Educating a child in Baltimore is far better than giving them a slap on the head

I grew up in Baltimore. Specifically, East Baltimore, in a neighborhood called Ednor Gardens-Lakeside. My neighborhood was a bit better off than Freddie Gray’s–definitely working class, but bereft of boarded-up homes and businesses. My mother would tell me growing up that we were the working poor–poor, but at least we had jobs. I would call the way I grew up ghetto adjacent–we had tree-lined streets, but gang territory was just five blocks away. Some of our neighbors had nuclear families. If my mother sent me to the store to buy something, I would walk a mile to the shopping center (or a half-mile to the store in a better part of the neighborhood), rather than go to the neighborhood store a few blocks away. Sometimes my mom would make fun of that, but I think she secretly preferred it that way.

I grew up in Baltimore. Specifically, East Baltimore, in a neighborhood called Ednor Gardens-Lakeside. My neighborhood was a bit better off than Freddie Gray’s–definitely working class, but bereft of boarded-up homes and businesses. My mother would tell me growing up that we were the working poor–poor, but at least we had jobs. I would call the way I grew up ghetto adjacent–we had tree-lined streets, but gang territory was just five blocks away. Some of our neighbors had nuclear families. If my mother sent me to the store to buy something, I would walk a mile to the shopping center (or a half-mile to the store in a better part of the neighborhood), rather than go to the neighborhood store a few blocks away. Sometimes my mom would make fun of that, but I think she secretly preferred it that way.

I was born a precocious child. I started to learn to read in English at 18 months, started to learn Spanish at 2, and Hebrew at 7. Left undirected, my intelligence could have made me an established drug dealer, an inspiration for a character on The Wire. My mother must have wondered what to do with me. At age 4 ½, she gave me the best gift a mother in 1982 could have given her child.

She got me a computer.

A little Timex/Sinclair 1000, which I would eventually upgrade to a Commodore VIC 20, followed by a Commodore 64.

I initially thought that the BASIC programming language was English (hey, it had words like “load”, “save”, and “return”), and tried to pronounce keywords like LPRINT and GOSUB. I would write my first functioning “app” by age 6 or 7–creating little mazes on the screen, which I would then attempt to solve with a Crayola marker, to my mother’s dismay. When I asked her for more video games for my Commodore 64 at age 8 or so, she got me a book on Commodore 64 programming: “Make ya own games!” My greatest exploit would be getting a balloon to bounce around the screen. I would first get online at 13–and begin to meet kids (and weird adults) from around the world, expanding my horizons far beyond my East Baltimore neighborhood.

And without either of us knowing it, I would gain the most marketable job skill of all time.

When my mother first saw that I had above-average intelligence as a child, instead of trying to “mainstream” me into public schools at the time, she found a (now-defunct, thanks, GOP budget cuts) Gifted and Talented Education program for my elementary schooling. When that wasn’t enough, she found Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth, an organization whose after-school, Saturday, and summer programs I credit with making me who I am to this day.

There were years when I was in school up to 10 hours a day, and half-days on Saturday. There were times as a kid when all of my waking hours were either spent in class or doing homework. High school was year-round, thanks to Phillips Academy of Andover’s “Math and Science for Minority Students” program.

My mother couldn’t afford private schools or tutors–my mother raised me on $9.75 an hour. She got me books. She scoured the newspaper (remember, this was the 80s) for any free or discounted program she could find that would keep her bright son occupied.

And I thank her to this day for it. And I wish all young black boys had the same opportunity.

Toya Graham is being heralded as #heromom for slapping her child upside the head. Yes, she pulled him from a riot. Yes, she wanted to stop him from being another Freddie Gray (as if any amount of mom-beating could have prevented a John Crawford from being shot while buying a legal BB gun). But did Toya Graham give her son the tools to escape the situation that created the unrest in Baltimore in the first place?

