Nepal’s devastating earthquake underlines the risks of China’s Tibet dam-building binge

The earthquake that rattled Nepal on April 25, killing thousands, also cracked a huge hydroelectric dam and damaged many others. Things could have been much worse, though. The collapse of one of these could have let loose a deluge of water and debris downstream, as Isabel Hilton highlighted in the New Yorker—a disquieting prospect given that more than 400 dams are being built or are slated for construction in the Himalayan valley.

The earthquake that rattled Nepal on April 25, killing thousands, also cracked a huge hydroelectric dam and damaged many others. Things could have been much worse, though. The collapse of one of these could have let loose a deluge of water and debris downstream, as Isabel Hilton highlighted in the New Yorker—a disquieting prospect given that more than 400 dams are being built or are slated for construction in the Himalayan valley.

This underscores the risks of China’s recent push to dam rivers in Tibet. Threatened by a lack of natural energy sources, the Chinese government has been on a dam-building bender. China now has more installed hydropower capacity than the next three runner-up countries combined.

But the government has only just begun to harness the power created as runoff from Himalayan glaciers flows across Tibet, plunging around 3,000 meters. The biggest of these rivers, the Yarlung River (a.k.a. Yarlung Tsangpo, Yarlung Zangbo), cuts along the bottom third of the autonomous region before hanging a sharp right into India and Bangladesh, where it’s called the Brahmaputra. In November of 2014, the government unveiled Tibet’s first truly huge hydropower project—a 9.6 billion yuan ($1.6 billion) project spanning the Yarlung River’s middle reaches, called the Zangmu dam.

Unfortunately, like much of the rest of the Himalayan valley, the bedrock around the Yarlung River is unusually tectonically active. Worse, the weight of dammed reservoirs has been linked to more than 100 earthquakes (paywall), most notoriously, the 2008 earthquake in nearby Sichuan, which killed around 80,000.

Why take the risk? The Chinese government says the hydropower projects will solve Tibet’s electricity shortages. But it’s not clear Tibetans actually need it.

The region surrounding the Yarlung River has too few people and too small an economy to require all that electricity, Fan Xiao, geologist and chief engineer at the Sichuan Geology and Mineral Bureau, told chinadialogue. A rough calculation suggests he’s right. The Zangmu dam will provide 2.5 billion kilowatt hours of electricity a year. That’s around 80% of what Tibet consumes in total—and four more dams are in the works for other sites along the Yarlung River.

