Campaign politics made the US vice presidency a very weird job

Hillary Clinton is likely to select secretary of housing and urban development (HUD) and former mayor of San Antonio, Texas, Julián Castro as her running mate, should she secure the Democratic nomination for president in 2016. This, according to a number of commentators in Washington, including former HUD secretary Henry Cisneros, is yet another “inevitability” tacked to Clinton’s candidacy. Cisneros told Univision on May 17:

Hillary Clinton is likely to select secretary of housing and urban development (HUD) and former mayor of San Antonio, Texas, Julián Castro as her running mate, should she secure the Democratic nomination for president in 2016. This, according to a number of commentators in Washington, including former HUD secretary Henry Cisneros, is yet another “inevitability” tacked to Clinton’s candidacy. Cisneros told Univision on May 17:

“What I am hearing in Washington, including from people in Hillary Clinton’s campaign, is that the first person on their lists is Julián Castro… They don’t have a second option, because he is the superior candidate considering his record, personality, demeanor, and Latin heritage.”

When it comes to electoral politics in 2015, “Latino heritage” is nothing to trifle with. (Castro is Mexican American.) The Democratic party has notably fewer nationally electable, big-name Latino candidates than the Republicans do; and the Clinton campaign’s idea is likely to neutralize any history-making novelty a potential Marco Rubio-led GOP ticket might capitalize on. (Ted Cruz’s anti-immigration politics will render him a complete nonstarter among Latinos.) In these ways, hitching Castro to the “inevitable” Clinton Democratic nomination makes a lot of sense.

Still, others say, electability and charisma aside, Castro lacks the experience to be “one heartbeat away” from the Oval Office. (Or “one funny looking mole,” as Tina Fey put it.) His tenure as mayor of San Antonio may have been more flash than substance; HUD is a bloated, ineffective federal agency that doesn’t take any particular skill to lead, etc., etc., ad nauseam.

It’s the kind of agenda-driven vetting skepticism we can expect for any presidential or VP candidate, regardless of party affiliation. But it does pose some interesting questions about how and why our candidates select “the second-most powerful person in the free world.”

