We can overcome our biases, racial and otherwise, by first becoming aware of them

This piece is part of “From Moment to Movement,” a conversation and essay series on race and policy in America in collaboration with Howard University.

This piece is part of “From Moment to Movement,” a conversation and essay series on race and policy in America in collaboration with Howard University.

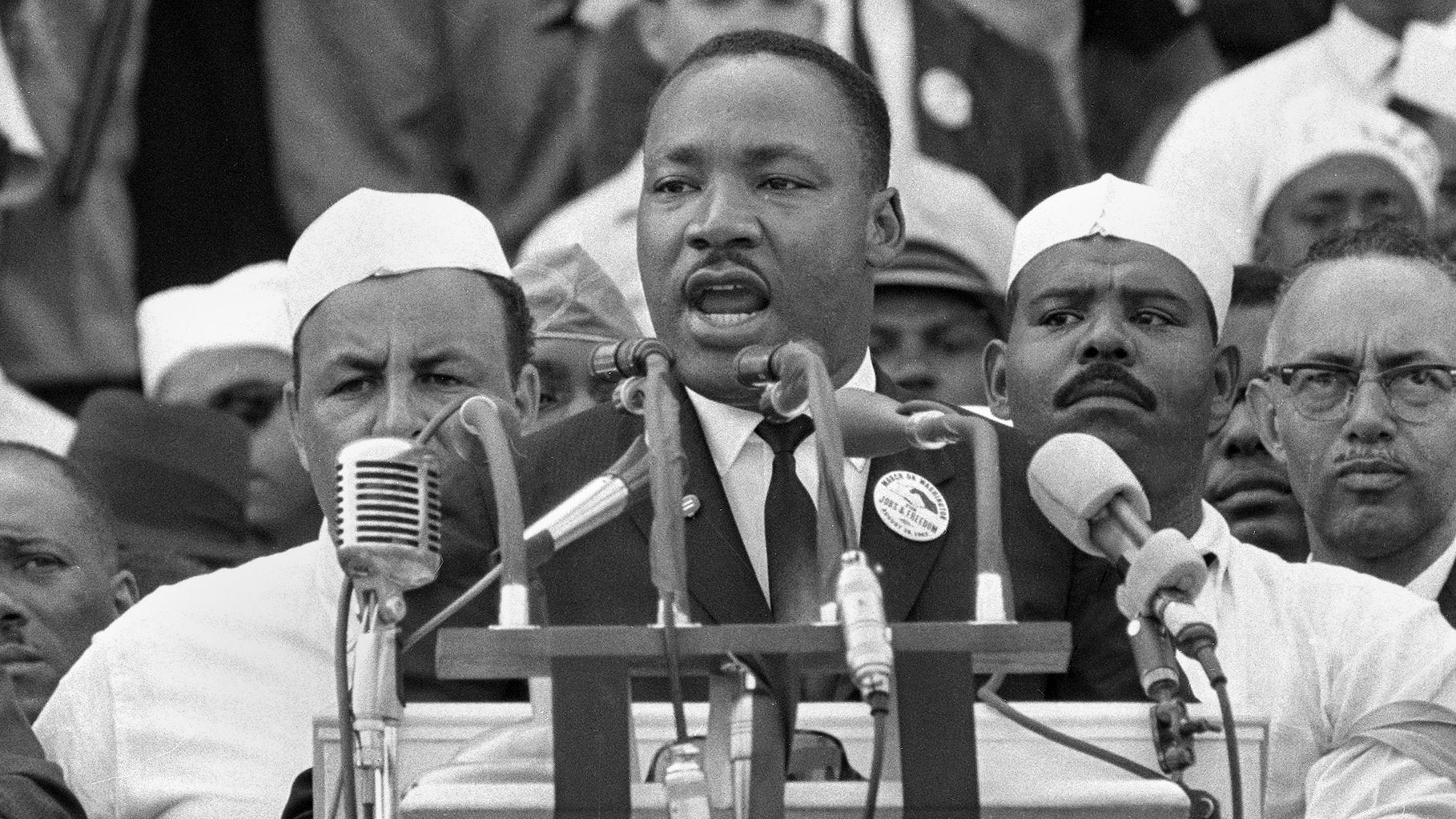

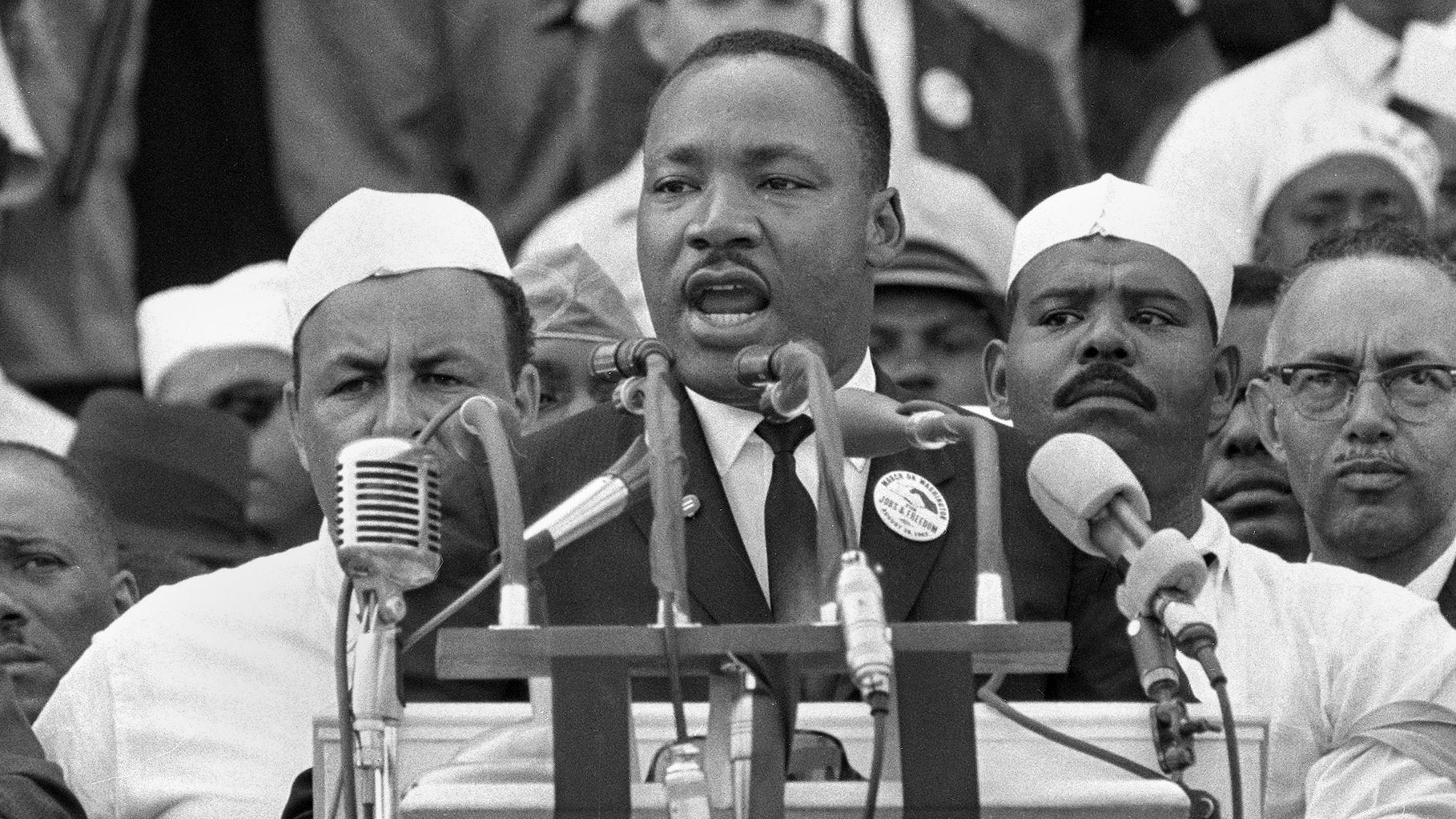

In many ways, our world has transformed—culturally and politically—since Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963. In one big way, it has stayed largely the same: Despite the fact that we have an African American president, the biased and negative perception of the black man is no different today than it was prior to the Civil Rights Movement. And it’s this enduring perception that is, once again, at the root of our contemporary civil rights moment.

How do we change perceptions?

That’s a question that we’ve been trying to answer for decades. But as we shift from moment to movement and identify the key parts of the post-Ferguson agenda, we’d be wise to remember that change requires shifting both policy and culture. It requires tackling both external problems—such as bias-based policing and discriminatory policies in the criminal injustice system—and internal ones, too. The internal problems are trickier, because they require a self-diagnosis of the biases we harbor within our subconscious minds—the perceptions that we act upon, with or without being aware of them.

To move forward, all of us need to do the hard work of self-reflection.

In other words, while the government has the responsibility to ensure that policies are in place to protect people from racial bias, policies alone cannot fix the problem. To move forward, all of us need to do the hard work of self-reflection.

