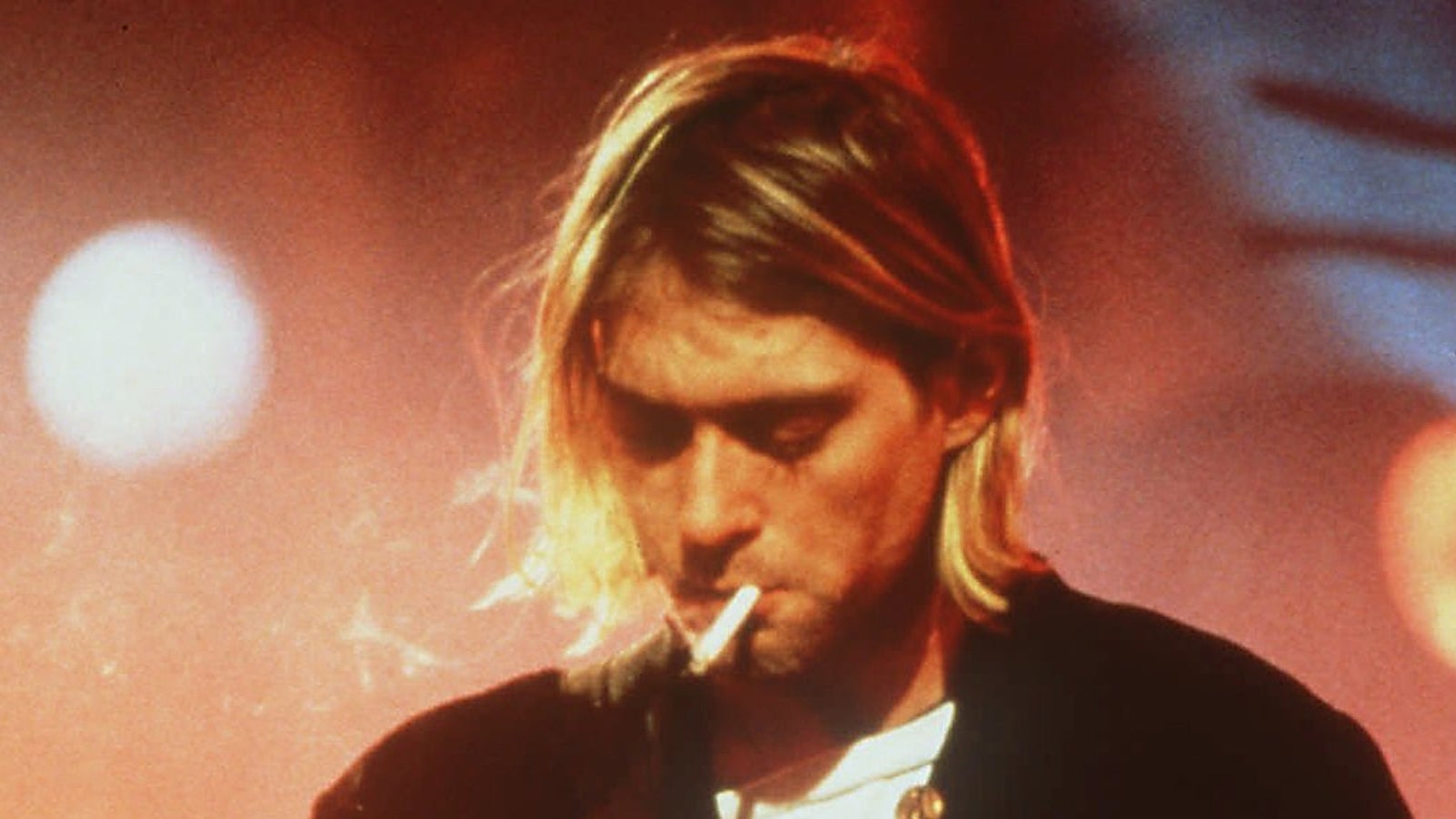

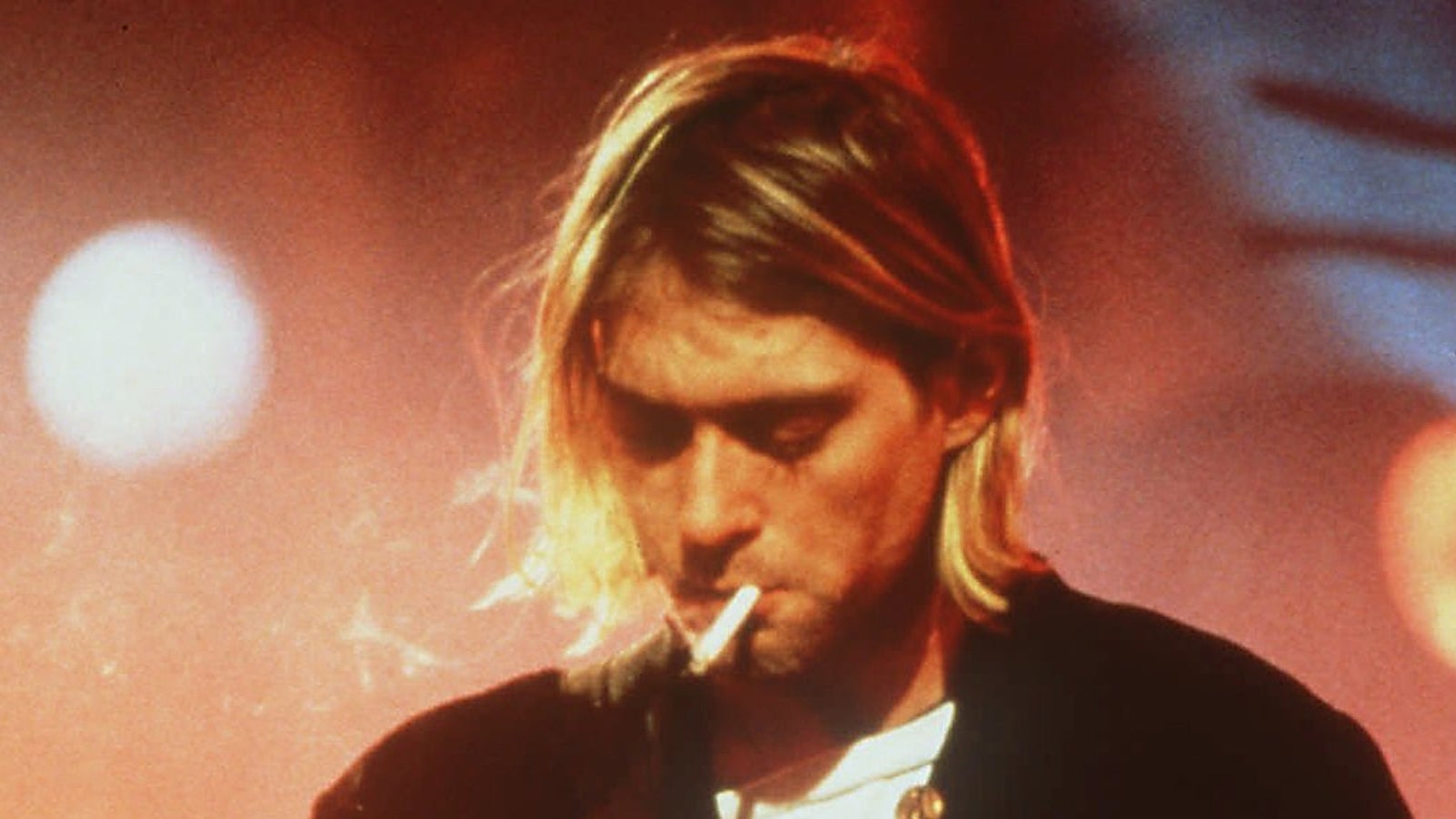

Kurt Cobain would probably hate the way his death has overshadowed his music

The myth surrounding Kurt Cobain casts him as a songwriting genius, rising to international fame while simultaneously—but also problematically—unwaveringly devoted to punk rock authenticity. He unwillingly and reluctantly became the voice of a generation, and he hated the rockstar fame and adulation that came with it. During the last couple years of his life, he was addicted to drugs, in part using them as a way to escape the pressures and perhaps even disappointments of stardom.

