Scientists just realized a chunk of Antarctica is leaking trillions of liters of water into the sea

Things have been getting slushy on the bottom of the planet. But not the Southern Antarctic Peninsula, that tongue of ice and land that flicks up toward Chile. Or at least, that’s what scientists had thought.

Things have been getting slushy on the bottom of the planet. But not the Southern Antarctic Peninsula, that tongue of ice and land that flicks up toward Chile. Or at least, that’s what scientists had thought.

New research, however, reveals that in the last five years, the peninsula has been melting at a rapid clip, sending 300 trillion liters of melted glacier into the ocean—what you’d get if you filled the Empire State Building with water and dumped it into the sea 350,000 times. That rate shows no sign of slowing.

That’s according to a team from the University of Bristol that just published its findings in Science (paywall). Using satellite measurements to analyze changes in ice-sheet elevation, they discovered that glaciers that had previously been stable had been shrinking by as much as four meters (13 feet) a year. In fact, the Southern Antarctic Peninsula has been shedding ice so swiftly that it’s altered the Earth’s gravity field, they found.

What’s behind the alarming change?

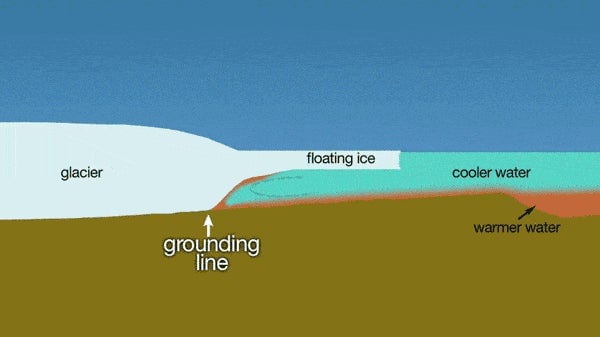

Hot water, probably. The shifting of wind patterns around Antarctica due to climate change and ozone depletion now whip warmer currents up from the ocean’s depths. Balmy seas lap the underside of glaciers the way you might eat a popsicle, steadily melting the ice.

Here’s what this looks like:

At the same time, most of the land of the peninsula is already below sea level—which means the ice shelf on top of it is too. Worse, in many places, the further inland you go, the more that bedrock slopes downward. That makes it easier for the sea to push the “grounding line”—the place where the ice shelf meets the land—further back.

This structural situation obviously isn’t new. For eons, scientists have understood the region to be much stabler than other regions of Antarctica—which is ironically why it’s been overlooked for so long, says Bert Wouters, a fellow at the University of Bristol who led the study, in a press release. What likely triggered rapid melting starting in 2009 is that the subsurface melting passed a critical threshold. More research is needed to tell how much longer the thinning process will continue, he says.

That said, the process that started in 2009 builds on itself. The glaciers on the edges of ice shelves act as a buttress to the ice further inland, preventing it from slumping into the sea. As the grounding line retreats, it exposes more and more of the glacier to warm water. That thinning, in turn, weakens the force preventing the rest of the glacier from flowing ocean-ward. The downward-sloping bedrock helps accelerate this all the more.