It may help, first, to understand more about the origins of these biased perceptions. The ones I’m talking about are based on the insidious stereotypes of black Americans that link blackness with crime. Kathryn Russell-Brown, a professor of law and director of the Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations at the University of Florida, calls this the “CriminalBlackMan” stereotype—the notion that, in America’s collective consciousness, black masculinity and criminality are inextricably linked.

In today’s society, perceptions like these are rarely openly discussed. Instead, they are maintained through implicit bias—the often subliminal thinking that can influence partial-policing decisions and covert racist practices—in all of their subtle or veiled ways of operating. An officer who has implicit biases may rationalize a decision based on a logical sequence of events, and not even realize that her decision has been informed by negative perceptions. But if she has even vaguely negative perceptions of a particular group, that can substantially impact how she interacts with its members. This is particularly true during high-stress situations that require split second decision-making, forcing an officer to rely on instinct. She may, for example, be more inclined to draw her weapon quickly when interacting with a black person than a white person, because she considers black people to be more dangerous.

But wait, you may be thinking. I’m not racist or biased—surely the problem is with those police officers. Yet, it is difficult to grow up in American society without accumulating biases along the way, as there are subtle messages embedded in the fabric of American culture. The lessons we were taught as children about different racial/ethnic groups, gender differences, and sexual orientation shape our perceptions of others. These symbols are displayed in various forms, including the use of images, and the use of language describing ”good” and “bad” in this society. Think for a moment about all the ways in which we deploy associations with sexual orientation, gender, and race in everyday language. Common sayings like “that’s queer,” “don’t act like a girl,” and the use of the term “black” to denote something negative—such as blackmail and blackball—engender negative views and perceptions.

Diving a bit deeper, there’s also something called “aversive racism,” which happens when people avoid interacting with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Here, like with covert racism, people may claim to be egalitarian, yet respond in biased ways against members of a group.

Today, we’re more likely to see covert and aversive displays of bias—which are, by their nature, harder to see, and thus address. Jennifer Eberhardt, an associate professor of psychology at Stanford University, has been examining the effects of subtle racial bias, and is currently working with police departments to “reduce unconscious bias” and end racial profiling. Part of her research points to one of the trickiest parts of tracking covert and aversive displays of bias: most people don’t think they’re perpetrators. White Americans typically believe that they don’t hold biased views about other races; she has found that isn’t the case—biases inform our thinking more than we might expect. More specifically, in experiments with police officers and students, she found that both groups have “implicit biases” against African Americans. So while the spotlight is rightfully on law enforcement, this is also an opportunity for all of us to cross-check the lens through which we see each other.

So the question is, how do we overcome our biases?

At the micro-level, one of the most effective answers is also one of the simplest. We can start to overcome our biases once we become aware of them. In a study on racial bias among NBA referees, a group of researchers with the National Bureau of Economic Research found racial bias influenced fouls called by the referees. This study received a blitz of media attention, and in a follow-up study the researchers discovered no racial bias in the practice of calling fouls. That suggests that bringing the issue to light can positively reduce racial bias in decision-making practices.

Beyond a big media campaign, awareness can often begin through dialogue…

But how do we become aware, exactly?

Beyond a big media campaign, awareness can often begin through dialogue—which was the idea behind president Clinton’s Presidential Initiative on Race. It was an effort to both study and convene conversations around the country on race and racism. Unfortunately, other issues that dominated the media of the day dwarfed the initiative.

It’s time to seize this moment in history, and restart those conversations to bridge the divide between policy and practice. We need another Presidential Initiative on Race—or something like it—to help keep these issues in the forefront of public discourse.

And we must keep those issues at the forefront of our own minds, by interacting with others who are different than us. A few years ago, I had an experience that helped me see my own biases and the importance of having an open mind. While working on a project, I developed a friendship with someone who happened to be of a different race. One day while we were chatting in his office he pulled out an autographed picture of Ronald Reagan, and said he would post the picture, but people at work were way too liberal. I thought he was kidding at first, but soon discovered that he was a serious Republican, and I am a serious Democrat. If we had not already developed a friendship, I may have completely put up my guard if I was aware of our political differences. But the pre-established friendship allowed us to have those tough conversations about ideological differences with mutual respect.

We don’t all need to be friends. But if we want to get closer to the American ideal of equality, we must be open to identifying our individual biases, and becoming aware of how they impact our interactions and decisions.

It is only then that we can reach what Martin Luther King Jr. so eloquently stated about his dreams for his descendants—that they “will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

This article appeared in The Weekly Wonk, New America’s weekly e-magazine.