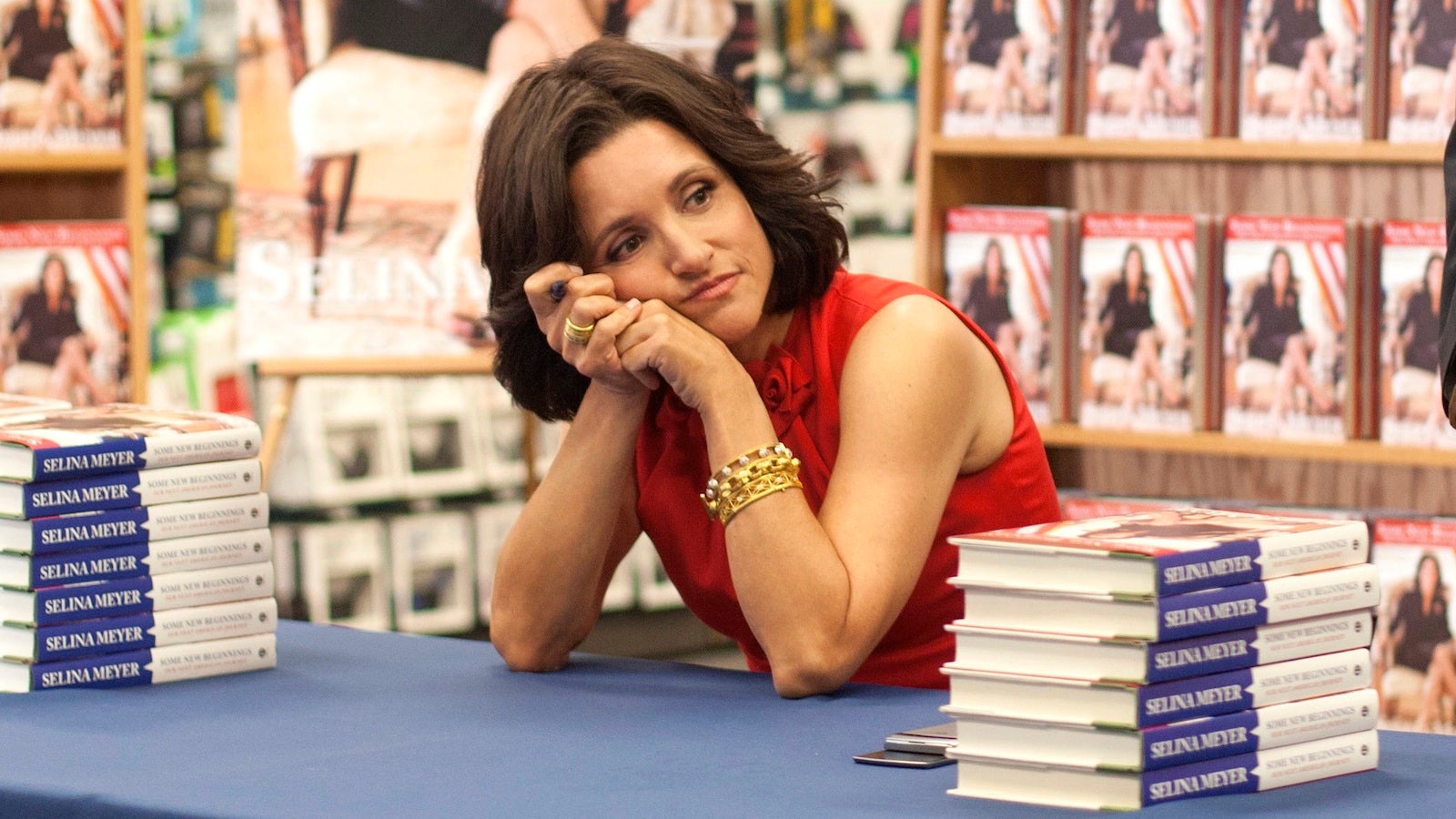

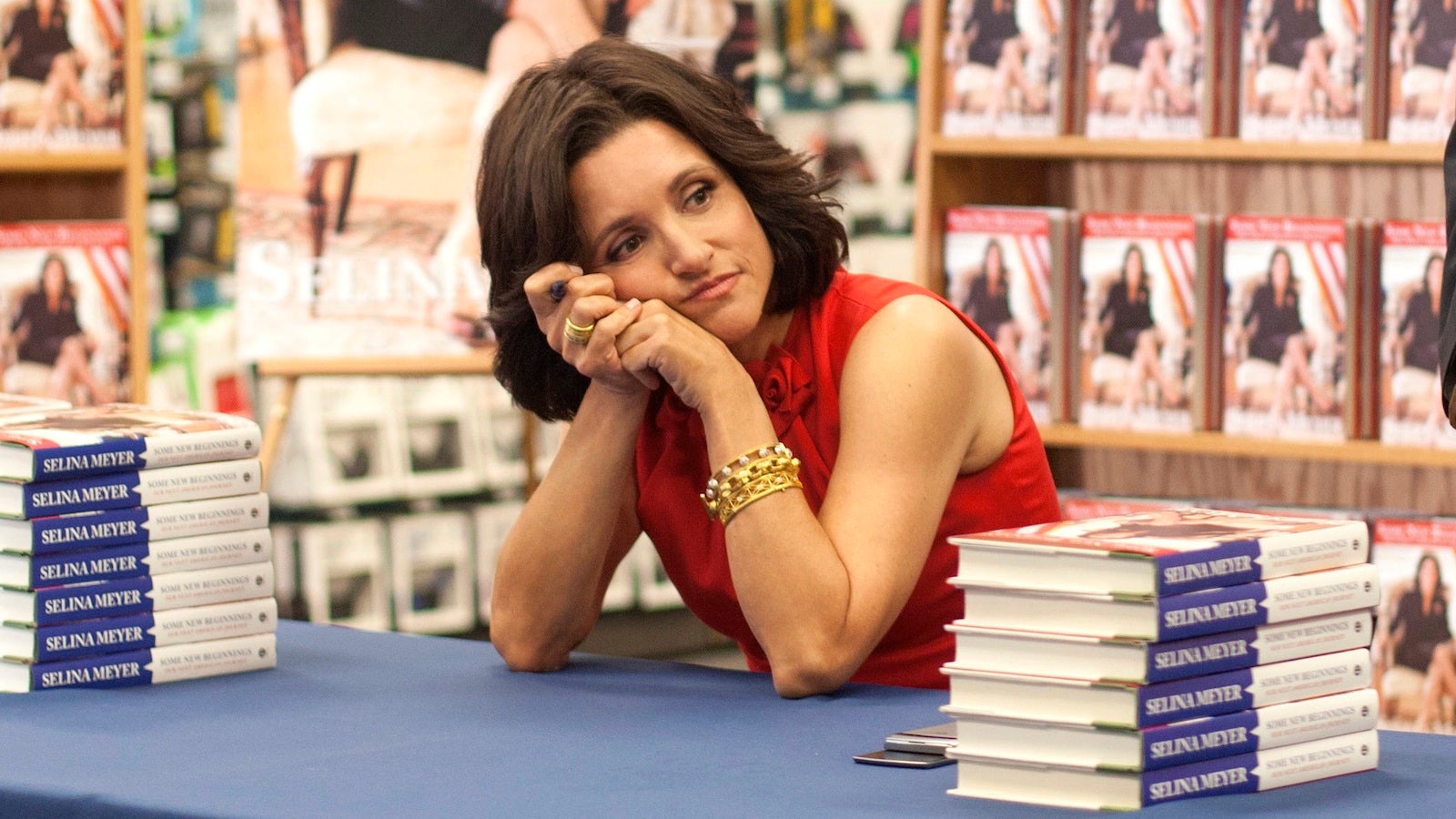

The office of vice president is weird. There’s no better way to put it. HBO’s Veep is pretty spot-on in its depiction—a frustrating mix of bureaucratic nonsense and clownish ribbon-cutting, all within tantalizingly close reach of the most influential job on earth. Which is perhaps how campaigns have justified the evolution of vice presidential selections from the pragmatic to the ideological (bordering on the theatrical).

Ticket-balancing has always been a thing. But the reasons for it have changed. East Coast-establishment Dwight D. Eisenhower picked West Coast-establishment Richard Nixon to bridge the cultural divide between east and west, old and new in a country gripped by population boom. New Englander John F. Kennedy picked Texan Lyndon B. Johnson to mesh Yankee Democrats with their Southern counterparts.

Though they weren’t universally appreciated choices, they were practical ones: Nixon was a senator from California, Johnson was a senator from Texas (and senate majority whip). In the decades since, ticket-balancing has taken an ideological turn; candidates at the extremes picking moderate running mates, and vice versa. So far, it hasn’t worked: Michael Dukakis selected the more moderate Lloyd Bentsen; a center-right John McCain picked Tea Party darling Sarah Palin (also an attempt to court spillover from Hillary’s disappointed 2008 supporters). Mitt Romney appealed to the Libertarian element in the GOP by selecting congressman Paul Ryan.

This perhaps makes the case for a return to roots—running mates with broad leadership experience and a record of success; beloved by large swathes of the country. After all, an inexperienced, yet shiny and ideologically appropriate running mate has yet to secure an election for an otherwise wobbly candidate. (In Quayle vs. Bentsen, someone had to come out on top.) It remains to be seen just how wobbly Hillary’s candidacy could be—if at all—or whether the selection of a greenhorn running mate could damage such a strong personal brand.

In any case, the selection of ideologically representative VPs over experienced politicos with geographical clout might explain why the office is viewed with decreasing esteem each election cycle.

But distilling the problem of ideologue running mates down to degrees of experience is an oversimplification. The saga of Dan Quayle aside, recent history indicates that, when a running-mate selection becomes a campaign’s Achilles’ heel, it has less to do with experience or qualifications than general buffoonery. Julián Castro is no Richard Nixon or Lyndon B. Johnson; but neither is he a winking Sarah Palin, a helmet-haired John Edwards, or even a John “I may have inspired the Civil War” Calhoun. If Castro is truly Clinton’s pick, all he has to do is steer clear of biker diners.

The bar, in other words, isn’t set very high.