Chinese banks took the four top spots in Forbes’ list of the world’s most powerful companies

Yet another sign of China’s global domination: All but one of the five biggest, most powerful companies in the world are Chinese state-owned banks. That’s according to Forbes annual Global 2000 list, which measures public companies based on revenue, profit, assets, and market value.

Yet another sign of China’s global domination: All but one of the five biggest, most powerful companies in the world are Chinese state-owned banks. That’s according to Forbes annual Global 2000 list, which measures public companies based on revenue, profit, assets, and market value.

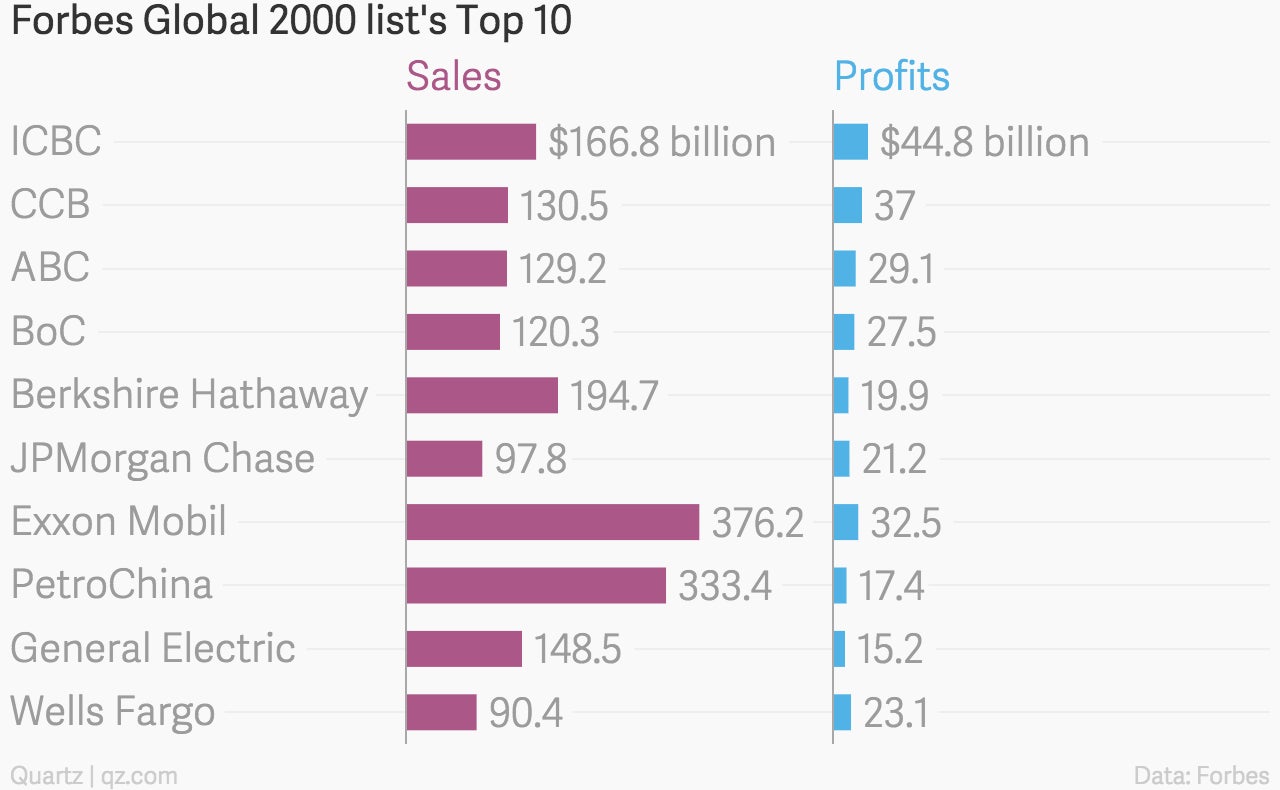

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and China Construction Bank (CCB) seized the top two spots in 2013, with Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) taking #3 in 2014. This year, Bank of China jumped five spots to oust JP Morgan Chase from the Top 5:

Based on banking assets alone, there’s a darker omen to read in the ascendance of Chinese banks.

