Potwallers and Suffragettes: a very short history of UK electoral reform

Back before 1832, it wasn’t easy to vote in the UK. Firstly you had to be a man; secondly, you had to own enough property to prove you had a “stake” in the country. There were some rough-and-ready ways found to extend the franchise: like the granting of voting rights to “potwallers”—men who lodged in the house of someone else, but had the distinction of a separate cooking fire on which to boil a pot.

Back before 1832, it wasn’t easy to vote in the UK. Firstly you had to be a man; secondly, you had to own enough property to prove you had a “stake” in the country. There were some rough-and-ready ways found to extend the franchise: like the granting of voting rights to “potwallers”—men who lodged in the house of someone else, but had the distinction of a separate cooking fire on which to boil a pot.

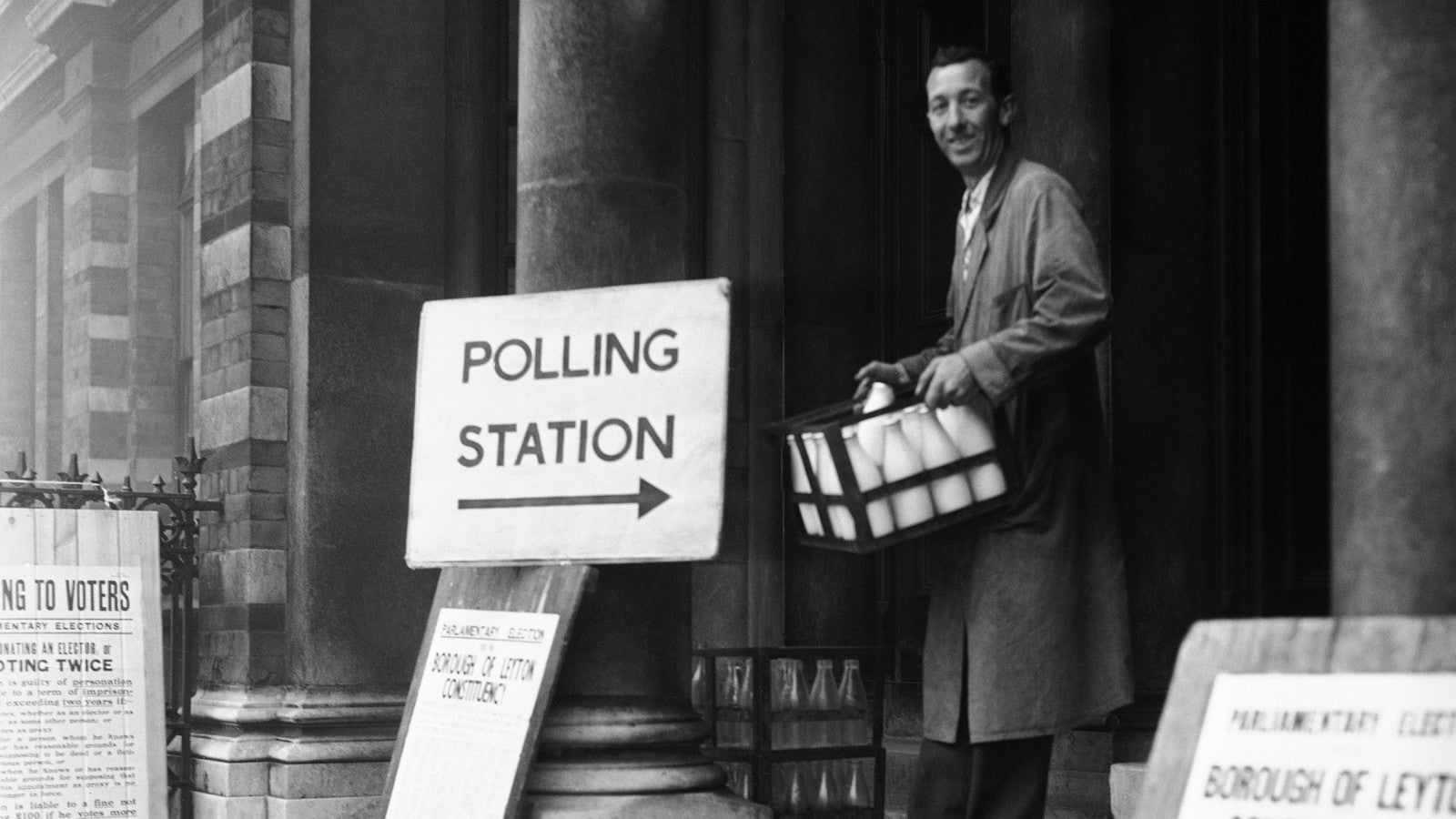

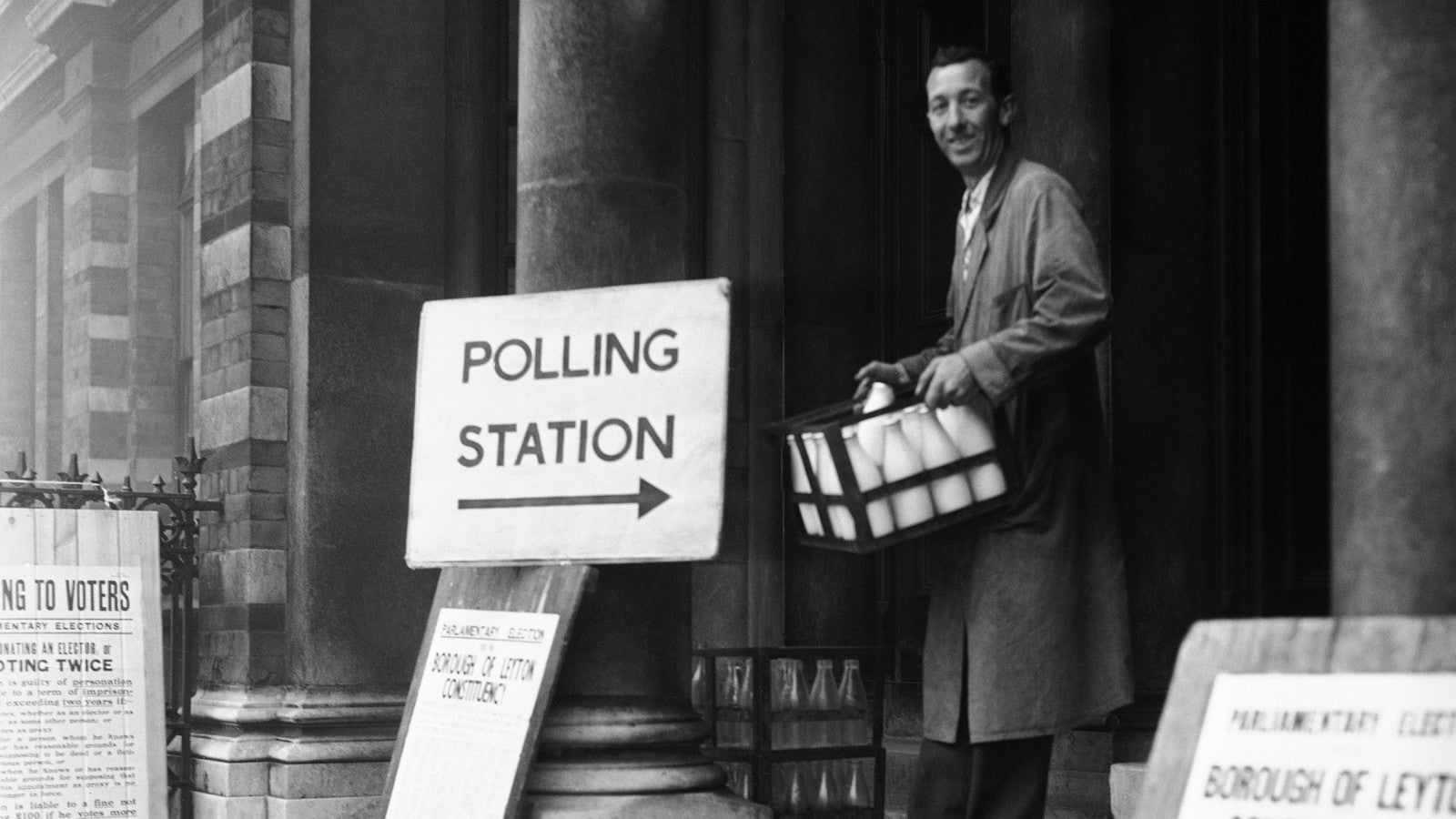

The UK’s “first past the post” plurality system divides the country into 650 separate races for a seat in parliament, rather than apportioning votes to candidates or parties on a proportional system. Last week’s election delivered what many see as a characteristically unrepresentative result, this time skewed because votes for smaller parties weighed so heavily in some areas and not at all in others.

Reform of the electoral system, a point of bitter contention throughout the 1800s and early 20th century, is back up high on the agenda. So how did we get where we are?

