Five economic charts that will define 2013

The end of the year is accompanied by a flurry of predictions from financial analysts about what the new year will bring. 2012 has been a year of political gridlock in Europe, topped off by the end-of-year fiscal cliff debates in the US and the election of monetary policy activist Shinzo Abe in Japan.

The end of the year is accompanied by a flurry of predictions from financial analysts about what the new year will bring. 2012 has been a year of political gridlock in Europe, topped off by the end-of-year fiscal cliff debates in the US and the election of monetary policy activist Shinzo Abe in Japan.

What will define 2013? We’ve pored over reports and found some of the most intriguing charts and insights that we’re watching next year.

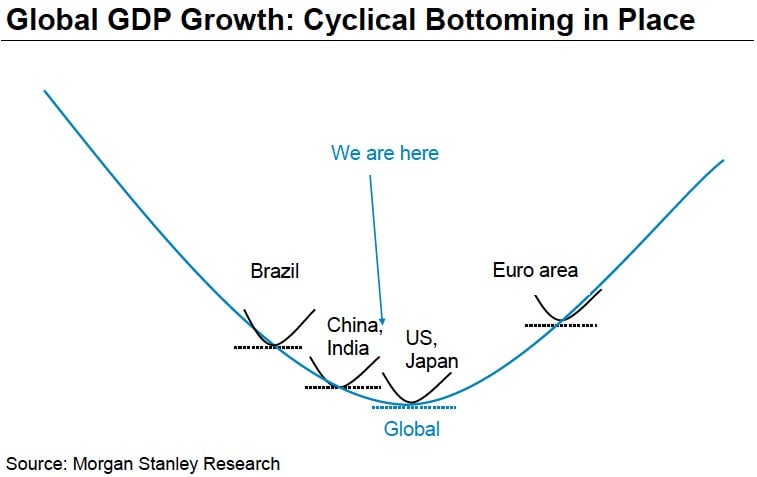

1. An uneven global recovery

More than five years since the global financial crisis began, countries have yet to iron out the problems caused by housing bubbles, bank failures, and politics. Recent economic data suggest that the worst may be over in some countries, but others still face obstacles ahead.

By Morgan Stanley’s approximation, emerging-market giants Brazil, China, and India have already bottomed out. However, their exports and manufacturing depend upon demand from advanced economies like Japan, the US, and Europe. This could be the key impediment for stronger growth next year, Morgan Stanley economists explain:

The global economy looks set to remain stuck in the Twilight Zone that divides sustainable expansion from renewed recession in the foreseeable future. We now forecast global GDP to grow by barely more than 3% in 2013, the same as this year and exactly halfway between the 2.5% recession threshold and the 3.7% long-term trend… EM economies face external and internal challenges that render the old, export-led model of growth defunct. Weak [developed market] consumers, onshoring of DM manufacturing and risks to external funding all work against EMs externally.

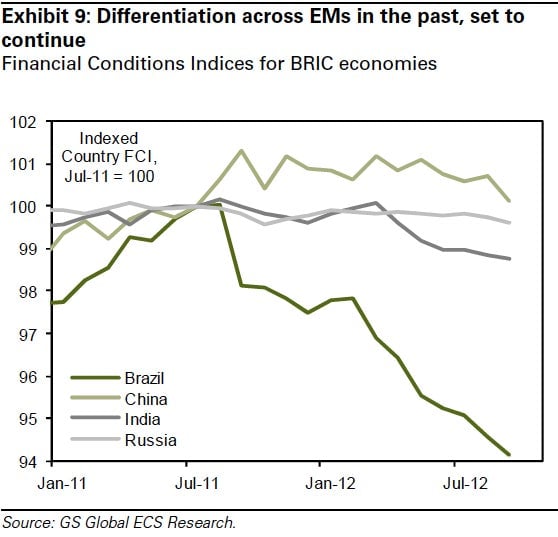

2. Emerging-market winners and losers

Aside from the gap between emerging and developed markets, economists are concerned about differences among emerging markets, and especially about a laggard Brazil. Many expect these divisions to widen. “While we expect the EM universe as a whole to see better growth and somewhat more inflationary pressure, the differences across EM are at least as striking as their similarities,” write a team of Goldman Sachs economists.

“What makes this year different is our global team’s view that the outlook for 2013 could change depending on the actions taken by policy-makers,” writes Morgan Stanley analyst Gray Newman. While politicians may succeed in driving investment to the right places or undertaking the right monetary policy measures, those decisions aren’t always made for the long-term.

