Everything about the world’s largest science experiment—as explained by the scientists themselves

Earlier this year, the world’s largest science experiment restarted after a two-year break. After an infrastructure upgrade, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland was expected to produce a lot more energy when smashing particles. After two months, it has achieved that feat by nearly doubling the previous energy record, colliding protons to produce 13 teraelectronvolts (TeV) of energy.

Earlier this year, the world’s largest science experiment restarted after a two-year break. After an infrastructure upgrade, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland was expected to produce a lot more energy when smashing particles. After two months, it has achieved that feat by nearly doubling the previous energy record, colliding protons to produce 13 teraelectronvolts (TeV) of energy.

On May 28, its scientists took to Reddit to answer questions about the new record—”ask us anything about what’s in store at this new energy frontier,” they wrote. Below are some of the best exchanges, condensed and edited for clarity.

Why are you doing this and what makes it important? What could you do with this data in the future?

In 1800, the study of electricity and magnetism were considered a theoretical study with no practical use. But once understood by means of theory and later experiments, it shaped the modern world.

The research we are carrying out at CERN may seem far from everyday life today. However, it will bring forward our knowledge of the natural world and it has already some practical spin-offs. For instance, accelerator technology is used for inoperable cancer surgery and the software protocol that powers the internet was invented at CERN.

How powerful are typical collisions and how powerful is 13 TeV really?

Clap your hands together. Congratulations, you’ve made a collision with more energy than the LHC. The difference is in the energy density. Stick a thumbtack against one of your palms, and clap again. Notice the difference?

By concentrating the collision point, even with the same total energy we get a more intense collision. Protons are very tiny, so when they collide the energy density is huge, making the results a lot more interesting than a hand clap.

How do the collisions create new particles?

The things being collided have stored in them enough energy to recreate conditions closer to the beginning of the universe when some particles roamed around freely. As the universe cooled down, those particles decayed into other particles, and so on. So the particles are new in the sense that they are being created now. But they are not new, in the sense that the same kind of particles existed close to the beginning of the universe.

How often are the 13 TeV collisions occurring? How much data does that generate?

There are 40 million collisions occurring every second. And we run typically eight months in the year and during that time collisions occur about 30% of the time. We actually only save about 1,000 of the 40 million events occurring each second, the 1,000 most interesting ones.

Indeed, the total storage we have worldwide for the data is about 50PB (which is 50,000,000GB). It is distributed over more than 100 computing centers, the biggest one at CERN. A single event is about 1.5MB in storage size.