The myth surrounding Kurt Cobain casts him as a songwriting genius, rising to international fame while simultaneously—but also problematically—unwaveringly devoted to punk rock authenticity. He unwillingly and reluctantly became the voice of a generation, and he hated the rockstar fame and adulation that came with it. During the last couple years of his life, he was addicted to drugs, in part using them as a way to escape the pressures and perhaps even disappointments of stardom.

Success, the myth has it, drove Kurt to depression and ultimately to suicide—the ultimate rejection of fame. A new HBO documentary, Montage of Heck, attempts to probe beyond the often-romantic hero worship of Cobain to get to the real Kurt. Director Brett Morgen was granted first-time access to a rich collection of Cobain’s personal materials, including hundreds of tapes. We can also expect the release of an album that pulls together some of these lost recordings.

Rock documentaries tend not to focus on music-historical continuities and stylistic connections, and when they do, the observations are often simplistic, superficial or even incorrect. The worst in this regard tend to be the VH-1 Legends and Behind the Music episodes, but even the otherwise fantastic Beatles Anthology devotes proportionally little time to the band’s music. The problem is documentaries don’t focus on the music because they need to appeal broadly. But from the perspective of music history, the subject’s celebrity and personal life ends up being a relatively minor concern. After all, it’s the music that will survive.

And yet, artist documentaries do generally concentrate, instead, on the personal lives of their subjects; the more troubled those lives are, the better. Such films are most powerful when they highlight dramatic and titillating personal struggles and events. They are the least appealing, by contrast, when they spend a lot of time talking about the music. Music can certainly create celebrity, but then it turns out that celebrity is the more interesting thing to talk about.

I strongly suspect that Kurt Cobain would have preferred us to concentrate on the music, along with the cultural and historical contexts around it. Fifty years from now, the sensational details of Kurt’s personal life will be a biographical footnote, while the band’s music will live on.

For music historians, Cobain and Nirvana are mostly important for the group’s major-label debut, Nevermind, which rose to the top of the charts in early 1992, displacing Michael Jackson’s Dangerous for the number-one slot, and signaling a fundamental shift in pop music. It was, not to put too fine a point on it, the mainstream arrival of alternative rock. As interesting as the album is in itself, it is perhaps more significant for the commercial doors it opened for other alt-rock bands, acting much as the Beatles’ “I Want To Hold Your Hand” did to launch the British invasion almost 30 years earlier.

The emphasis is often on how Nevermind disrupted and re-directed rock history. Viewed from a larger music-historical distance, Cobain’s music also seems more continuous with the music that preceded it than it did back in the mid 1990s.

While Cobain himself was eager to point to influences from the punk scene from the late 1980s, his music also resonates with a wide range of even earlier artists. Kurt’s lyrics are filled with a kind of playfulness and fascination with wordplay that can be found in the lyrics of John Lennon (“I Dig A Pony,” “Mean Mr. Mustard”), Bob Dylan, and even Chuck Berry.

Nevermind producer Butch Vig remembers that all it took to get Kurt to double his vocals or add a harmony in the studio was to say, “John Lennon did it.” Kurt quickly obliged. His rebelliousness is reminiscent not only of the Ramones and the Sex Pistols, but also of Pete Townshend and the Who in the mid 60s. Kurt once wrote, “I hope I die before I turn into Pete Townshend,” a reference to the famous line in “My Generation.” And Kurt loved pop, at one point enthusing over the album, Get the Knack, while also having fun twisting the title of the hit single, “My Sharona.” A crucial and central element in the Nirvana story is how the band re-fashioned elements drawn from rock’s long history into a style that changed that history.

Montage of Heck may help viewers see beyond the Cobain myth. That myth, however, has had enormous staying power, and partly because it resonates within rock history. Cobain’s early death is much like those of Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin (all died at 27), feeding the popular fascination with untimely demise. The element of depression reminds us of Marilyn Monroe or Brian Jones (and there are many more).

Some have openly speculated that Cobain was clinically depressed, a condition that went back years before his drug addiction, and was almost completely undiagnosed and untreated during his lifetime. If so, it suggests that Cobain’s tragic death was not heroic in its rejection of a life of fame: What was heroic was that he held out so long against the darkness.