What tornado season looks like in eight seconds

It’s that time of year again when flowers bloom, ice starts to find its way into coffee, and afternoon strolls are a must. Ah, spring.

It’s that time of year again when flowers bloom, ice starts to find its way into coffee, and afternoon strolls are a must. Ah, spring.

Yet for all the wonders warmer temperatures can bring, there are a few downsides. Allergies for one. But those are just a minor nuisance compared to severe weather and the tornadoes it can spawn that generally occur with increasing frequency as the calendar turns.

Severe weather—huge storms that bring rain, hail, and lightning—are the product of warm, moist air, and atmospheric instability. Add in a change of wind direction or speed at different heights in the atmosphere, and you have all the ingredients necessary to get tornadoes spinning. You can see the odds of how likely severe weather—and by proxy, tornadoes—is to form on a given day anywhere in the US in the GIF above.

Those atmospheric ingredients tend to come into play across the Southeast in March as warm, moist air flows up from the Gulf of Mexico and meets with cooler, drier air dropping down from the northwest. That’s why March is peak tornado season for that region, known as Dixie Alley.

From there, the pattern spreads north and west toward the heart of Tornado Alley in the Central Plains. The statistical peak of tornado season is June 12, with the bullseye square over Kansas; the risk of severe weather then continues through the summer before eventually petering out in October as the seasons change.

Not that the risk of severe weather disappears completely. Tornadoes can occur (and have done so) on any day of the year. A severe weather outbreak spawned 73 tornadoes, including two EF-4 tornadoes with winds in excess of 190 mph in the Ohio River Valley in November 2013.

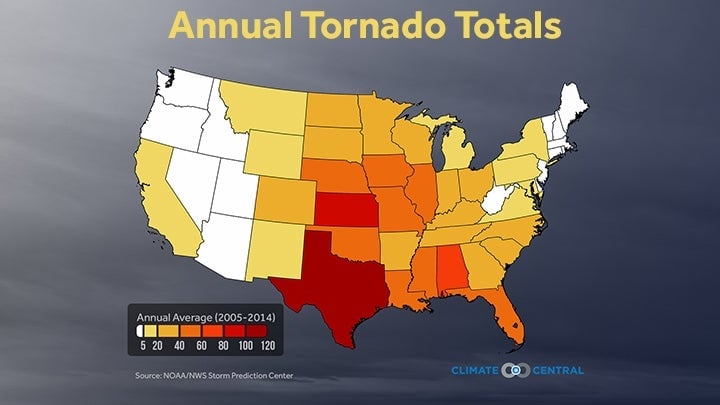

When it comes to the most tornadoes by state, don’t mess with Texas. The state sees an average of 112 tornadoes a year, due to its location in Tornado Alley and its large size. Tiny Rhode Island and Delaware tie for the states with the fewest with a big ol’ goose egg.

Beyond year-to-year variability, changes appear to be afoot for the tornado season. For one, the peak of tornado season in Tornado Alley is coming a week early now compared to 60 years ago, according to recent research. The exact reason for the shift is unknown, though it’s possible climate change could be playing a role.

In addition to a shift in the peak of tornado season, research has also shown that major outbreaks of tornadoes are becoming more common and that more tornadoes are occurring on those days.

This shift might have a stronger climate change connection. One of the leading hypotheses is that while warming throughout the atmosphere can make it more stable (bad news for tornadoes), it also means the atmosphere can hold more moisture (good news for tornadoes). That translates to a standoff on quiet days, but when moisture and instability break the gridlock, storms have more moisture at their disposal to ramp up and spawn more tornadoes.

Following an extremely active and deadly year in 2011, the US has seen a major lull in tornadoes. This year is no exception, with relatively few tornadoes touching down. As of April 30, the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) estimates that 226 tornadoes have formed, less than half the average of 498 for this time of year. The SPC also went three weeks into March before issuing its first severe weather watch, the longest March stretch on record going back to 1970.

Yet despite quiet years numbers-wise, there have been some extremely destructive storms, notably the November 2013 outbreak and the May 2013 outbreaks that spawned the El Reno and Moore tornadoes.

This post originally appeared at Climate Central.