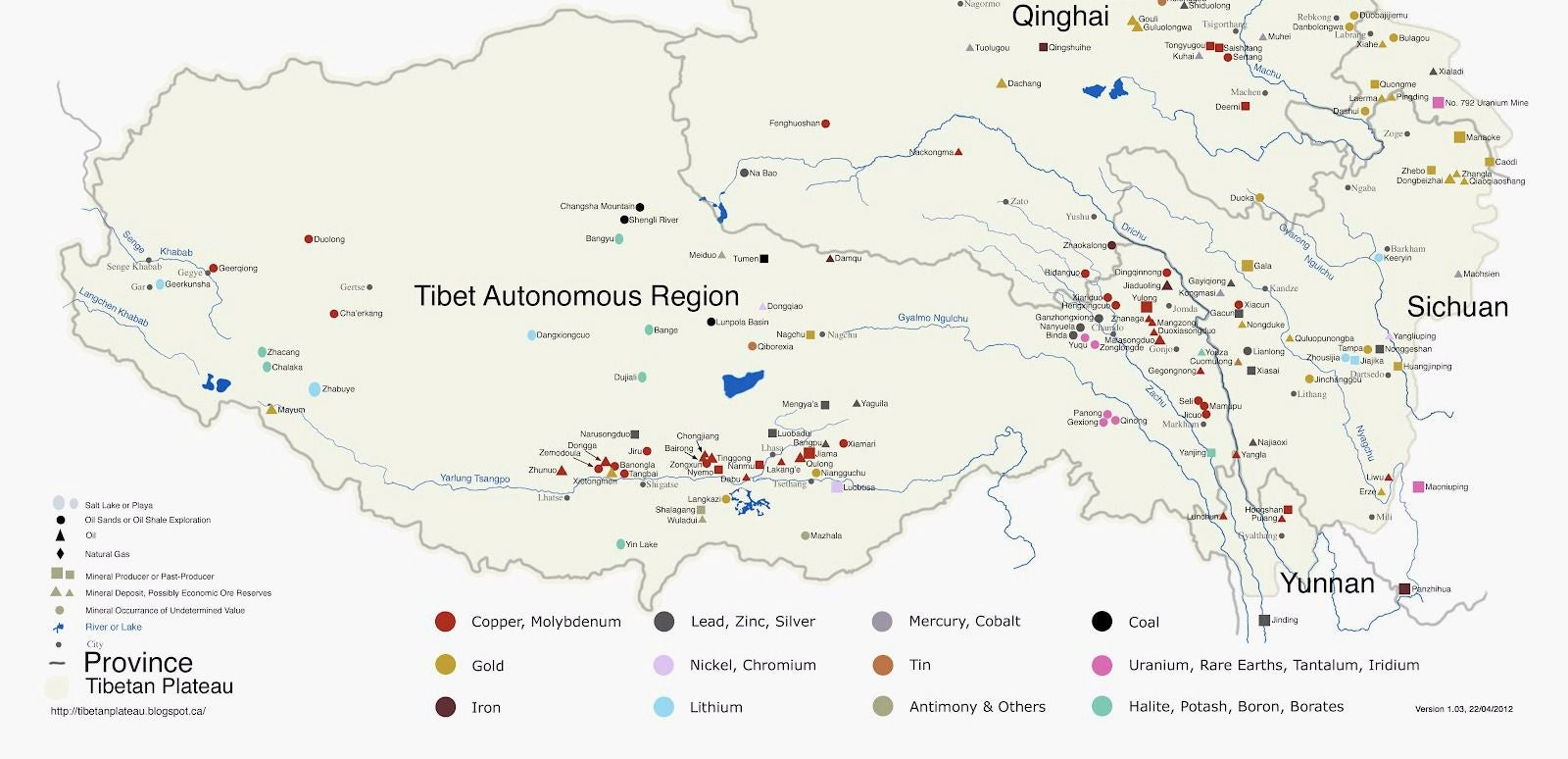

Mining companies probably need that electricity more than nomadic herders. Among Tibet’s bounty of natural resources, a significant share of its gold and copper mines sit within convenient reach of current or planned Yarlung River hydropower stations.

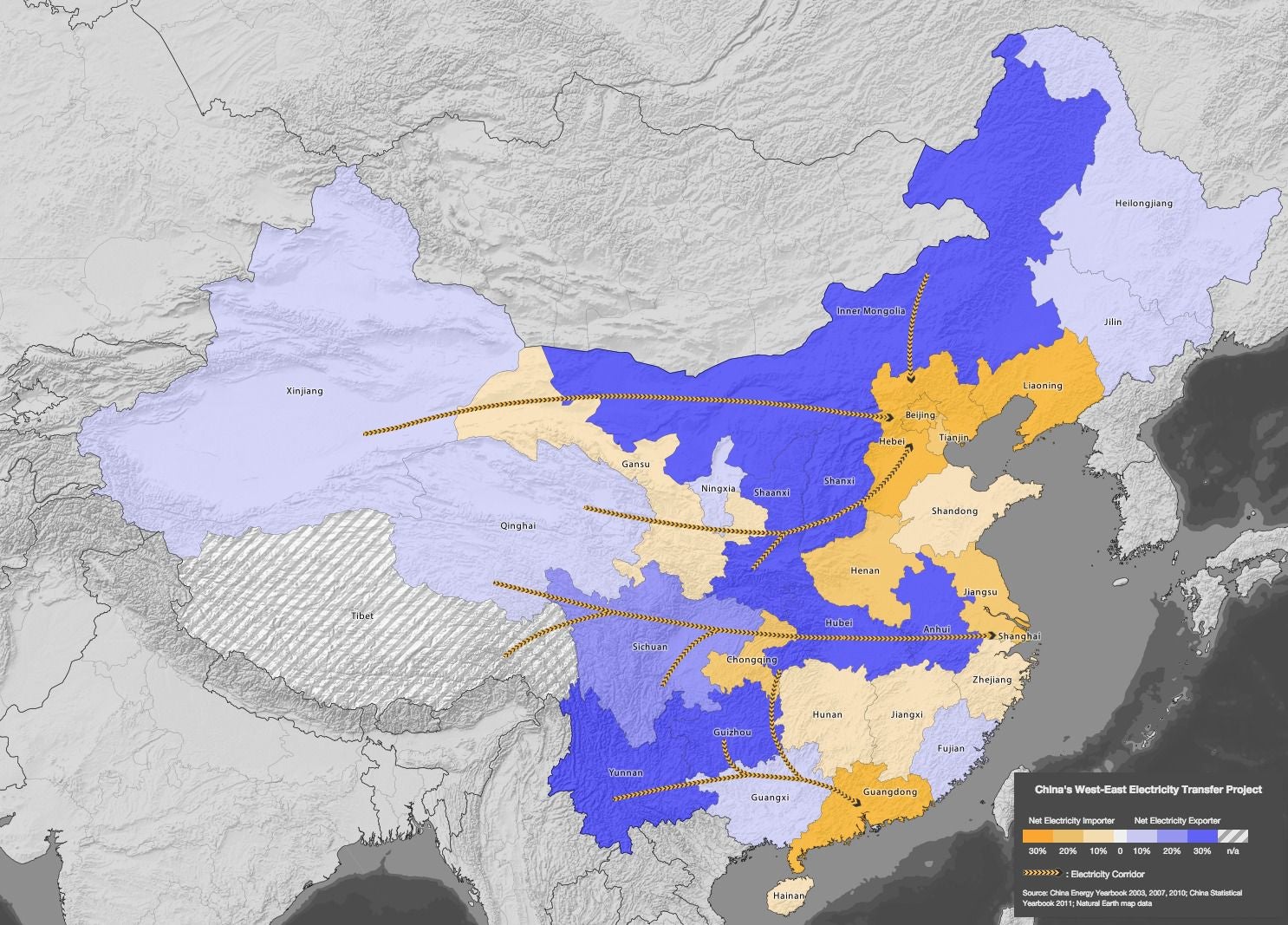

Other likely beneficiaries of Himalayan wattage are energy-strapped Chinese provinces to the east. Though Tibet has less than 0.25% of China’s population, it holds around three-tenths of its water power resources. The government has long planned to turn Tibet into a base for the “West-East Electricity Transmission Project,” shunting energy from China’s resource-rich western regions to the coastal provinces, which are far more industrialized yet also resource-scarce. This map from Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum shows how this will work:

This hints at ugly odds behind China’s dam-building frenzy in Tibet. A single earthquake, let alone dam collapse, could devastate many in Tibet. Unfortunately for them, the ultimate winners of this cheap-power gamble will be too far away to feel it.