I travelled across China photographing families with everything they own

When I was about five, my parents took me to live in the city. At the time, people did not think to buy houses—we lived in a 20 square meter apartment allocated by the factory where my parents worked. The apartment had one large bed, one small bed, a table, and four chairs.

When I was about five, my parents took me to live in the city. At the time, people did not think to buy houses—we lived in a 20 square meter apartment allocated by the factory where my parents worked. The apartment had one large bed, one small bed, a table, and four chairs.

Since the factory was state property, so were these—and they were by no means our own. If we ever needed anything else, we could apply to the factory support office. Later, my father bought a tube radio for 10 yuan from the consignment store—our very first “belonging.” That year, his monthly salary was only 48 yuan (about $112 in today’s dollars).

In 1977, my father spent 100 yuan ($238 today) to have a large wardrobe made; it had two doors and several drawers, and when we got it home, all of our neighbors were deeply envious. That was our first piece of furniture.

In 1978, the newly reformed Chinese television system broadcast an American television series called Garrison’s Gorillas. Every evening the children of our courtyard would run to the neighbors’ house, and cram themselves in front of the TV. One time, my brother and I were shooed away. After our father found out, he went to the TV factory in Luoyang and bought a black and white tube TV—and to add a little color also bought a tricolor film to stick on the screen. A month later, after Garrison’s Gorillas had finished its broadcast, my father took the TV set back.

When my father and uncle began to live separately from my grandparents, they divided up our family assets, and all my father received was two kilograms of soybeans. By the time I graduated in 1980, our entire collection of family belongings was worth a total of less than 800 yuan ($2,109 today).

