Mid-sized farms—and the local food you buy—are in danger

This will be a tough year for farmers—especially for those running mid-size farms.

This will be a tough year for farmers—especially for those running mid-size farms.

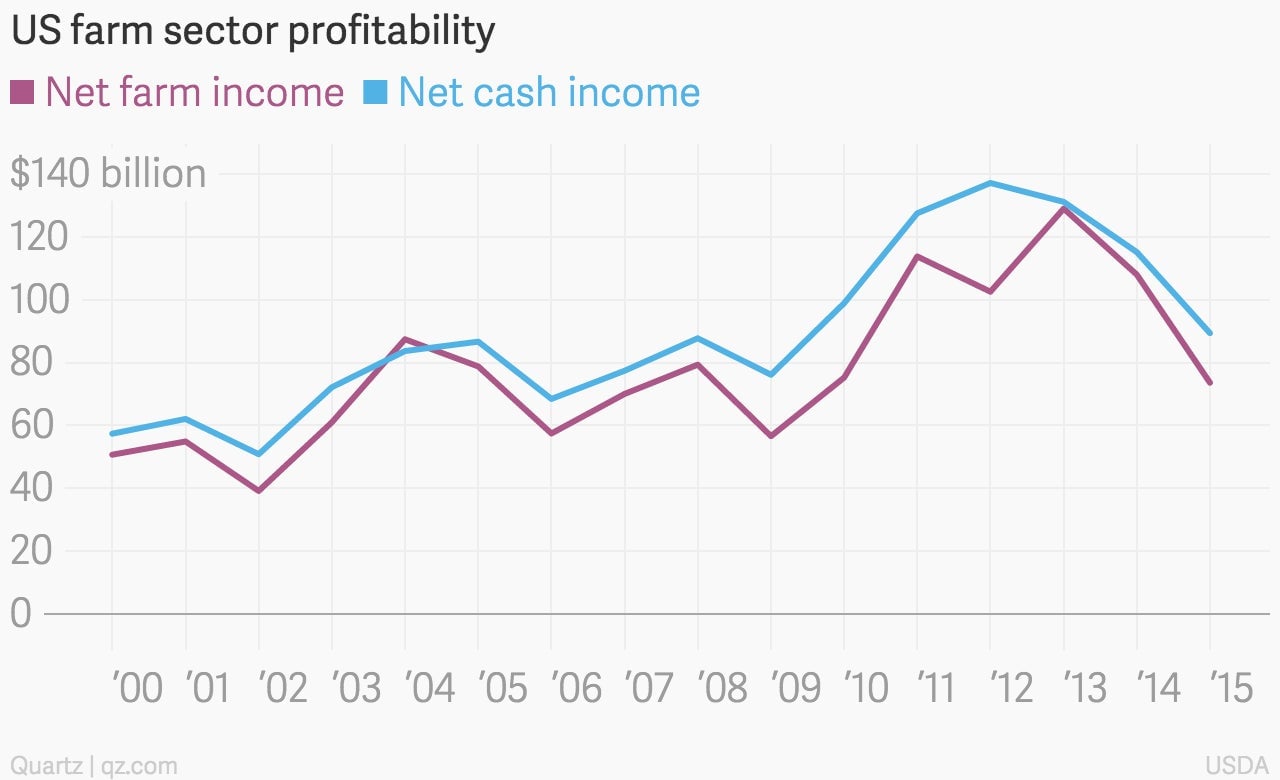

The US Department of Agriculture has released its projections for farm profitability in 2015 and the numbers are not encouraging. Net farm income, projected at $73.6 billion in 2015, is expected to fall 32% from 2014’s $108 billion. That is the lowest it has been since 2009, and a 43% drop from 2013’s record high of $129 million. Net cash income is also expected to fall to $89.4 billion, a 22% drop from 2014’s projection.

(While net cash income refers to basic cash accounting, net farm income is a better measure of profitability as it includes accrual adjustments like inventory value and non-money expenses such as providing housing for farm workers.)

The reason for the drop in profitability is simple: lower food prices. Even with the 2014 Farm Bill’s 15% increase in government payments to farmers, low corn, milk, and fruit/nut prices, combined with higher expenses, will make a dent on farms’ ability to make a decent profit.

But the pain will not be felt equally by all farmers, says Mitch Morehart of the USDA Economic Research Service. Of the country’s approximately 2.1 million farms, the vast majority—about 1.7 million— are considered small, meaning that they have less than $100,000 a year in sales, and don’t rely on farming as their primary source of income. “In fact, it’s usually negative,” says Morehart, “they take a loss from the farming income.” Because these farmers’ household income comes from their primary jobs, not farming, this drop in profitability is not going to have a real impact on them. “They’re rural residents who meet our definition of the farm, who have 30 cattle or 10 acres of corn,” says Morehart. “They’re not fully engaged in commercial agriculture.”

For larger commercial agriculture operations, says Morehart, “The depth and breadth of the impact depends on how each individual business is insulated against financial outcomes. Most are pretty well insulated. They don’t over-borrow, they don’t project abnormally high prices in the way they operate.”

The farms that will feel the crunch the most will be those that are already struggling to survive, the ones in the middle. The USDA doesn’t have an official definition of what counts as a “mid-sized farm”—the agency is working on defining the group now, Morehart says. But the website Grist explained it thusly in its excellent series, Farm Size Matters: “These are the farms that are too big and too busy to sell at farmers market, but too small to compete in an increasingly industrialized food system.”

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly how many mid-sized farms have gone out of business entirely in recent years, because some have grown into large farms and others have shrunk into small farms, but as Grist notes, “both gross annual sales numbers and cropland acreage stats show a hollowing out of agriculture of the middle.”

“Their profits either get bigger or smaller,” says Morehart. “Most get smaller, just reduce their footprint and find alternate income sources.”

This is bad news for anyone hoping to buy local food at the supermarket.