How Joe Biden learned to work with Jesse Helms, who should’ve been his nemesis

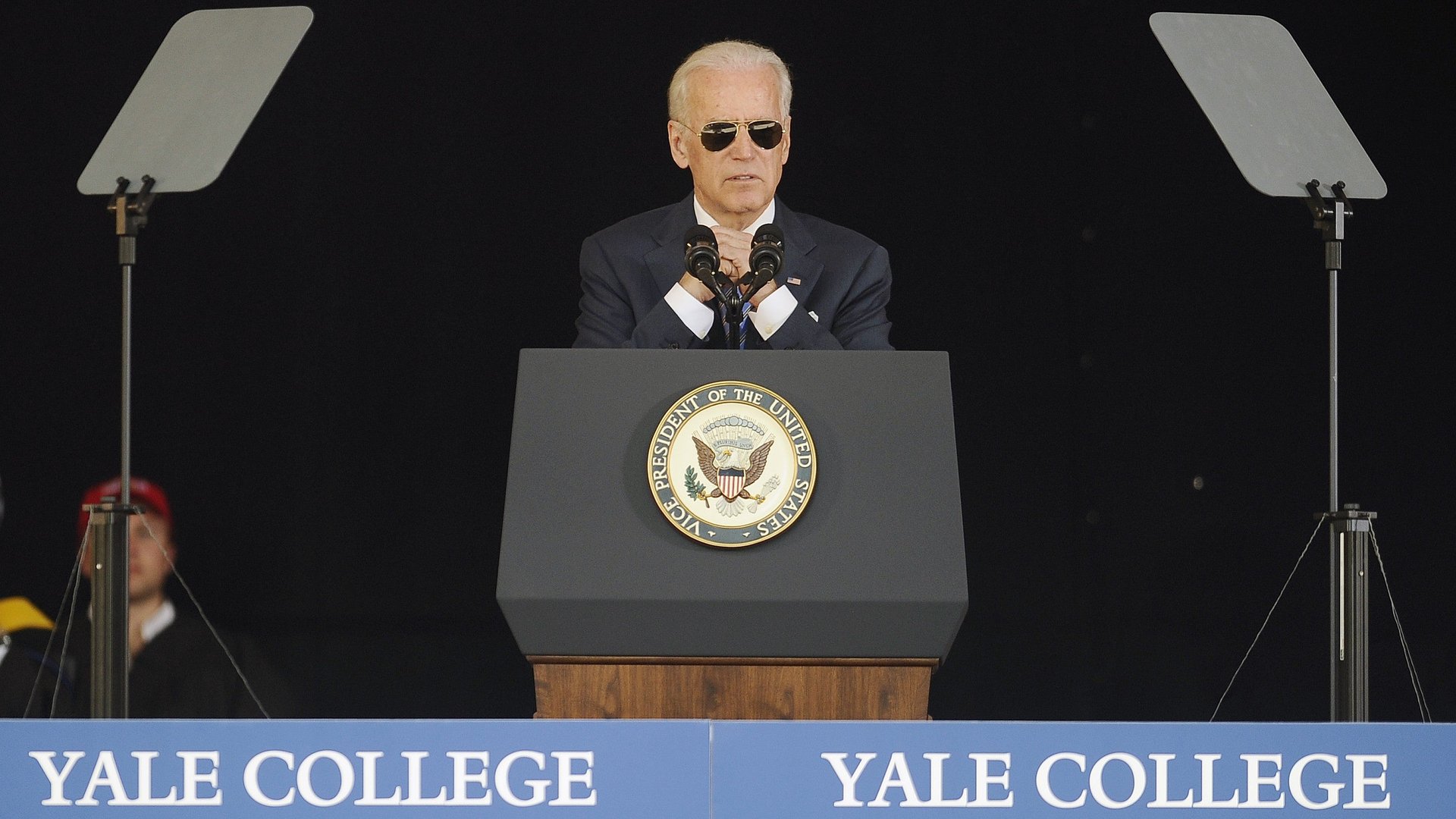

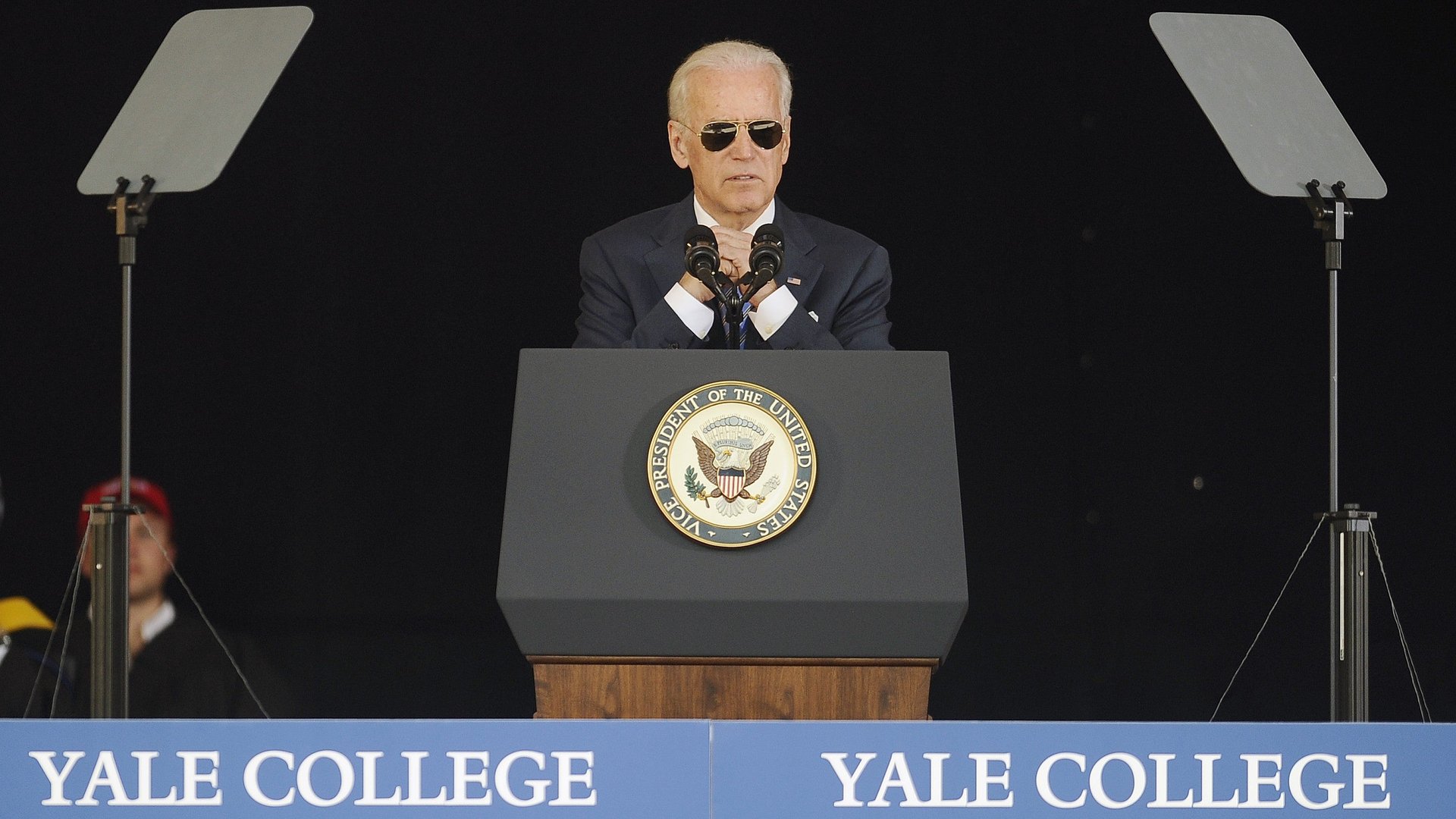

This May 17, vice-president Joe Biden address the graduates of Yale University at their Class Day. He spoke about the personal tragedies in his life, losing his wife and daughter to a car accident at age 30, which has been covered following the news of his son Beau’s death less than two weeks later. Beau and his brother survived the crash, and Biden almost resigned his newly won Senate seat before being talked out of it by Ted Kennedy, among others. Biden instead turned into an Amtrak commuter, coming home from Washington to Delaware every night to care for his sons as they recovered, and then to raise a family with his new wife, Jill.

This May 17, vice-president Joe Biden address the graduates of Yale University at their Class Day. He spoke about the personal tragedies in his life, losing his wife and daughter to a car accident at age 30, which has been covered following the news of his son Beau’s death less than two weeks later. Beau and his brother survived the crash, and Biden almost resigned his newly won Senate seat before being talked out of it by Ted Kennedy, among others. Biden instead turned into an Amtrak commuter, coming home from Washington to Delaware every night to care for his sons as they recovered, and then to raise a family with his new wife, Jill.

But Biden also spoke about how he learned to work with someone who should have been his nemesis, the conservative senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina. The full transcript of Biden’s speech is here, but below is his story about Helms:

I’ve met an awful lot of people in my career. And I’ve noticed one thing, those who are the most successful and the happiest — whether they’re working on Wall Street or Main Street, as a doctor or nurse, or as a lawyer, or a social worker, I’ve made certain basic observation about the ones who from my observation wherever they were in the world were able to find that sweet spot between success and happiness. Those who balance life and career, who find purpose and fulfillment, and where ambition leads them.

