A team of scientists have engineered a chicken with a dinosaur’s face to study evolution

At some point 150 million years or so ago, a certain set of dinosaurs started to look more and more like what we now know as modern birds. One of the most pronounced changes occurred in the front of the face: the nascent birds lost their teeth and the small bones that once sat at the tip of the snout fused and elongated into the modern beak.

At some point 150 million years or so ago, a certain set of dinosaurs started to look more and more like what we now know as modern birds. One of the most pronounced changes occurred in the front of the face: the nascent birds lost their teeth and the small bones that once sat at the tip of the snout fused and elongated into the modern beak.

But how, exactly, did this happen?

To find out, researchers from Harvard and Yale decided to back-trace the development of the beak themselves. And in doing so, they created a sort of dino-chicken: an embryo whose snout lies somewhere between that of a regular chicken beak and that of a pre-historic archosaur—the dino precursors to birds. The resulting paper is published in the journal Evolution.

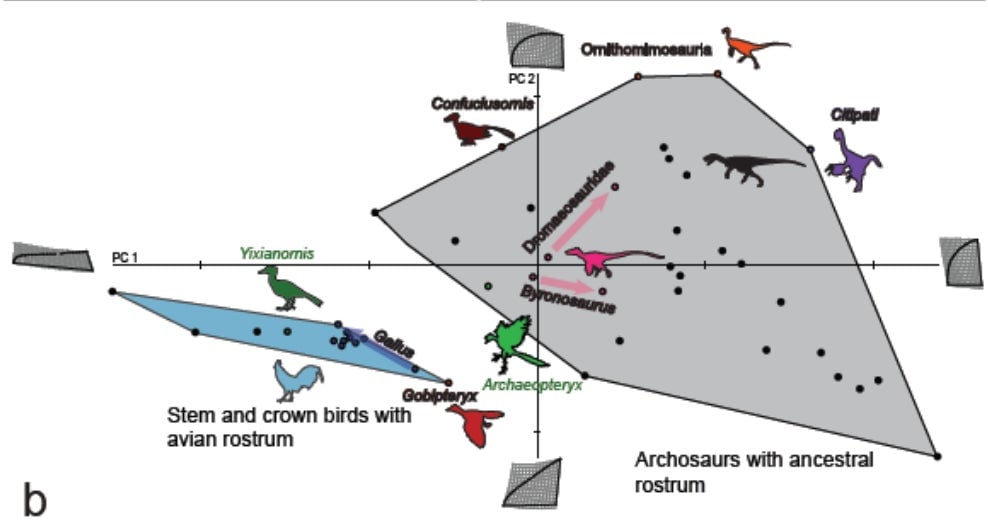

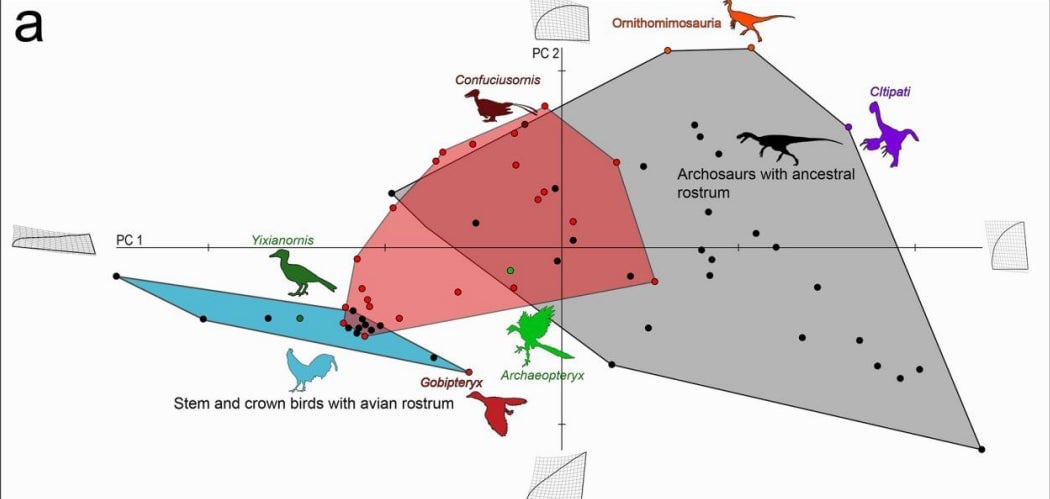

The first step in the research was to determine how the rostrum (a more general term for a beak-like or snout-like projection) changed in different species over time. The researchers were able to separate the physical characteristics into two general categories: the birds and the dinosaurs.

The researchers then tracked the development of bird beaks to parts of two genetic pathways known as FGF and WNT. At the points in a chicken’s embryonic development that those pathways would typically be triggered, they implanted a bead soaked in inhibitors into the embryo’s face.

When they examined the results close to the hatching point, they found that many of the modified embryos looked markedly different than typical chickens. The rostra fell somewhere in the middle ground between modern birds and archosaurs (results are shown in red):

Here’s a photo comparing the skulls of a modified and unmodified chicken embryo with that of an alligator, an archosaur descendant that evolved down a different path:

The results suggest that the pathways identified by the scientists evolved on one side of the archosaur family tree, but not the other, and that these pathways are the basis for beaks. Moreover, because the modified chickens actually lie somewhere in between dinosaurs and modern birds, the scientists think it’s likely we’ll one day find fossils of animals that look like the modified ones: an animal somewhere at the evolutionary midpoint between dinosaurs and birds.

This type of genetic modification might seem strange, particularly since it’s closely related to dinosaurs, conjuring images of Jurassic Park. But in fact, scientists have been genetically modifying animals for research purposes for years. The 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for example, was awarded for the discovery of a substance called green fluorescent protein, or GFP, which has since been used to genetically create glowing pigs to study medicine-delivery systems and glowing cats to study HIV.