How Liberia finally got rid of Ebola

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that the Ebola outbreak in Libera is over, which means there haven’t been any new cases for the past 42 days. But the country remains on high alert, as new Ebola cases are still being reported in neighboring Sierra Leone and Guinea.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that the Ebola outbreak in Libera is over, which means there haven’t been any new cases for the past 42 days. But the country remains on high alert, as new Ebola cases are still being reported in neighboring Sierra Leone and Guinea.

Stamping out an epidemic of a deadly infectious disease is a great achievement for any country. Liberia’s triumph is more remarkable still given the country’s poor access to healthcare.

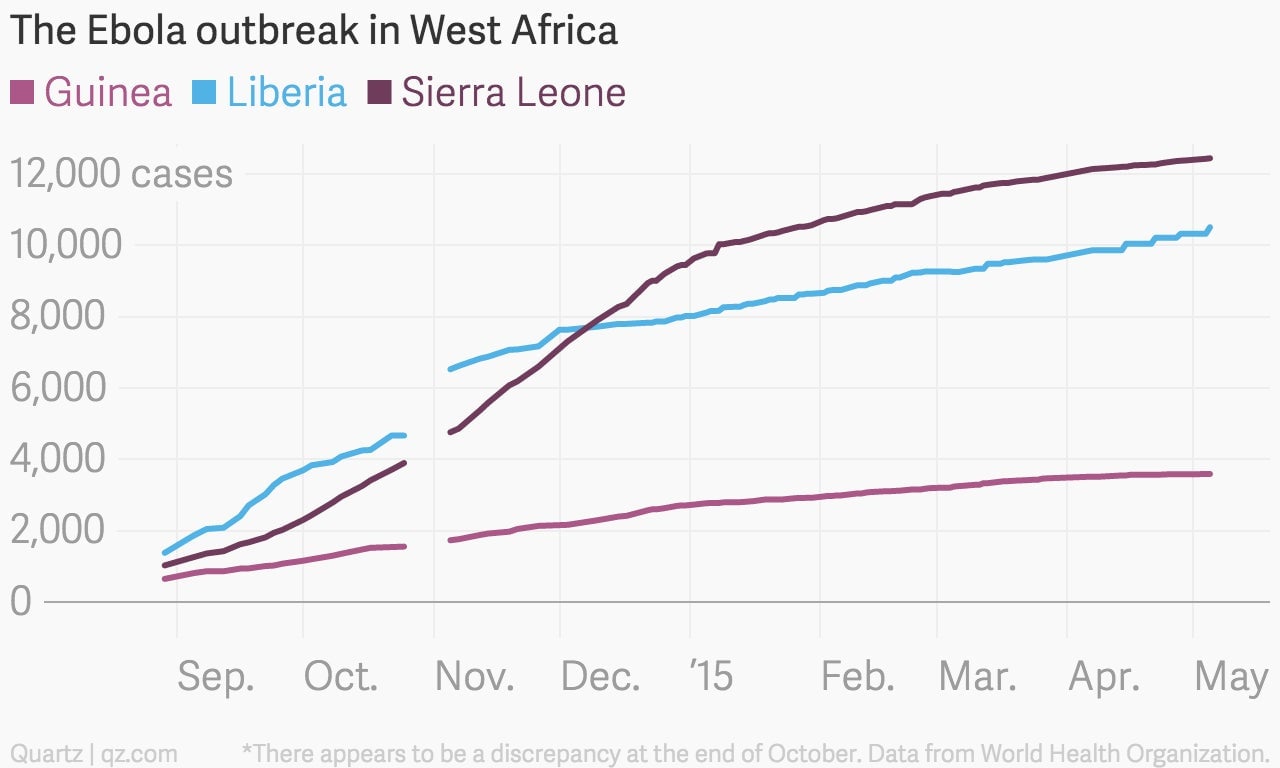

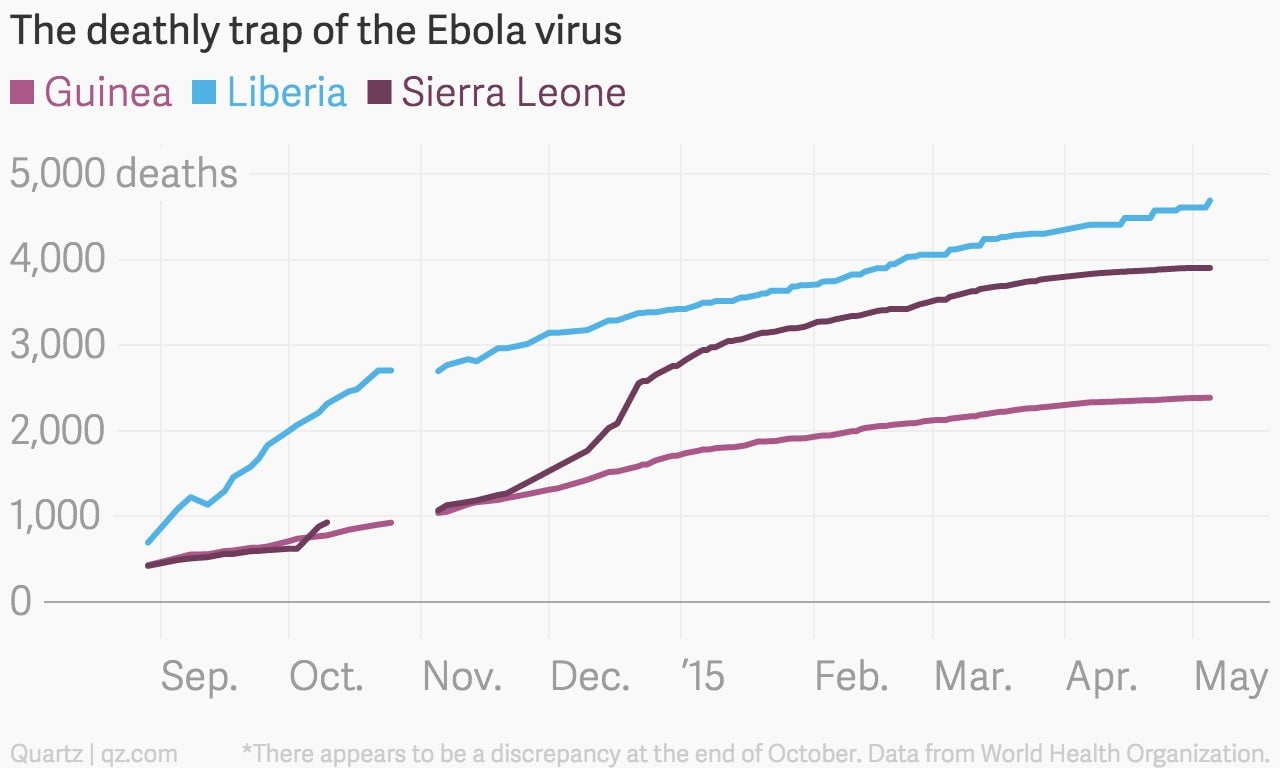

Although Liberia reported fewer total cases than Sierra Leone during the 15-month-long epidemic, it was the hardest hit of the three West African countries. As of May 8, Liberia counted 4,716 Ebola deaths, compared to 2,387 in Guinea and 3,904 in Sierra Leone.

The WHO gives three reasons for Liberia’s success. First, president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf made tough, aggressive decisions to control the spread. Second, the pace with which community engagement initiatives helped spread health information and got people to work together. And, third, the successful integration of international partners in combating the epidemic.