There’s no silver bullet, no single formula, no reductive list. But they all seem to understand that happiness and success result from an accumulation of thousands of little things built on character, all of which have certain common features in my observation.

First, the most successful and happiest people I’ve known understand that a good life at its core is about being personal. It’s about being engaged. It’s about being there for a friend or a colleague when they’re injured or in an accident, remembering the birthdays, congratulating them on their marriage, celebrating the birth of their child. It’s about being available to them when they’re going through personal loss. It’s about loving someone more than yourself, as one of your speakers have already mentioned. It all seems to get down to being personal.

That’s the stuff that fosters relationships. It’s the only way to breed trust in everything you do in your life.

Let me give you an example. After only four months in the United States Senate, as a 30-year-old kid, I was walking through the Senate floor to go to a meeting with Majority Leader Mike Mansfield. And I witnessed another newly elected senator, the extremely conservative Jesse Helms, excoriating Ted Kennedy and Bob Dole for promoting the precursor of the Americans with Disabilities Act. But I had to see the Leader, so I kept walking.

When I walked into Mansfield’s office, I must have looked as angry as I was. He was in his late ‘70s, lived to be 100. And he looked at me, he said, what’s bothering you, Joe?

I said, that guy, Helms, he has no social redeeming value. He doesn’t care — I really mean it — I was angry. He doesn’t care about people in need. He has a disregard for the disabled.

Majority Leader Mansfield then proceeded to tell me that three years earlier, Jesse and Dot Helms, sitting in their living room in early December before Christmas, reading an ad in the Raleigh Observer, the picture of a young man, 14-years-old with braces on his legs up to both hips, saying, all I want is someone to love me and adopt me. He looked at me and he said, and they adopted him, Joe.

I felt like a fool. He then went on to say, Joe, it’s always appropriate to question another man’s judgment, but never appropriate to question his motives because you simply don’t know his motives.

It happened early in my career fortunately. From that moment on, I tried to look past the caricatures of my colleagues and try to see the whole person. Never once have I questioned another man’s or woman’s motive. And something started to change. If you notice, every time there’s a crisis in the Congress the last eight years, I get sent to the Hill to deal with it. It’s because every one of those men and women up there — whether they like me or not — know that I don’t judge them for what I think they’re thinking.

Because when you question a man’s motive, when you say they’re acting out of greed, they’re in the pocket of an interest group, et cetera, it’s awful hard to reach consensus. It’s awful hard having to reach across the table and shake hands. No matter how bitterly you disagree, though, it is always possible if you question judgment and not motive.

Senator Helms and I continued to have profound political differences, but early on we both became the most powerful members of the Senate running the Foreign Relations Committee, as Chairmen and Ranking Members. But something happened, the mutual defensiveness began to dissipate. And as a result, we began to be able to work together in the interests of the country. And as Chairman and Ranking Member, we passed some of the most significant legislation passed in the last 40 years.

All of which he opposed — from paying tens of millions of dollars in arrearages to an institution, he despised, the United Nations — he was part of the so-called “black helicopter” crowd; to passing the chemical weapons treaty, constantly referring to, “we’ve never lost a war, and we’ve never won a treaty,” which he vehemently opposed. But we were able to do these things not because he changed his mind, but because in this new relationship to maintain it is required to play fair, to be straight. The cheap shots ended. And the chicanery to keep from having to being able to vote ended — even though he knew I had the votes.

After that, we went on as he began to look at the other side of things and do some great things together that he supported like PEPFAR -— which by the way, George W. Bush deserves an overwhelming amount of credit for, by the way, which provided treatment and prevention HIV/AIDS in Africa and around the world, literally saving millions of lives.

So one piece of advice is try to look beyond the caricature of the person with whom you have to work. Resist the temptation to ascribe motive, because you really don’t know -— and it gets in the way of being able to reach a consensus on things that matter to you and to many other people.

Resist the temptation of your generation to let “network” become a verb that saps the personal away, that blinds you to the person right in front of you, blinds you to their hopes, their fears, and their burdens.

Build real relationships -— even with people with whom you vehemently disagree. You’ll not only be happier. You will be more successful.

The second thing I’ve noticed is that although you know no one is better than you, every other person is equal to you and deserves to be treated with dignity and respect.

I’ve worked with eight Presidents, hundreds of Senators. I’ve met every major world leader literally in the last 40 years. And I’ve had scores of talented people work for me. And here’s what I’ve observed: Regardless of their academic or social backgrounds, those who had the most success and who were most respected and therefore able to get the most done were the ones who never confused academic credentials and societal sophistication with gravitas and judgment.

Don’t forget about what doesn’t come from this prestigious diploma — the heart to know what’s meaningful and what’s ephemeral; and the head to know the difference between knowledge and judgment.