this point forward, the General’s campaigners used barbecue to stoke what his contemporaries would call ‘Jackson Fever,’ promoting the grassroots credentials of their man by associating him with the most grassroots of American foods.”

Jackson didn’t win in 1824. But the next time around, he used barbecues as part of a larger, organized effort to win widespread support for his nascent Democratic party. The plan worked: Jackson won by wide margins. And when it was time to celebrate, he invited his supporters to the White House on Inauguration Day. Between 10,000 and 20,000 obliged.

Fast forward to the 20th and 21st century, and eating while campaigning has become a basic expectation for candidates. But it has also become a distraction at best and a liability at worst. Hillary Clinton’s recent unannounced stop at a Chipotle fast-food joint garnered her exponentially more attention than all of the official coffee shop meet-and-greets she’s done. “It wasn’t intended to be a public event,” says Michael G. Miller, a political scientist at Barnard College. ”This was just, we’re driving to an event and got hungry,” he says. (Quartz reached out to the Clinton campaign for comment; we’ll update if we get one.)

All of the speculation about the true meaning of Clinton’s dining choice (she’s so liberal! It was “Hispanic outreach!” Or it was another sign of McDonald’s demise!) outshone all of the meticulously planned, non-corporate, non-franchised-location events, where her message—”I’m just like you,” says Opie—was loud and clear.

Still, it hardly compares to the shellacking other candidates have taken for their food faux pas. Even before then-candidate Barack Obama asked Iowa farmers if they’d seen the price of Whole Foods’ arugula lately (they had not—the state didn’t have a Whole Foods), George McGovern ordered a kosher hot dog with milk (a completely unkosher combination), and George H.W. Bush marveled over a grocery-store scanner. (As a 1992 New York Times headline recounted, “Bush Encounters the Supermarket, Amazed.”) The takeaway from each of these incidents: The candidates are out of touch with the exact voters they’re trying to connect to.

“Gaffes usually hurt when they’re consistent with the things opponents want you to think of a candidate,” says Miller. Things like: Obama is an intellectual snob. McGovern was a country boy unaccustomed to city life. Bush was crazy rich.

Few politicians know the pitfalls of a food gaffe like the Republican presidential challenger in 2012, Mitt Romney. He told a Mississippi crowd he was an “unofficial Southerner” because, “I’m learning to say ‘y’all and I like grits.” That kind of statement, says Opie, was akin to saying, “‘You all are exotic,’ [when] instead, the message should be, ‘I’m just like you.'” The next month, at a Pittsburgh area picnic, Romney insulted the cookies: “I’m not sure about these cookies. They don’t look like you made them. No, no. They came from the 7-11 bakery, or whatever.” They were from a famous local bakery.

But in a presidential election, Miller says, these kinds of incidents don’t change the way voters think; rather, they reinforce preexisting dispositions. “Ninety percent of this country is partisan,” he says. “How we form preferences is based mainly on our partisanship.” Voters already thought Romney was out of touch, and those incidents just reinforced it. “Elections are actually won by mobilization,” he says.

For all the lessons to be learned about the dangers of eating while politicking, it’s unlikely to change. Some stops are all but required for candidates, like the Hamburg Inn in Iowa City, where, according to kitchen manager Tyler Devine, essentially every politician since Ronald Reagan has ordered his meatloaf and apple pie. Or the Iowa State Fair, where downing a corn dog is a must.