Liberia’s achievement raises hopes for Sierra Leone and Guinea, where only nine new cases were reported in the week of May 3. In these countries, Ebola’s geographic spread is now much more contained than it had been at the epidemic’s peak. However, the onset of the rainy season—which can make it even harder to access healthcare and maintain good hygiene practices—means controlling new cases in remote areas will be increasingly difficult.

There is also the problem of complacency among people in Sierra Leone, according to a recent report by medical researcher Mark Honigsbaum. Even desperate efforts, such as Sierra Leone’s nationwide 72-hour lockdown in March, haven’t brought the number of new cases to zero.

The biggest challenge to overcome, however, is going to be “hidden” cases. Whenever a new Ebola case is detected, healthcare workers scramble to trace anyone who came in contact with the infected person during the previous 21 days, which is the amount of time the virus takes to show symptoms.

During the peak period of the disease, perfect tracing was near-impossible, and healthcare workers had to deal with many hidden cases. With fewer patients to handle, this should become easier. But, sadly, in Sierra Leone and Guinea, new Ebola cases among those not on the contact list have still been emerging.

“We may have stopped the hotspots,” Rajesh Panjabi, chief executive of Last Mile Health, a non-profit organization working in Liberia, told Nature. “But the blind spots—remote villages with little or no access to healthcare—still exist.”