Climate change could wipe out one in six of the world’s species

This post originally appeared at InsideClimate News.

This post originally appeared at InsideClimate News.

If countries’ greenhouse gas emissions continue unchecked, one in every six species on the planet could go extinct.

That is the finding of new research published this week in the journal Science. Climate change is a big factor in what has been tagged ”The Sixth Extinction,” potentially the worst die-off in Earth’s history since the dinosaurs disappeared 65 million years ago. Ecologists warn it could threaten our economy, food security, and human health.

“Imagine if we lose an important predator for an agricultural pest,” said Mark Urban, an expert in ecology and evolution at the University of Connecticut and author of the new study. “Suddenly we have a major pest problem that threatens our ability to grow food.”

Plants, animals, birds, and insects on land and in oceans are already struggling to adapt. Their habitats are shifting in response to warming temperatures, as rainfall patterns change, and as the other species they rely on for nourishment or protection shift as well. The American pika, a small mouse-like mammal intolerant of heat, for example, has already disappeared from more than one-third of its known mountain habitats.

Warming ocean temperatures are threatening coral across the globe. Sea level rise is eliminating the mangrove forest habitats of India’s tigers and shrinking the South American beaches used by sea turtles to lay their eggs.

The extinctions could also restrict humans’ ability to fight climate change as biologically rich carbon sinks like the Amazon rainforest begin to disappear. There’s also the critical role that biodiversity has played in culture and art across the globe for millennia.

Scientists for years have been trying to quantify the extent of climate change-driven extinction. Dozens of studies have been published, with extinction percentages ranging from zero to 54%. Urban analyzed 131 of these predictions to get an average.

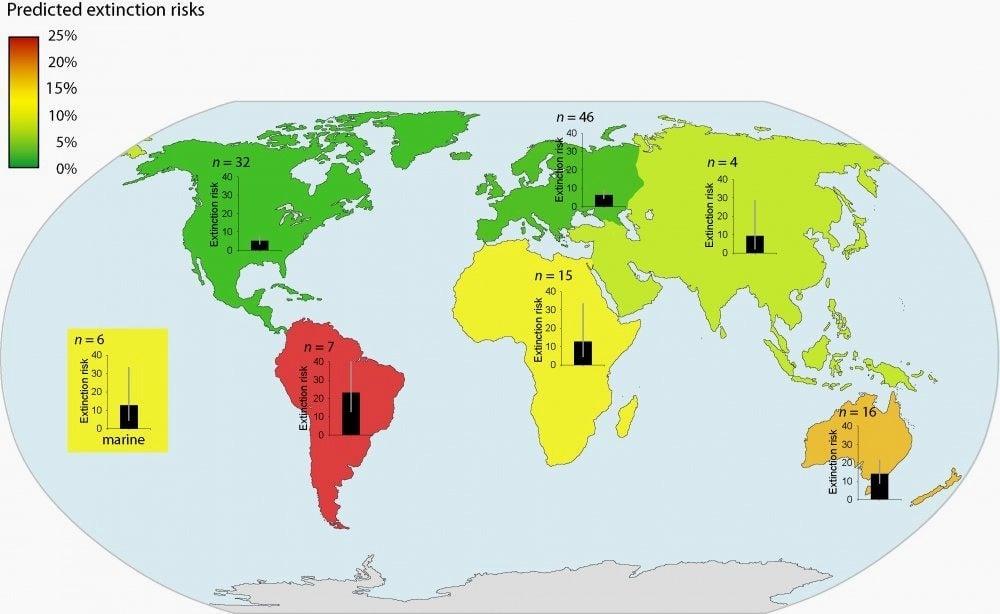

Stuart Pimm, an expert on extinctions at Duke University, said Urban’s analysis has some limitations, including scientists’ inability to predict whether species will adapt or die off, but said his broad takeaways are correct. He agreed that the less governments do to combat climate change, the higher the extinction rates will be. Some regions, such as South America, will see more extensive die-offs than others.

“There is a growing sense of the ubiquity about climate change and its impact on species and extinction,” said Pimm.

Urban found the world could lose 5.2% of its species if temperatures rise 2 °C—which world leaders agree the world must stay under to avoid catastrophe and which scientists say is now likely unavoidable. If the Earth warms 3 °C, this extinction rate jumps to 8.5%. If temperatures increase 4.3 °C, a likely scenario if nations refuse to curb their emissions soon, 16% of species will be lost.

South America faces the worst extinction possibilities, with 23% of its species likely to disappear as a result of climate change. Australia and New Zealand could see declines of 14%, while North America and Europe would lose just 5 and 6%, respectively.

“We are going to hand over to our children and grandchildren a world that is seriously depleted,” presenting ethical and aesthetic problems, Pimm said. But this loss of diversity also “matters to the poorest people on earth, who depend upon nature to survive.”

For more like this, see InsideClimateNews.org.