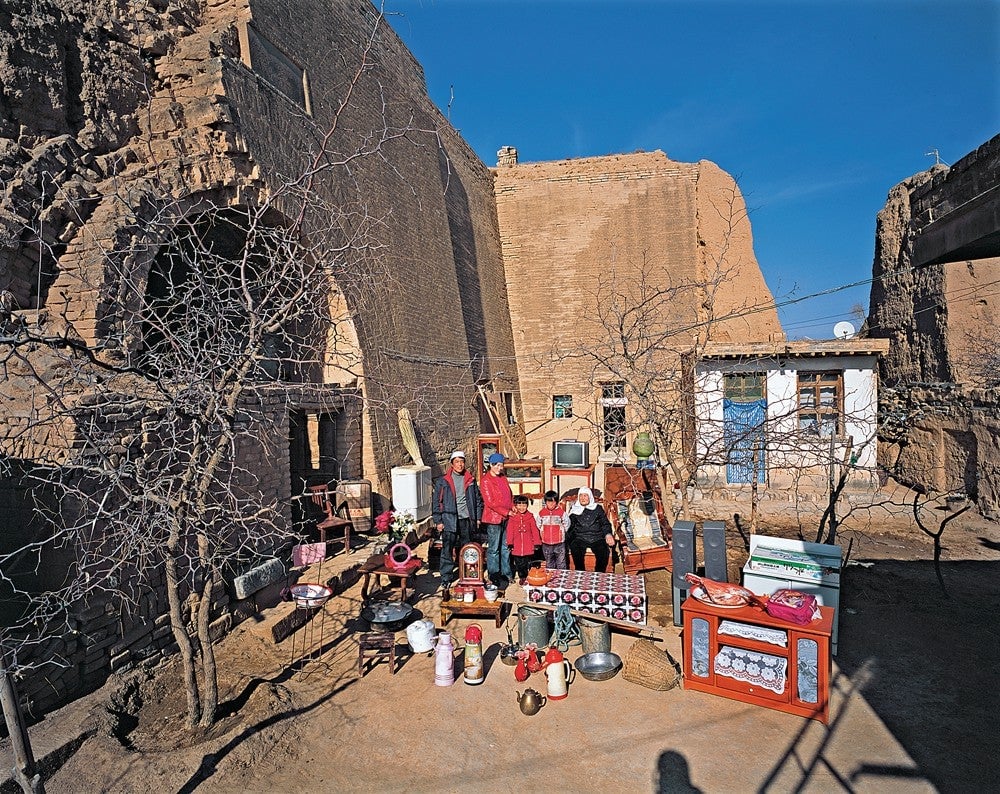

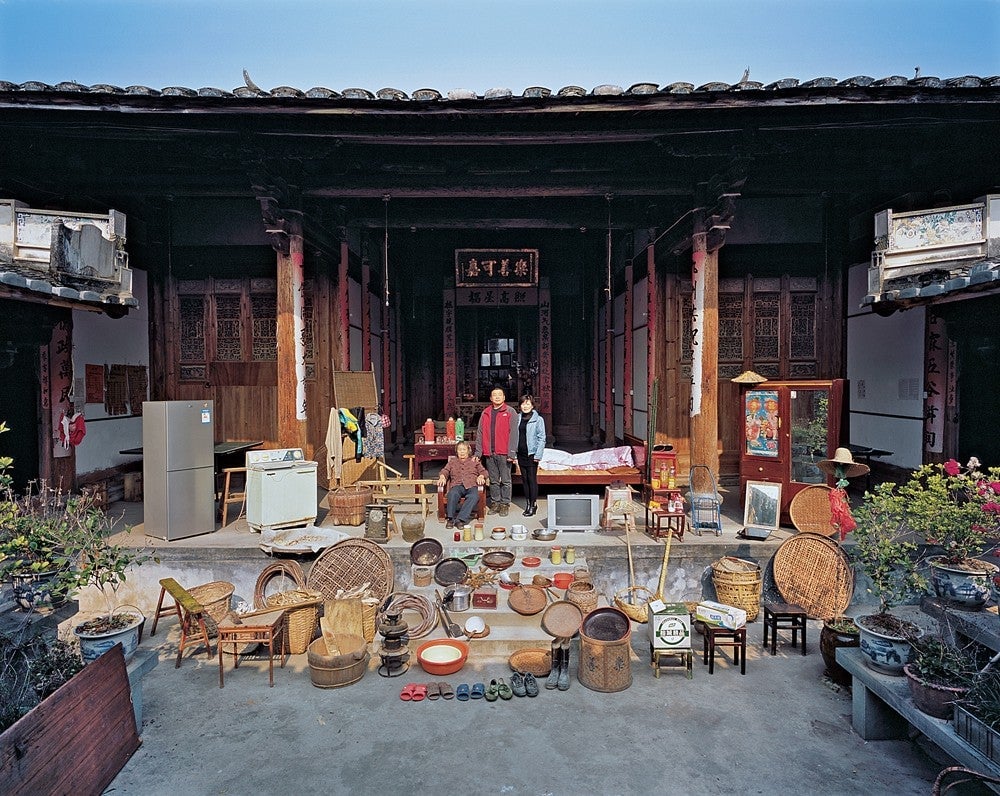

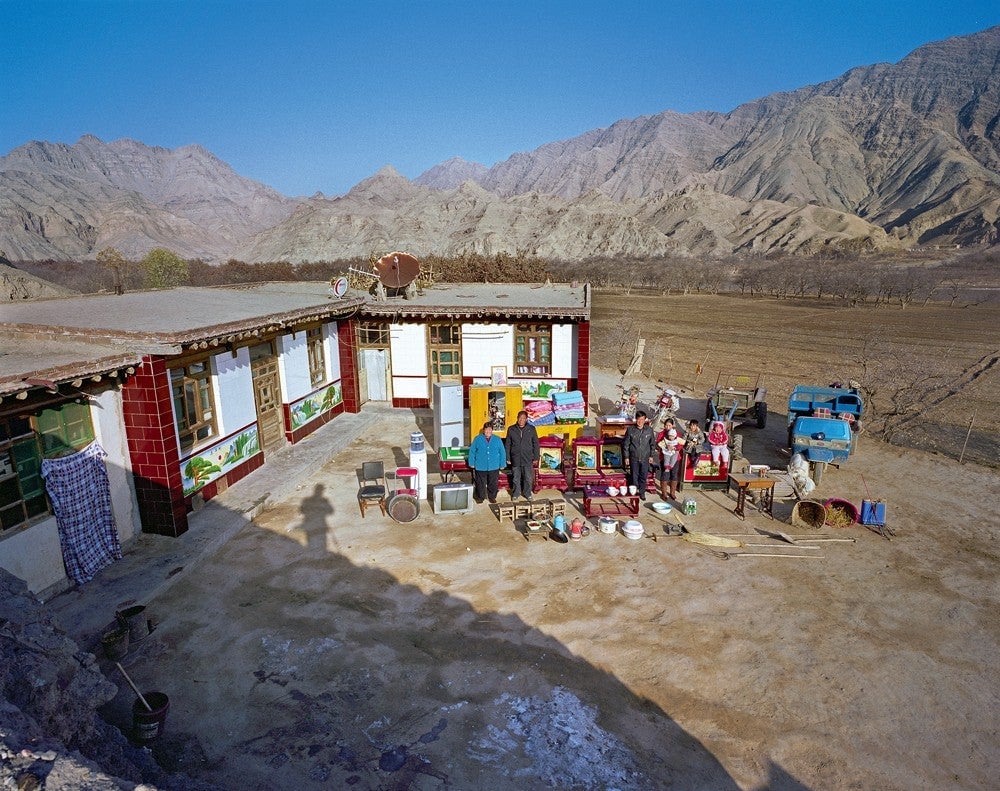

For this series of photos, called The Family Belongings of Chinese People, I mostly chose to photograph the homes of common families, who form the vast majority—and most fundamental element—of Chinese society. Since the items aren’t of much value, these families were willing to take them out and show them to others.

I also wanted to take some photos of the family belongings of wealthy people, like heads of coal mining companies, but this proved very difficult. They weren’t willing to let other people see what sort of things they had in their homes. Of course, they are their own private belongings, and the choice is entirely up to them.

A nation’s assets are its people. The people’s assets are represented in the things they own, and these are recognized and protected by national security.

As I write this, I am currently on a flight to Canada, passing over eastern Russia’s Sakhalin Island. My good friend Zhao Rongsheng is next to me, reading the Diamond Sutra, which he does every day. When I ask him how he feels after reading it, he tells me, “a sense of belonging.”

Most of the passengers are Chinese—about half are Chinese immigrants living in Canada, and the other half are visiting relatives or vacationing. I’m using my vacation to go some place quiet and relaxing for a while. The Chinese passengers with Canadian citizenship probably have a sense of returning home, since both China and Canada are home to them. Traveling from one to the other is an easy and pleasant transition.

In the more than three decades since China opened up, the resulting social transformation has led to problems like pollution and economic imbalance. Large numbers of more wealthy people have begun to leave the country.

Before the plane begins to descend, the attendant comes around with drinks, and a nearby Chinese passenger asks if the apple juice was produced in China or Canada. The attendant emphasizes that it’s from Canada. After accumulating a certain amount of wealth, many Chinese citizens have started to pay more attention to developing better lifestyles and living environments.

A first-class ticket on this flight costs more than 30,000 yuan ($4,800); the passenger next to me says that the only benefit of first class is that you get to sleep better, and that there’s no way 30,000 yuan is worth it. But after the 12-hour flight is over, you wake up and think about how great it is to be able to spend this time sleeping in a proper position.

Now as I board the flight back to China, another Chinese person sees that I have a lot of luggage, so he asks me if I’m going home. I say yes. What is home? I think home is the place that you came from, and that you miss after you leave it. So in a sense, the family belongings in these pictures are a form of “home.” It has taken me 10 years to photograph them all.

This post originally appeared on photographer Ma Hongjie’s blog, where you can find many more photos from his series The Family Belongings of Chinese People.