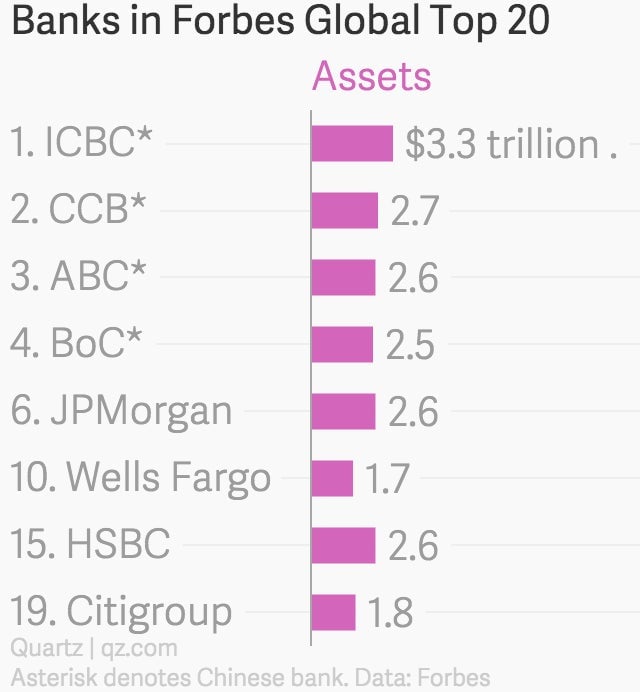

Of the eight banks in the top 20 spots of Forbes’ global ranking, four Chinese banks claim 56% of the total assets (and those assets are made up primarily of loans).

As it happens, in the late 1980s, a similar trend took hold: The world’s five biggest banks by total assets were Japanese. China’s not quite there, but it’s pretty close.

China’s bank bloat comes from the same investment-driven, industry-focused growth model once championed by Japan. As the Chinese government attempts to ditch this model, it faces many of the same challenges Japan did in the late 1980s:

- Banks as instruments of policy. Instead of allowing markets to set interest rates, the governments of both countries used state-run banks as the chief channels for money creation, subsidizing credit by keeping household savings deposits artificially low. Industrial policy mandated that the bulk of credit flowed to state-owned or state-affiliated companies. The political nature of these loans means rolled-over credit isn’t counted as “bad,” keeping banks’ non-performing loan rates spuriously low. Market reforms make it harder to sustain this fiction.

- Reform shrinks bank profits. This model long guaranteed easy profits for banks. In Japan’s case, the reversal of these policies resulting from financial reforms—notably letting the market set the deposit rate—swallowed up bank profitability, spurring riskier lending and investment. China is planning a similar suite of reforms, including lifting the deposit rate cap later this year.

- Faltering growth, easy money. Japan’s cratering growth prompted the central bank to cut interest rates starting in 1986, inflating the stock bubble that eventually burst in late 1989. With corporate profits sputtering, China’s central bank has loosened several times in six months. As most outstanding loans are pegged to the central bank’s benchmark lending rate, this is crimping bank profitability.

- Stock market boom. Securities reform and Japan’s surging stock market in the late 1980s meant companies could raise cash cheaply, rather than paying 5% interest on a bank loan. This, in turn, forced banks to issue riskier loans. China’s bull market, which began in mid-2014, and planned reforms could similarly disadvantage its banks.

In the case of Japan, the eventual result was economic collapse. The determining factor wasn’t the 1989 stock market crash or the housing bust. Rather, the country’s faulty growth model led to a long downward spiral of feeble growth, as Japanese banks—and the government—repeatedly failed to recognize the actual amount of bad debt, as we’ve discussed before. Perhaps Chinese banks will weather reforms better. If not, they will face the same fate as Japan’s shattered financial industry, which only had two banks in this year’s Forbes Top 100.