Don’t trust Chinese business partners—except when you want to

Last year, a UK-based petroleum company called Tethys lost a hard-fought bid for oil fields in northern Afghanistan to China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Tethys groused that CNPC had made an uncommercial offer. Over the subsequent months, one of Tethys’s strategic advisers, former senior US diplomat Zalmay Khalilzad, launched a bitter fusillade over the deal. It was the fault of Washington, which was engaged in commercial abdication to China around the world, wrote Khalilzad and Alexander Benard, his son and managing director of their consultancy, Gryphon Partners, in numerous essays.

Last year, a UK-based petroleum company called Tethys lost a hard-fought bid for oil fields in northern Afghanistan to China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Tethys groused that CNPC had made an uncommercial offer. Over the subsequent months, one of Tethys’s strategic advisers, former senior US diplomat Zalmay Khalilzad, launched a bitter fusillade over the deal. It was the fault of Washington, which was engaged in commercial abdication to China around the world, wrote Khalilzad and Alexander Benard, his son and managing director of their consultancy, Gryphon Partners, in numerous essays.

Chinese companies, backed by their government, they argued, were over-promising, bribing and generally being bad business partners for the wrong-headed nations that awarded them contracts. “Chinese businesses are among the most corrupt in the world; a recent report from Transparency International ranked them more likely to pay a bribe than anyone but their Russian counterparts,” Benard wrote in one article. He argued that “China’s corporations also sometimes try to renegotiate the original terms of agreements once they have established a presence on the ground.” On the ground, he said, Chinese companies are prone to use subcontractors that “lack relevant experience, since Chinese officials see these as a chance to dole out favors to politically connected companies that may be technically unqualified.”