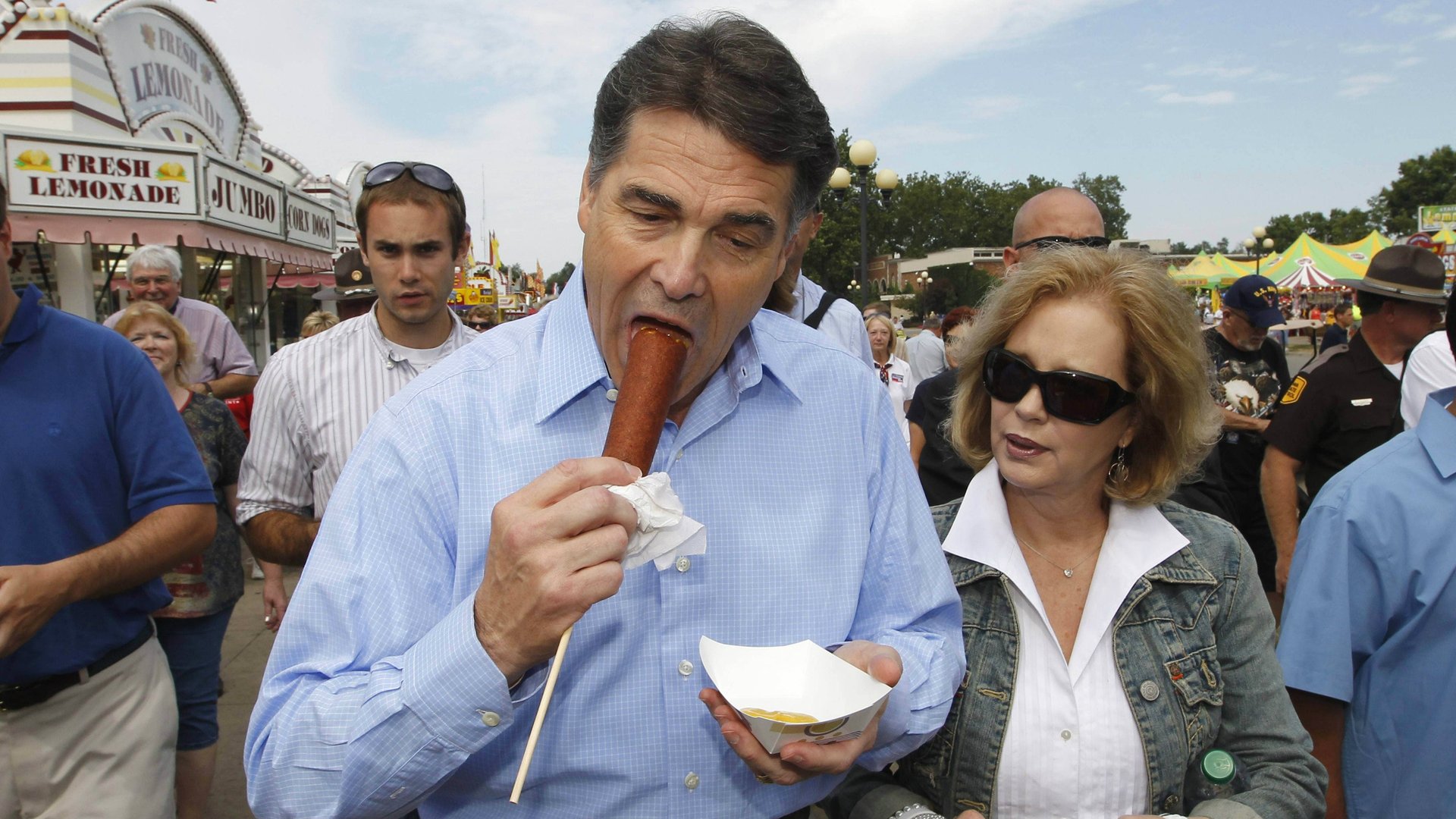

Even as Americans move to healthier foods, candidates, at least in public on the campaign trail, are unlikely to follow. Voters, says Opie, want candidates who eat a lot. Think Bill Clinton endearing himself to Americans with French fries and Big Macs (memorialized in this classic Phil Hartman Saturday Night Live skit). Picky eaters make people uncomfortable.

Candidates like Florida governor Jeb Bush, who is, according to the New York Times, really trying to keep his paleo diet, can stick to the tried-and-true practice of takeout—grabbing a doggie bag at the diner or pie house they’re visiting, and then handing it off to a staffer as soon as they’re back on the bus. But skipping meals probably isn’t a good plan, either—something Jeb apparently realizes, since as the Times notes, he cheats.

“Politicians that are the best are the ones who eat anything and drink anything,” says Opie. “George W. Bush had a drinking problem for a long time. He did not drink. But he would always have a can in his hand, whether it was a soda or something else.”