In the 18th century, Europe comprised a set of kingdoms, and democracy was nothing more than a distant dream, if it was thought of at all. The French Revolution of 1789 changed that, sparking real discussion of how to make government more equitable.

The UK’s parliament was controlled by wealthy landowners and its electoral system was designed to keep them in power. The 1832 Reform Act enfranchised some more men and started to dismantle a system skewed by “rotten boroughs”—areas that could sometimes elect several members of Parliament but which contained barely any voters. A series of reforms strung out over the next 86 years extended the franchise, eventually, to all men over the age of 21, made ballots secret, and redefined constituency borders to make them more representative.

The early 20th century was punctuated by increasingly violent struggles for female suffrage, but not until the end of the First World War, in 1918, did some women get the vote. Ten years later, they were granted rights on the same basis as men: at the age of 21, regardless of property ownership. In 1969 the voting age was reduced to 18.

The first past the post system, meanwhile, has been the subject of debate for much of the later 20th century and early 21st. Critics say it delivers unrepresentative results and renders millions of votes wasted.

The Liberal Democrat Party finally succeeded in forcing a referendum on changing the electoral system in 2011, but both public understanding and turnout was low, and the idea was defeated. It’s now back on the agenda.

Still, since the status quo favors larger parties and one of them has just won a majority (while the Lib Dems, reform champions, have been crushed), change seems unlikely any time soon.