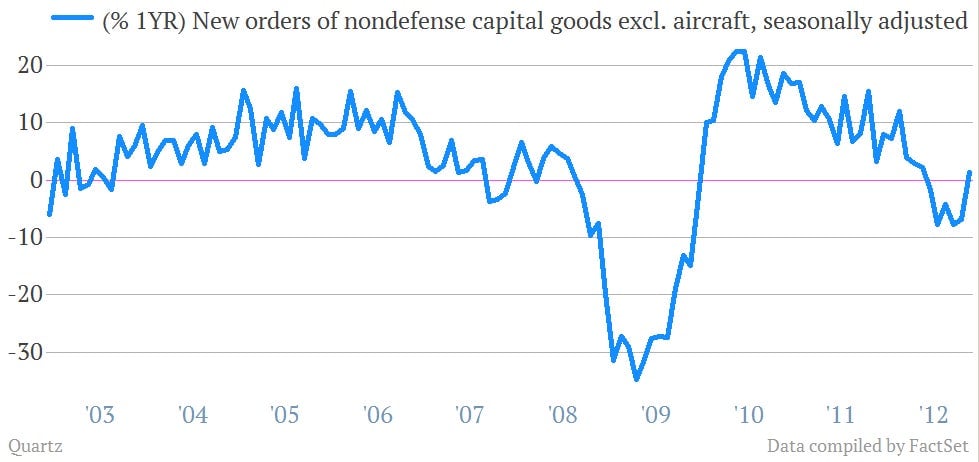

3. The legacy of the fiscal cliff dive

Debates and negotiations over how to resolve the so-called fiscal cliff—a combination of spending cuts and tax increases, topped with another debate about raising the public debt ceiling—have plagued American politicians for months. With just a few days left, Republicans and Democrats remain dangerously far apart.

But even if you expect an eleventh-hour pact, it’s unclear whether non-financial companies will feel the burden of the end-of-the-year debate. The way we’ll look for that is in capital expenditures (capex)—a measure of how much companies are spending on new investments, which would set the US economy up for growth. Lombard Street Research’s Charles Dumas lays out the stakes:

Quick recovery is unlikely, and declining capex means that the fall in profits corresponding to a given fall in the financial balance is that much larger. Q4 GDP growth could be under 1% annualised. A 10% fall in business capex, with probably some negative effect from inventories, will mean more than a 1% negative contribution to GDP growth from business spending.

Business capex dropped sharply in October and recovered in November, so it’s unclear if the fiscal cliff has had any effect on how companies behave. This means politicians and economists who predicted that companies would hike investment and hiring once the cliff is resolved could be proved wrong if it turns out that investment and hiring weren’t depressed in the first place. We should have a better answer early in 2013.

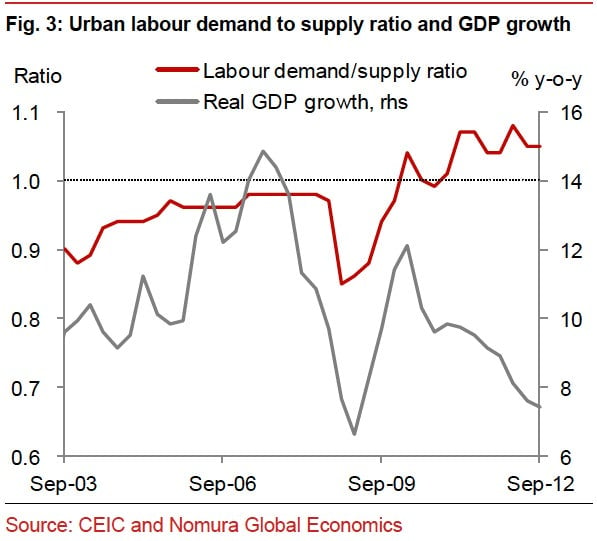

4. China’s landing sequence

Economists have been watching China’s slowing growth like hawks throughout the year. They’ve debated ad nauseam about whether this slowdown will be a “hard” landing (4%-5% growth) or a “soft” one (8%-9%), while generally agreeing that a return to levels of 10% or more is unlikely.

Nomura argues that key to understanding China’s future is the supply and demand of labor. A lot of the economy’s growth to date has been driven by vast investment in labor-intensive projects. But those days may be nearing an end, Nomura says:

We believe China’s potential growth has now slowed to 7.0-7.5%. The key driver of this slowdown is the depletion of excess labor. China used to have a huge pool of excess labor in its rural inland regions, estimated at 250 million persons. Over the past ten years, this group of labor was gradually absorbed into the industrial sector. The ratio of urban labor demand to supply has risen to above 1.0 since December 2010, which suggests that labor markets have turned from structurally oversupplied to fully employed and structurally tight.

Economists believe that if China can turn more of these workers into consumers and sweep away some of the red tape making it hard for foreign firms and financiers to reach those consumers, the country may be able to avoid a more severe economic slowdown. Whether this can happen in 2013 remains to be seen.

5. The duration of euro agony

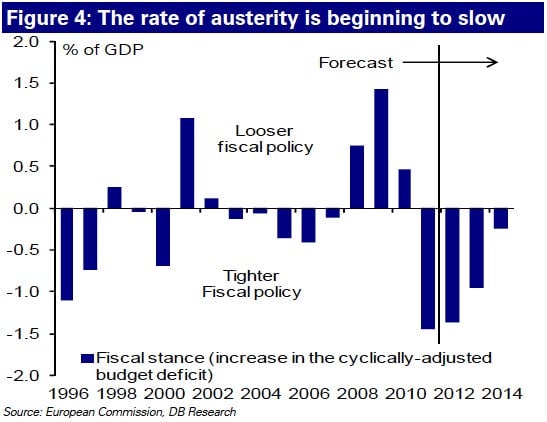

Recent decisions from European leaders have convinced markets that the euro probably won’t go bust, Greece probably won’t leave, and the region will probably suffer from a protracted—but not crippling—recession. Leaders seem to have discovered that austerity alone is not the answer to the crisis, and relaxed their strict targets for Greece and Spain. That said, this is a brand new tune, and they could still screw up the performance.