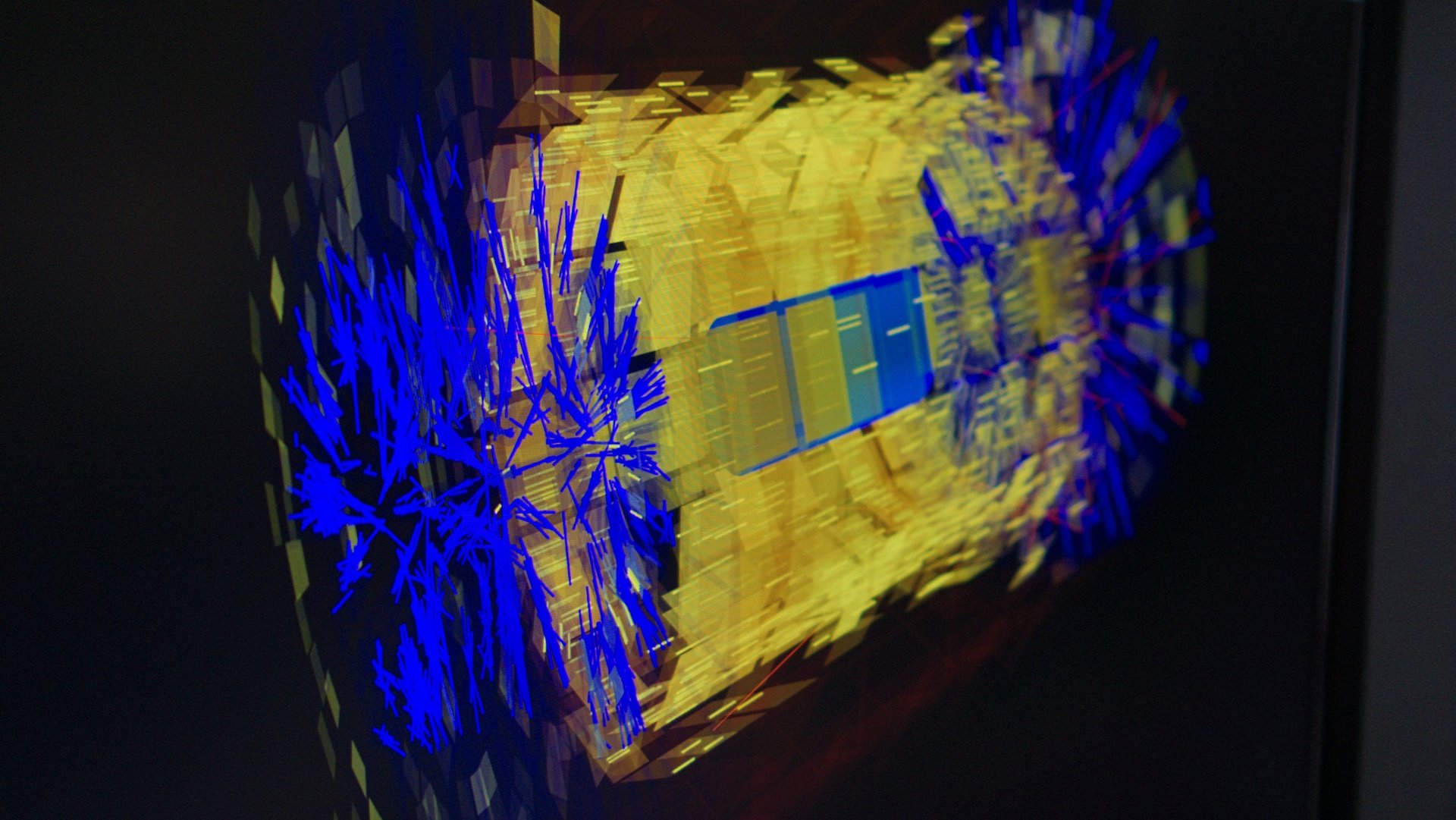

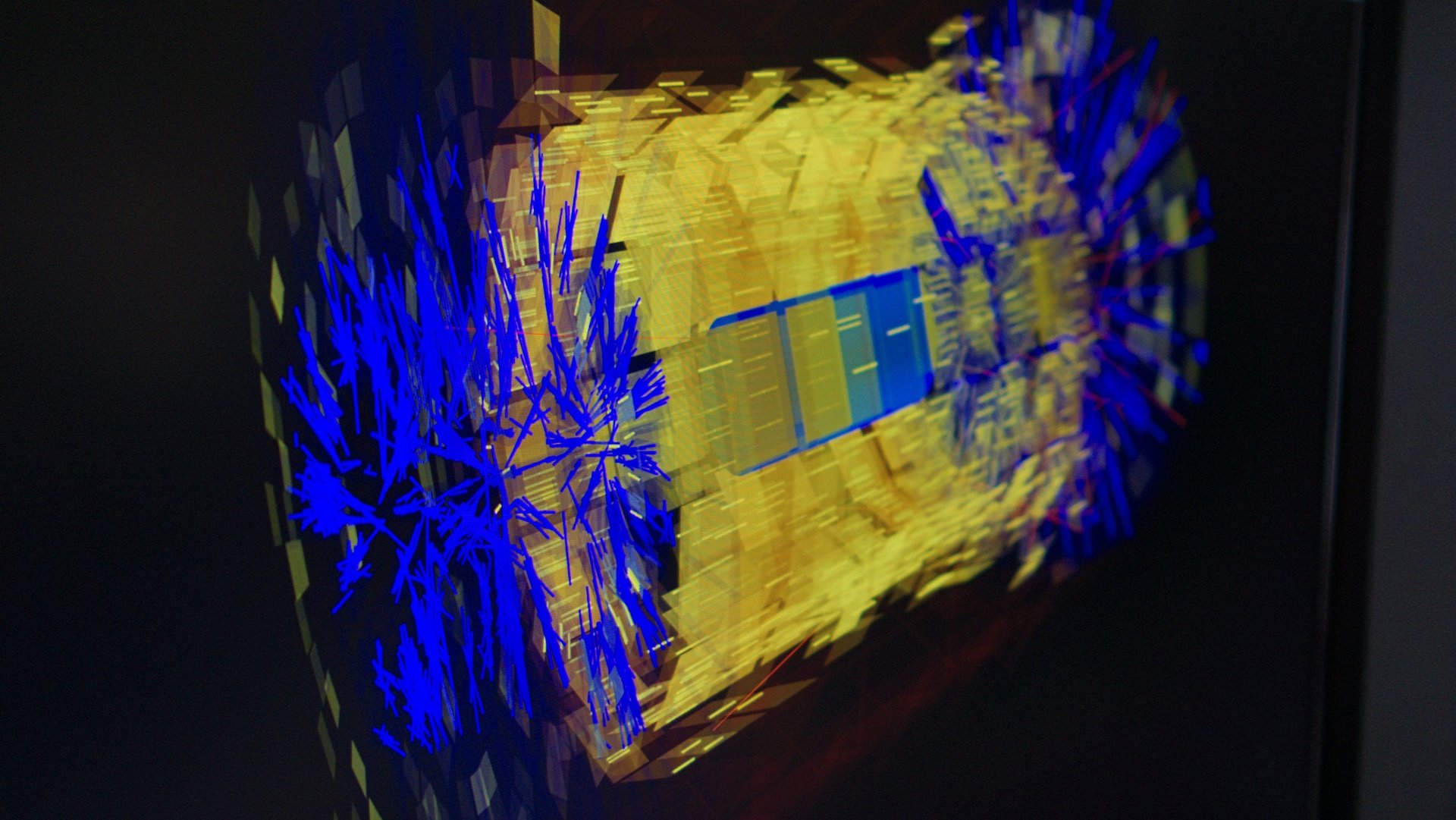

If the LHC was transparent, what would we see when the collisions occur?

You cannot see collisions with naked eyes. We need detectors to record the product of the elementary interactions and powerful computer to reconstruct the traces that these particles leave into them such as tracks of energy depositions.

What is the biggest enigma in particle physics that you guys want to find answers for in your lifetime?

What is dark matter is made of? We know it’s there but have never been able to produce or detect it on earth. It is rather embarrassing that we only understand 4% of our universe at the moment.