It’s the beginning of the end for coal in the US

This post originally appeared at InsideClimate News.

This post originally appeared at InsideClimate News.

If coal were a medical patient, its prognosis would be creeping toward the critical list.

Despite the major forces trying to align to save it, coal’s future as a major energy source is being attacked by a variety of pathogens: government regulations, market forces and moral arguments. As a result, government charts plotting coal’s life expectancy look like the flat vital signs of a very sick patient.

Those charts don’t even take into account President Obama’s regulation to crack down on carbon emissions from the nation’s nearly 600 coal-fired power plants, which will no doubt send the vital signs plunging.

The Energy Department’s statistical arm, the Energy Information Administration, forecasts in its its latest annual energy outlook that US coal production “remains below its 2008 level through 2040.” And that is without weaving in the impact of the Clean Power Plan, because it hasn’t yet taken effect.

For the next 15 years or so production might creep up, it said, but only by a fraction of a percent each year. Considering that production has dropped 16% between 2008 and 2013, that’s hardly a robust recovery.

And then the tepid growth evaporates away. From 2030 on, the report said, demand for coal from its main users, electric power companies, would be essentially flat.

Coal’s dwindling prospects reflect several main factors: the increasing weight of other environmental regulations, including new standards limiting mercury emissions and other toxic pollutants; the availability of cheap, relatively clean natural gas; steadily increasing energy efficiency, and the surging installations of renewable energy plants, especially wind and solar.

Agency officials have promised to produce another forecast later this month that will show how much coal production might vanish once the Environmental Protection Agency finalizes its proposed carbon regulation, the center pole in the tent of the Obama administration’s climate action plan.

The Clean Power Plan aims to cut carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, the biggest source of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, by 30% by 2030 from 2005. There’s no chance of meeting that target—or the nation’s international carbon pledge—without reducing coal consumption.

So the rule, EIA noted drily in its outlook, would have “a material impact on projected level of coal-fired generation.”

Explaining the Coal Turmoil

The same glum message for coal comes through in all the EIA’s forecasts—whether for the short term or the long term.

This year, natural gas is expected to supply 30% of the nation’s electricity, up from 27% last year. At any time now, electricity produced from gas may surpass coal power—they are running neck and neck this year.

“EIA expects natural gas generation in April and May will almost reach the level of coal generation,” the agency said on May 12, “resulting in the closest convergence in generation shares between the two fuels since April 2012.”

U.S. coal production, as a result, is expected to fall by 7.1% in 2015. The amount of coal burned by electric plants will drop 6%. Already, unburned coal started to pile up at power plants this winter.

It’s not just natural gas that threatens coal, however, according to a recent breakdown of new generating capacity.

The amount of renewable energy capacity coming on-line almost equals the amount of coal capacity going off-line. New gas capacity has helped compensate by providing the same steady reliable power that coal provided while the wind and sunshine come and go.

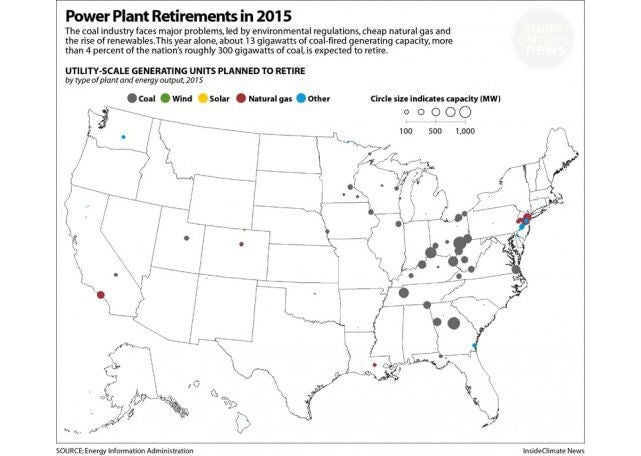

About 13 gigawatts of coal-fired generating capacity, more than 4% of the nation’s 300 or so gigawatts of coal, is expected to retire this year. New wind plants will add 10 gigawatts. Solar will add 2 gigawatts more. Gas will provide another 6 gigawatts. (A gigawatt of electricity can power at least half a million homes.)

If electricity demand picks up next year, so will the use of coal—but not by as much as might be expected.

The coal plants that are shutting down are relatively small, old and inefficient. The plants that would ramp up to meet any new demand for power would be bigger, more modern and more efficient—and they would need less coal to make the same amount of electricity.

The retirements of coal plants that are currently washing over the industry were brought on by a rule that sets new mercury and air toxic standards—the MATS rule, which has just taken effect. (It has been challenged in the Supreme Court, which will rule shortly.)

The combination of the MATS rule and the competition from gas and renewables will lead utilities to shut down 31 gigawatts of coal fired boilers between 2014 and 2016, EIA has projected. Another 4 gigawatts would shift from coal to natural gas.

The Government Accountability Office, in a separate estimate last year, said that between 2012 and 2025 total retirements would amount to 42 gigawatts—that’s 13% of total electric capacity nationwide. The plants that are shutting down, it said, are concentrated in four states: Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky and West Virginia.

Downgraded to Negative

To the extent that new power plant capacity is coming on line—and that is not expected to happen as fast as it used to—new coal plants are not in the picture.

Plainly, this means that a lot of the money that consumers spend on electric bills will ultimately go to gas producers, not coal producers.

In 2040, 55% of the money utilities spend on fuel will go to natural gas companies, and only 35% to coal companies. In recent years, the two have been running neck and neck.

Coal’s financiers are taking note.

In March, the Moody’s debt rating service downgraded the outlook for North American coal to negative, predicting that earnings would “drop 6% to 8% over the next year or so.”

Peabody Energy, by far the biggest U.S. producer, said in its latest quarterly earnings statement that after watching power companies’ consumption wither in the first quarter, it had cut its own forecasts for U.S. demand, which it now sees dropping by up to 100 million tons this year. The fall-off in production would continue in the second half of this year, it said.

This month, Bank of America said it would be cutting back on lending to the industry. Its stance was aimed at confronting climate change and recognized the risks of lending to an industry whose assets might be stranded.

The decline in coal’s fortunes has been welcomed by environmentalist campaigners, although they say it’s not happening fast enough to keep the world within its carbon budget. At current rates of fossil fuel-burning, the world will exceed within a few decades the emissions limit that might keep the planet within the 2 degrees Celsius safe threshold this century. To hit that target, emissions of carbon dioxide from the energy sector have to decline rapidly, and eventually reach zero.

As negotiations continue toward a possible climate treaty in Paris later this year, the U.S. has said it will cut emissions 26%-28% below 2005 levels by 2025. That would require doubling its average recent pace of reductions, from 1.2% per year on average during the 2005-2020 period to 2.3%-2.8% per year on average between 2020 and 2025.

Because it omits the influence of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan from its forecasts, the EIA projections don’t show any drop in US greenhouse gas emissions.

Instead, its business-as-usual outlook shows that emissions—which had been on a downward path since 2005, and then rose a bit—will go up gently in the next couple of years, then drift along a long, steady horizontal path.

That shouldn’t be too surprising. Until there are strong new policies in place to restrain the burning of fossil fuels, it’s unlikely that the market’s invisible hand will get the desired results.