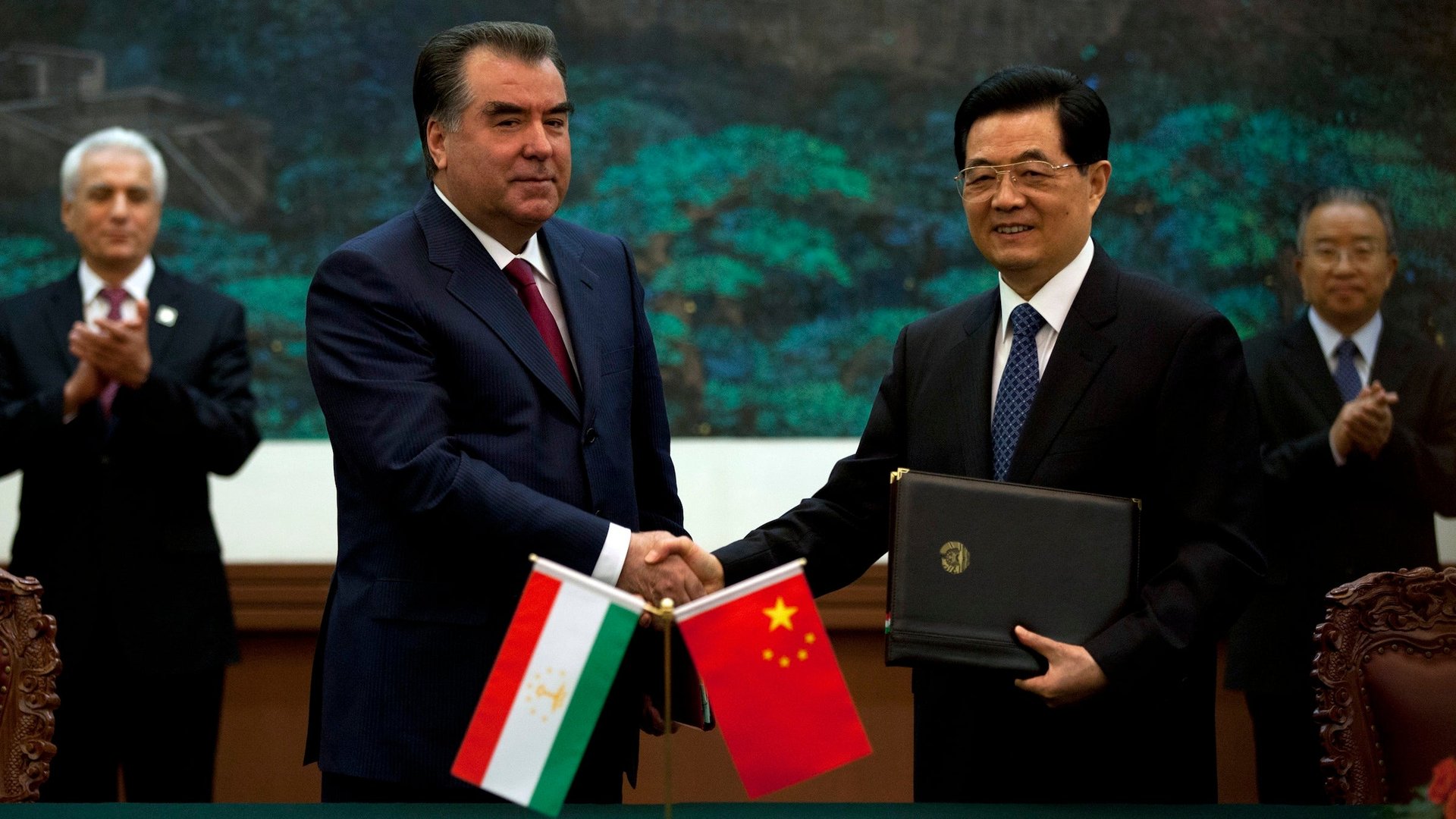

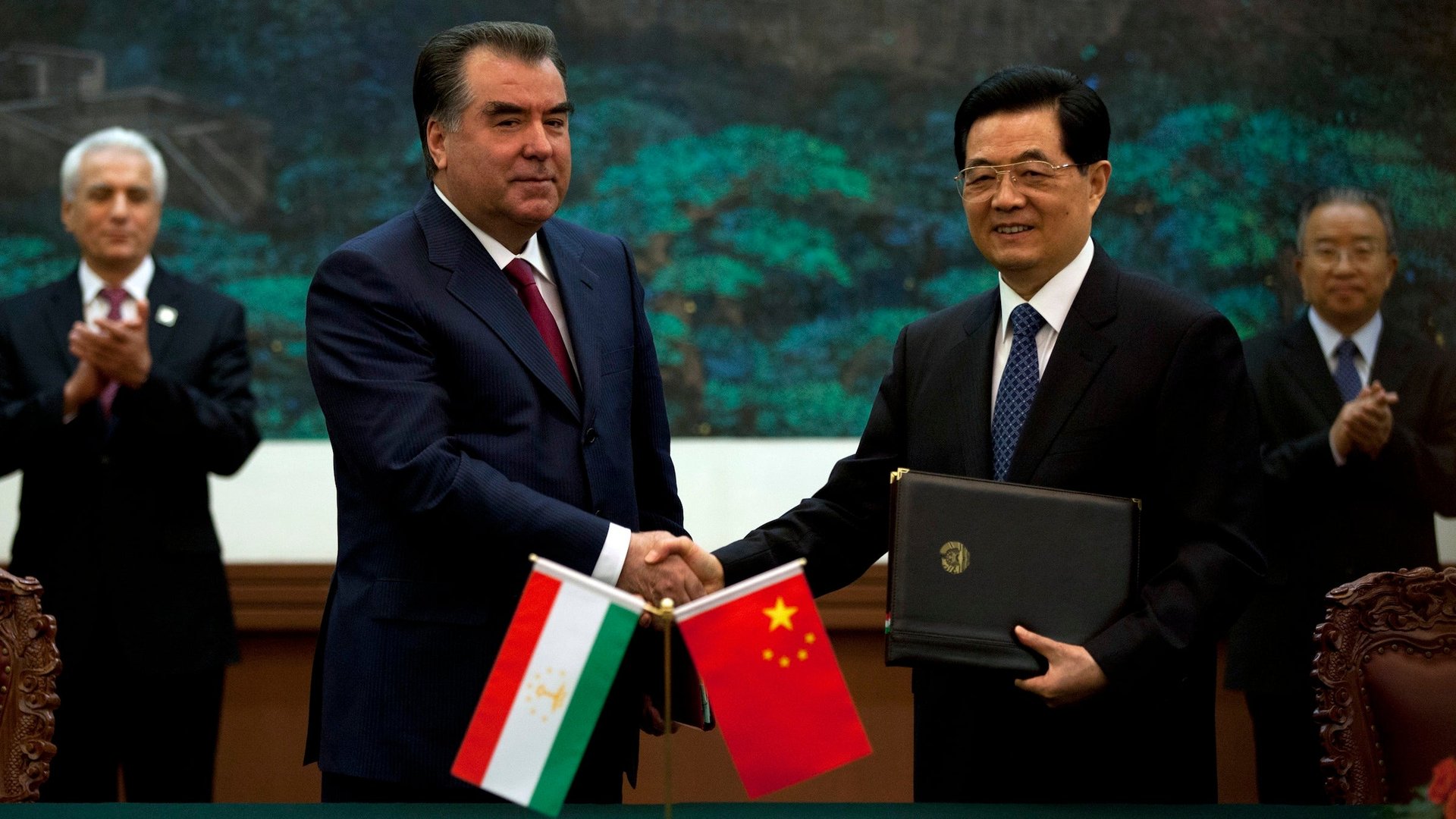

Fast forward. On Dec. 21, Tethys announced that in Tajikistan, where it was also prospecting for oil, it now has two new partners–France’s Total, and its old rival, CNPC. As part of the “farm-in” deal, the two companies will pay $60 million to Tethys, amounting to two-thirds of the costs that the company has accumulated while exploring a field called Bokhtar, in the Amu Darya basin. According to an audit, the field holds the oil and gas equivalent of 27 billion barrels of petroleum in place; that is a gigantic resource base, but at this point it is an aspirational volume—it is not known how much of the oil and gas can be recovered.

But the announcement of the French-Chinese farm-in has ignited a surge in Tethys’s share price, since the injection of expertise (Total) and cash (Total and CNPC) make the potential much more likely to be realized.

So why the sudden willingness to work with the Chinese, if they are as corrupt, cronyist, and unreliable as Benard wrote? Shouldn’t they be kept at arm’s length? I have in fact argued the opposite—that, when it comes to stability in Central Asia and Afghanistan, China’s very resource hunger makes for a rare Sino-Western alignment of strategic interests.

Tethys did not respond to an email, but I also emailed Khalilzad, with whom I have crossed swords in print over the issue of Chinese investment in Afghanistan. He responded:

I have not taken issue with China’s investments in Afghan resources. I believe that Afghanistan has the right to award concessions to CNPC or any other bidder, and that the country on balance benefits from foreign investment.

My position has been quite consistent. As I stated in my October 19 rebuttal to your post in [Foreign Policy], Gryphon Partners does not ‘have a problem with Chinese investment in Afghanistan,’ nor do we ‘believe that Afghans should be required to turn over the development of minerals to the United States as a reward for ongoing US sacrifices in Afghanistan.’

My objection was to the US government spending taxpayer money on a tendering process that favored CNPC, a Chinese state-owned company, at the expense of Western firms.

In this regard the Tajikistan and Afghan deals are fundamentally different, according to Khalilzad. “The Bokhtar agreement is between three companies: Tethys and Total—publicly traded western firms with many large US investors—and CNPC. US taxpayer money was not involved in the deal.” He added, “Although I am a member of Tethys’s board, my firm, Gryphon Partners, played no role in facilitating the agreement.”