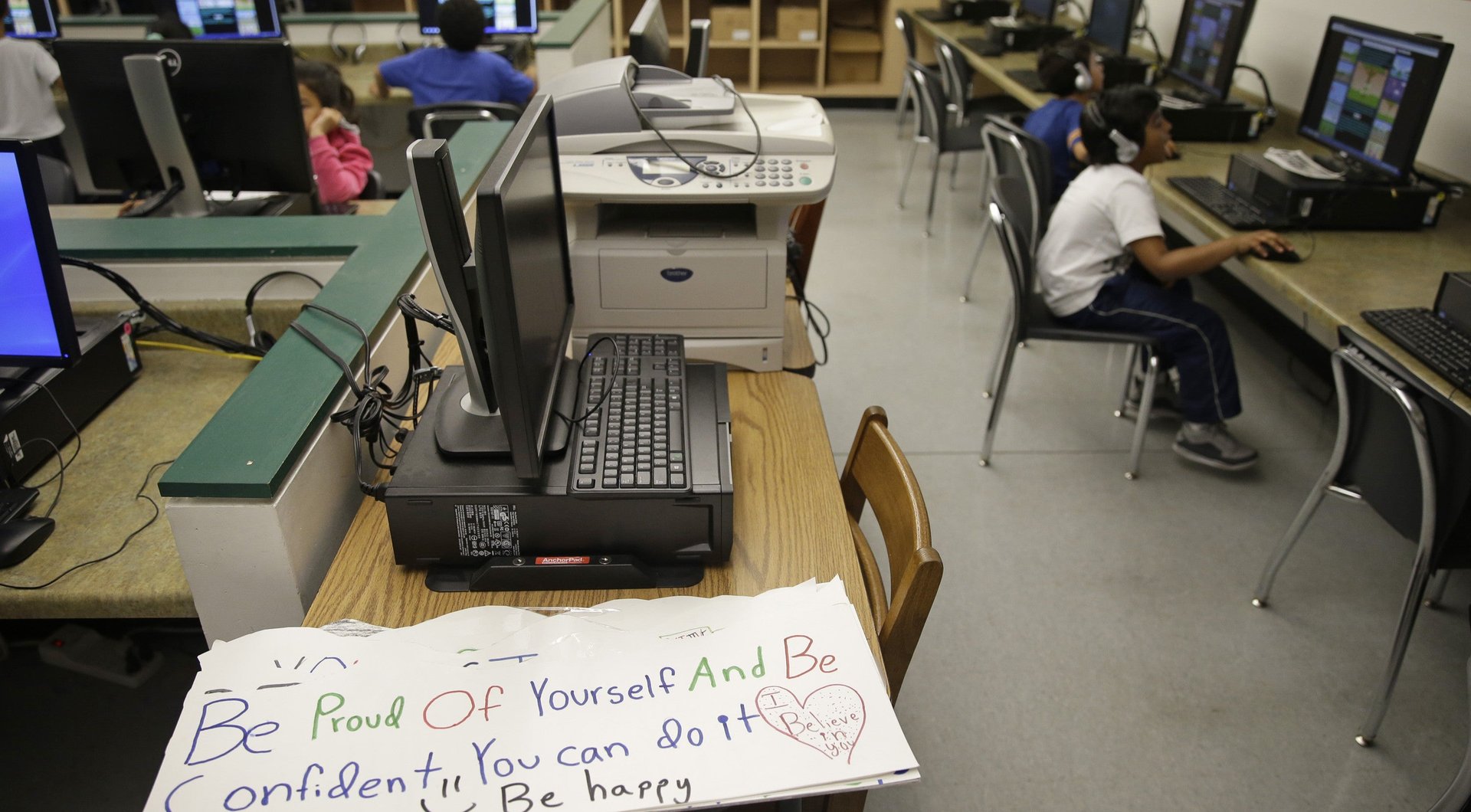

How many of those kids in the #BaltimoreUprising could be successful, if only they had the tools with which to generate success? The next Bill Gates or Marissa Mayer could be somewhere in that crowd, but who will tap their mental ability for good?

Kids who can organize this well on social media–how many #brands could use this knowledge? Kids who can get swarms of their peers to identify with them and follow their leadership–are these not the managers companies want?

These past few weeks I have been beside myself, crying with privilege guilt–here I am, senior web developer at one of the world’s leading digital media sites, hiphop artist on two continents, sipping Sancerre, while some people I grew up with can’t get “good water”. I debate GMO vs heirloom tomatoes while some of my friends have no access to fresh food (PDF), if there’s even food in the store–if there’s even a store. I lament subway inconveniences while my some of my old neighbors can’t take a bus to work, because there isn’t one running. I buy fine soaps and toiletries, while people in my hometown have to steal toilet paper to wipe themselves.

But then, I’m humbled by realizing that I’m where I am today because of generously funded private and public programs that filled my idle time with education. Because of a mother who sought them out, because of a family that supported her decisions, and because of friends who egged me on to do my best. Mothers who give their children opportunity, ways out, and skills to better themselves and their communities–these are the hero moms.

And my mother, Lucretia Diggs, was one of them.

I lost my mother in 2004 to drug addiction–Baltimore has been rife with addiction for over 35 years–and her 60th birthday would have been a few weeks ago. Her story is similar to so many others’ in urban black communities – pregnant at 21, a struggling single mom at 22. She was raising an only son, just like Toya Graham. But what she did for me would make me dissimilar from everyone else I grew up with. Of course I would be a rebellious teen like anyone else, and I got in plenty of trouble, but I was different. She made me a “bookworm”, a “whiz kid”, a dork.

It was the best gift she could have given me. I wish I could thank her, but I can definitely say one thing.

My mother did way more for me than Toya Graham did for her son in that video. Maybe we had more support than she does. Maybe we had less. Either way, I know my mom did everything she could–beginning long before I was a teen.

My mother did way more than keep me from dying. She made me succeed at living.